WASHINGTON — President Biden, facing an intraparty battle over his domestic agenda, put his own $1 trillion infrastructure bill on hold on Friday, telling Democrats that a vote on the popular measure must wait until Democrats pass his far more ambitious social policy and climate change package.

In a closed-door meeting with Democrats on Capitol Hill, Mr. Biden told Democrats for the first time that keeping his two top legislative priorities together had become “just reality.” And he conceded that reaching a deal between the divided factions on his domestic agenda could take weeks.

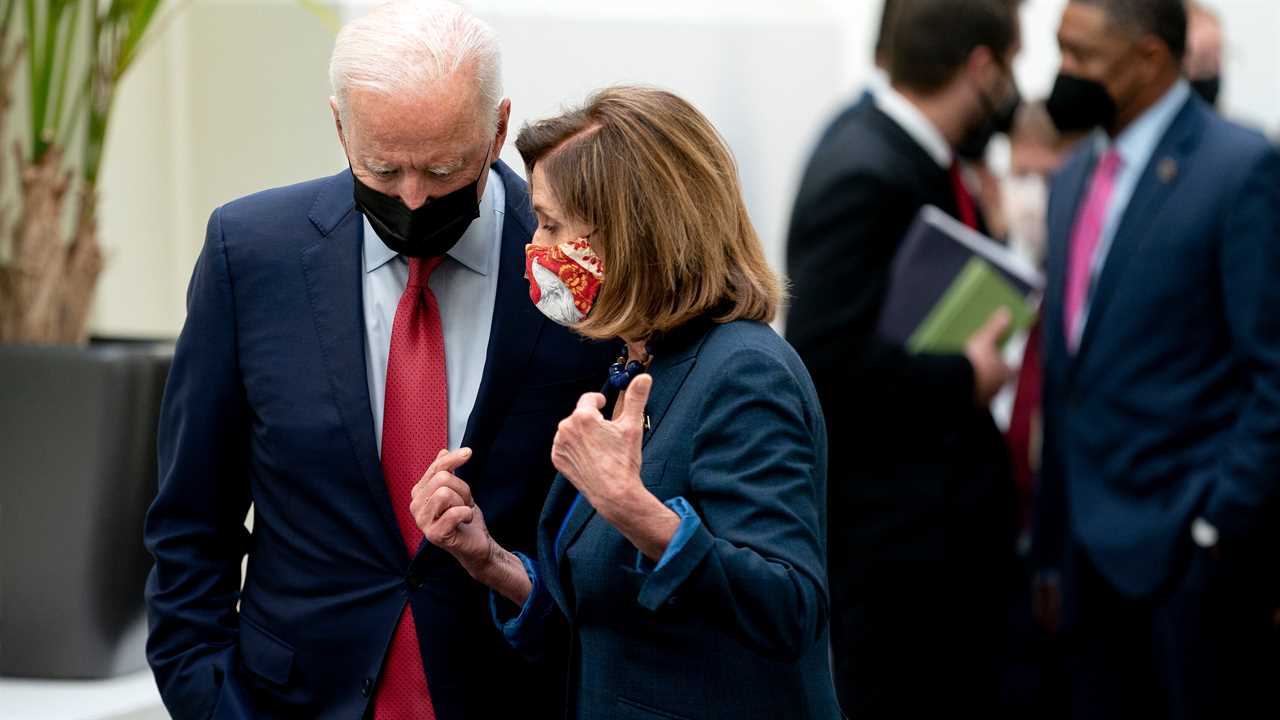

“I’m telling you, we’re going to get this done,” Mr. Biden told reporters Friday afternoon, appearing hand-in-hand with Speaker Nancy Pelosi after he left the closed-door gathering with Democrats. He added: “It doesn’t matter when. It doesn’t matter whether it’s in six minutes, six days or six weeks. We’re going to get it done.”

The decision was a blow to his party’s moderate wing, the driver behind efforts to separate the measures and score a quick victory on the traditional roads-and-bridges bill its members badly wanted to begin campaigning on. It was a win for the liberal flank, which has blocked any action on that bill until Senate Democrats unite around an expansive bill to confront climate change, expand the frayed social safety net and raise taxes on the rich.

And it amounted to something of a gamble, since the president was effectively delaying final action on the part of his economic agenda he has nearly secured in hopes of unifying his razor-thin Democratic majorities around the larger social policy and clean energy measures that have clearly divided them.

“If we get it done, it’ll be a victory. The question is: When do we get that victory?” asked Representative Henry Cuellar of Texas, one of nine centrist Democrats who extracted a promise from Ms. Pelosi for an infrastructure vote by October.

Democratic leaders insisted they had moved closer together and still had plenty of time to resolve their differences over the bigger bill and deliver on the president’s promises.

“While great progress has been made in the negotiations to develop a House, Senate and White House agreement on the Build Back Better Act, more time is needed,” Ms. Pelosi wrote in a letter to her colleagues. “Clearly, the bipartisan infrastructure bill will pass once we have agreement on the reconciliation bill.”

To buy negotiating space, House and Senate leaders planned to pass a stopgap measure to extend federal highway programs that expired after midnight on Friday.

Continuing talks between the White House and two holdout moderate senators, Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona and Joe Manchin III of West Virginia, centered on getting them to around $2 trillion in spending on climate change and social policies such as universal prekindergarten and paid family leave. But Ms. Sinema left Washington for a medical appointment and fund-raising retreat in Phoenix — complete with a morning donor hike and an evening cocktail hour and dinner — without a resolution.

