WASHINGTON — A bipartisan, $1 trillion infrastructure bill that is a pillar of President Biden’s agenda hung in the balance on Thursday night, as Democrats fought to corral the votes to pass legislation that had become mired in a broader internal battle over the party’s ambitions.

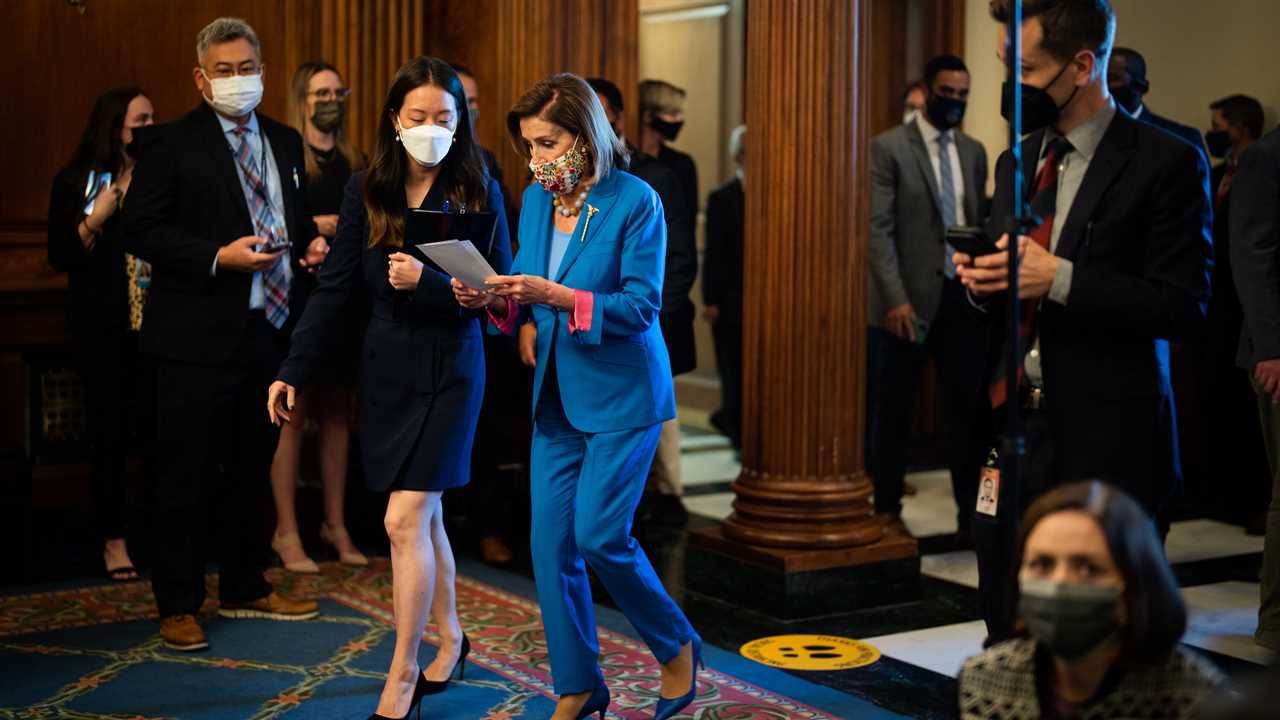

Speaker Nancy Pelosi and top members of Mr. Biden’s team worked into the evening at the Capitol in a frenzied effort to strike a deal between feuding factions and move forward on the expansive public works measure, which passed the Senate in August on a wave of bipartisan bonhomie.

Centrist Democrats and a handful of House Republican allies remained hopeful that the measure could squeak past a blockade of liberal Democrats, who have pledged to thwart its passage until the Senate approves a $3.5 trillion climate change and social safety net bill.

But the divide on that larger bill, between progressives and more conservative Democrats, appeared only to be growing wider and angrier.

The House and Senate did pass — and Mr. Biden signed — legislation to fund the government until Dec. 3, with more than $28 billion in disaster relief and $6.3 billion to help relocate refugees from Afghanistan. That at least averted the immediate fiscal threat of a government shutdown, clearing away one item on the Democrats’ must-do list, at least for two months.

But a planned Thursday vote on the infrastructure bill — a compromise plan that would invest heavily in the nation’s roads, bridges, highways and climate resiliency projects, delivering billions of dollars in projects to lawmakers’ states and districts — slipped into the night without the majority needed.

The measure, which would provide $550 billion in new infrastructure funding, was supposed to burnish Mr. Biden’s bipartisan bona fides. It would devote $65 billion to expand high-speed internet access; $110 billion for roads, bridges and other projects; $25 billion for airports; and the most funding for Amtrak since the passenger rail service was founded in 1971. It would also begin the shift toward electric vehicles with new charging stations and fortifications of the electricity grid that will be necessary to power those cars.

But progressive leaders were threatening to vote it down until they saw action on the legislation they really wanted — a far-reaching bill with paid family leave, universal prekindergarten, Medicare expansion and strong measures to combat climate change.

That ambitious plan was in peril on Thursday as conservative-leaning Democrats made it clear they could never support a package anywhere near as large as Mr. Biden had proposed. Senator Joe Manchin III of West Virginia told reporters that he wanted a bill that spent no more than $1.5 trillion, less than half the size of the package that Democrats envisioned in their budget blueprint.

And he had a blunt message for the House progressives. “I’ve never been a liberal in any way, shape or form,” he said. If they wanted their way, he advised, “elect more liberals.”

Representative Ilhan Omar of Minnesota, a leader of the House Progressive Caucus, fired back: “If the senator thinks electing more Democrats is how you get it done, then that is something he should say to the president, because this is the president’s agenda.”