Mr. Biden told Democrats in the private meeting that in his aides’ talks with the senators, they had discussed spending as much as $2.3 trillion. That is far below the $3.5 trillion the president has proposed. Still, he told the lawmakers that it would make a significant difference in Americans’ lives, accelerating economic growth, creating millions of good-paying jobs and delivering once-in-a-generation benefits to the middle class.

“You get a whole hell of a lot of things done,” Mr. Biden said, according to a person familiar with his remarks who relayed them on the condition of anonymity.

“I know a little bit about the legislative process,” Mr. Biden, a 36-year veteran of the Senate, also told the group. He said he could not recall a time when progress on “fundamental issues” had not required compromises.

His visit left a group of moderates who had been promised an infrastructure vote before October unsatisfied. Representative Abigail Spanberger, who narrowly won a Virginia district long dominated by Republicans, said that “success begets success,” and that a win on infrastructure would have propelled the president’s other priorities forward.

Politics Updates

- A stopgap bill could revive transportation programs and end furloughs caused by the voting delay.

- Biden tries to broker a deal among Democrats, with prodding and patience.

- Sinema, a holdout on the social spending bill, returns to Arizona for a doctor’s visit and a scheduled fund-raiser.

Supporters of the infrastructure measure, which overwhelmingly passed the Senate in August to bipartisan applause, were not shy about their disappointment.

“Respectfully, the president is wrong,” said Neil Bradley, executive vice president and chief policy officer for the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. “This bill should have been enacted six years ago. There was a chance to enact it six weeks ago. Delay has consequences, and none of them are good.”

But many Democrats shrugged off the criticism, saying the week’s chaos — including two postponed votes on the infrastructure bill, many closed-door meetings among feuding factions and much hand-wringing about the possible collapse of Mr. Biden’s agenda — would soon be forgotten.

“Everyone wants deals and promises to be kept, and their feelings are hurt when they feel like they’re not being treated right,” said Representative Tom Malinowski, Democrat of New Jersey, who wanted an infrastructure vote. But, he added, if Democrats ultimately deliver, “nobody back home gives a damn about any of that stuff.”

The infrastructure vote ultimately was tied to the social policy bill, whether Mr. Biden wanted that or not. White House officials and key centrist senators had tried all week to reach agreement on a less costly version that would rein in Democratic ambitions but persuade liberals to vote for the public works bill.

But the gap between the 10-year, $1.5 trillion spending limit demanded by Mr. Manchin and the policy demands of Democratic leaders and the White House proved too wide to bridge in a brief burst of negotiations. That meant the votes were not available in the House to pass an infrastructure bill that otherwise would clear Congress easily for a presidential signing celebration.

Mr. Biden did tell progressives to prepare to accept a significantly smaller social policy bill, after already coming down from $6 trillion in spending over 10 years to $3.5 trillion.

“It’s going to be tough — like, we’re going to have to come down on our number, and we’re going to have to do that work,” said the caucus leader, Representative Pramila Jayapal of Washington.

But liberals like Ms. Jayapal want to legislate with the sweep of the New Deal or the Great Society without the vast majorities that Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Lyndon B. Johnson enjoyed, Mr. Biden told them, according to Mr. Cuellar.

“What he was trying to do is tell the progressives, ‘Lower your expectations,’” he said.

Both Democratic factions feel somewhat betrayed by their leadership: the centrists who said this week that they would rather have seen their priority bill voted down than pulled from consideration and the liberals who were angry that the infrastructure bill came up before the Senate approved their priority bill.

The infrastructure measure, which would provide $550 billion in new funding, was supposed to burnish Mr. Biden’s bipartisan bona fides. It would devote $65 billion to expand high-speed internet access; $110 billion for roads, bridges and other projects; $25 billion for airports; and the most funding for Amtrak since the passenger rail service was founded in 1971. It would also accelerate a national shift toward electric vehicles with new charging stations and fortifications of the electricity grid that will be necessary to power those cars.

It is still unclear whether both bills, vital to Mr. Biden’s economic agenda, can get back on track. The break from negotiations could put more pressure on Mr. Manchin and Ms. Sinema to accept a larger social policy and climate package, and on the progressives to curb their ambitions.

Liberal lawmakers, who by and large come from safe Democratic districts, have the political luxury of holding firm, but they will now face the ire of Democrats in swing districts who gave their party its slender majorities in the House and Senate.

“Today’s delay, brought about by weeks of political posturing and gamesmanship, is incredibly disappointing,” Representative Chris Pappas of New Hampshire, one such Democrat, said in a statement late Thursday night. “The priorities in this legislation are common-sense solutions that will help connect our communities, create jobs and meet our state’s urgent and future needs.”

Before leaving Washington, the House and Senate hoped to extend federal authorization of surface transportation programs for 30 days. With the legislation delayed by deep disputes within the Democratic caucus, the new fiscal year began on Friday with those programs temporarily frozen and about 3,700 workers furloughed.

The bill would update and maintain the highway, transit and rail programs for five years, among other provisions. The Department of Transportation said that the administration was working to be able to swiftly reauthorize the frozen programs, and that payments to reimburse state and transit agencies for existing grants could allow work to continue uninterrupted.

Jim Tankersley, Madeleine Ngo, Catie Edmondson, Jonathan Martin and Luke Broadwater contributed reporting.