Mr. Manchin spoke out about his position after a memo detailing it was published in Politico on Thursday.

The document was instructive in ways well beyond the spending total. His bottom-line demands included means-testing any new social programs to keep them targeted at the poor; a major initiative on the treatment of opioid addictions that have ravaged his state; control of shaping a clean energy provision that, by definition, was aimed at coal, a mainstay of West Virginia; and assurances that nothing in the bill would eliminate the production and burning of fossil fuels — a demand sure to enrage advocates of combating climate change.

On provisions to pay for the package, he was more in line with other Democrats, backing several rollbacks of the Trump-era tax cut of 2017, including raising the corporate tax rate to 25 percent, up from 21 percent; setting a top individual income tax rate of 39.6 percent, up from 37 percent; and increasing the capital gains tax rate to 28 percent, another substantial boost.

But that tax agreement ran counter to the position of the other Democratic holdout, Senator Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, who has told colleagues she opposes such significant tax rate increases.

As of Thursday evening, Ms. Pelosi was still pressing forward with a vote on the infrastructure bill, projecting relentless optimism as competing groups of liberal and moderate lawmakers shuttled in and out of her office.

“We’re on a path to win the vote — I don’t want to even consider any options other than that,” she declared at her weekly news conference.

Ms. Pelosi, 81, who wrangled the Affordable Care Act through the House 11 years ago, put her reputation as a legislative powerhouse on the line in the talks, saying she had told top Democrats that the social policy and climate measure was “the culmination of my career in Congress.”

As the sun set in Washington, Susan E. Rice, the director of the White House Domestic Policy Council, and Brian Deese, the director of the National Economic Council, were huddled in her office with her aides and with staff of the Senate majority leader, Chuck Schumer of New York, trying to hammer out a social policy framework that could satisfy the warring factions, according to an official.

Some Democrats saw Mr. Manchin’s memo as at least a starting point for negotiations that have foundered in the absence of a clear signal from him or Ms. Sinema about what they could accept.

Mr. Manchin said he had informed Mr. Biden of his top-line number in the last few days, about two months after he and Mr. Schumer both signed the memo acknowledging Mr. Manchin’s stance.

His comments on Thursday were his most forthcoming about what he wanted to see in the social policy plan, which Democrats hope to push through using a fast-track process known as budget reconciliation that shields fiscal legislation from a filibuster. Democrats are trying to pass the package over united Republican opposition, meaning they cannot spare even one vote in the evenly divided Senate.

Mr. Schumer, who signed the agreement as he was working to persuade Mr. Manchin to support the party’s budget blueprint, appeared to have scrawled, “I will try to dissuade Joe on many of these” underneath his signature.

On Thursday, a spokesman emphasized that Mr. Schumer did not consider it binding.

“As the document notes, Leader Schumer never agreed to any of the conditions Senator Manchin laid out; he merely acknowledged where Senator Manchin was on the subject at the time,” said Justin Goodman, the spokesman.

Also on Thursday, Ms. Sinema’s office said she would not “negotiate through the press” but had made her priorities and concerns known to Mr. Biden and Mr. Schumer.

But caught in the middle was the infrastructure bill, negotiated by Republican and Democratic senators, pushed hard by the nation’s largest business groups and backed widely in polls by voters of both parties.

Representative Tom Reed of New York, a moderate Republican who has long publicly supported the bill, said the handful of House Republicans backing the measure was growing, against the wishes of House G.O.P. leadership. If Ms. Pelosi could keep the vote close, he said, more Republicans would want to be on the winning side — with bragging rights on such a popular bill.

“We’re going to have the vote,” he said. “It’s going to be close, but I’ll tell you, there is a good chunk of Republican members that want to be a yes.”

Even on a day of uncertainty and intraparty squabbles, Democrats said the disarray surrounding the bill’s consideration would not take away from its chances of enactment.

“Somebody may see a story the next day that makes it seem as if we’re disorganized,” said Representative Tom Malinowski, Democrat of New Jersey and one of the centrists pressing for a quick vote. “It doesn’t matter two weeks later if I’m at the ribbon cutting for a Gateway Tunnel,” a huge new project connecting New Jersey to New York that is funded in the infrastructure bill.

That was echoed by Senator Bernie Sanders, independent of Vermont, who was standing by liberals holding out for as big a social policy bill as possible.

“If there’s no vote today, or it’s defeated, the world will not collapse,” he said. “This is a hugely consequential bill. We have time. Let’s do it right.”

But as the standoff persisted, the outlook for the measure remained unclear.

“Nobody should be surprised that we are where we are, because we’ve been telling you that for three and a half months,” said Representative Pramila Jayapal, Democrat of Washington and the head of the Congressional Progressive Caucus.

She then put out a fund-raising email boasting that “progressives are flexing our muscle on Capitol Hill.”

Representative Stephanie Murphy of Florida, a moderate who has pushed for a swift infrastructure vote, said if the House failed to approve a bill that passed the Senate with 69 votes — 19 of them Republican, including the minority leader, Mitch McConnell of Kentucky — it would send a damaging signal about Washington.

“It absolutely must pass because as Democrats and Republicans, we have to demonstrate to the American people that we can still govern in this very partisan time,” she said.

Lawmakers reached a deal on the spending legislation after Democrats agreed to strip out a provision that would have raised the federal debt limit through the end of 2022, averting a default otherwise projected for sometime next month.

Senate Republicans blocked an initial funding package on Monday because the debt ceiling increase was included, refusing to give the majority party any of the votes needed to move ahead on a bill to avoid a first-ever federal default in the coming weeks.

Madeleine Ngo, Luke Broadwater and Sheryl Gay Stolberg contributed reporting.