WASHINGTON — Americans who go into the military understand the loss of personal liberty. Many of their daily activities are prescribed, as are their hairstyles, attire and personal conduct.

So when it comes to taking a coronavirus vaccine, many troops — especially younger enlisted personnel as opposed to their officers — see a rare opportunity to exercise free will.

“The Army tells me what, how and when to do almost everything,” said Sgt. Tracey Carroll, who is based at Fort Sill, an Army post in Oklahoma. “They finally asked me to do something and I actually have a choice, so I said no.”

Sergeant Carroll, 24, represents a broad swath of members of the military — a largely young, healthy set of Americans from every corner of the nation — who are declining to get the shot, which for now is optional among personnel. They cite an array of political and health-related concerns.

But this reluctance among younger troops is a warning to civilian health officials about the potential hole in the broad-scale immunity that medical professionals say is needed for Americans to reclaim their collective lives.

“At the end of the day, our military is our society,” said Dr. Michael S. Weiner, the former chief medical officer for the Defense Department, who now serves in the same role for Maximus, a government contractor and technology company. “They have the same social media, the same families, the same issues that society at large has.”

Roughly one-third of troops on active duty or in the National Guard have declined to take the vaccine, military officials recently told Congress. In some places, such as Fort Bragg, N.C., the nation’s largest military installation, acceptance rates are below 50 percent.

“We thought we’d be in a better spot in terms of the opt-in rate,” said Col. Joseph Buccino, a spokesman at Fort Bragg, one of the first military sites to offer the vaccine.

While Pentagon officials say they are not collecting specific data on those who decline the vaccine, there is broad agreement that refusal rates are far higher among younger members, and enlisted personnel are more likely to say no than officers. Military spouses appear to share that hesitation: In a December poll of 674 active-duty family members conducted by Blue Star Families, a military advocacy group, 58 percent said they would not allow their children to receive the vaccine.

For many troops, the reluctance reflects the concerns of civilians who have said in various public health polls that they will not take the vaccine. Many worry the vaccines are unsafe or were developed too quickly.

Some of the concerns stem from misinformation that has run rampant on Facebook and other social media, including the false rumor that the vaccine contains a microchip devised to monitor recipients, that it will permanently disable the body’s immune system or that it is some form of government control.

In some ways, vaccines are the new masks: a preventive measure against the virus that has been politicized.

There are many service members like Sergeant Carroll, officials said, who cite the rare chance to avoid one vaccine among the many required, especially for those who deploy abroad.

Young Americans who are not in the military, and who believe they do not need to worry about becoming seriously ill from the coronavirus, are likely to embrace their own version of defiance, especially in the face of confusing and at times contradictory information about how much protection the vaccine actually offers.

Latest Updates

- Black Congress Members urge African-Americans to get vaccinated.

- Top health official in Memphis resigns after the state finds 2,400 wasted doses.

- South Carolina’s governor rolls back restrictions, but cases away from the coast remain stubbornly high.

“I don’t think anyone likes being told what to do,” Dr. Weiner said. “There is a line in the American DNA that says, ‘Just tell me what to do so I know what to push back on.’ ”

Other troops cite the anthrax vaccine, which was believed to cause adverse effects in members of the military in the late 1990s, as evidence that the military should not be on the front lines of a new vaccine.

In many cases, the reasons for refusal include all of the above.

A 24-year-old first-class air woman in Virginia said she declined the shot even though she is an emergency medical worker, as did many in her squadron. She shared her views only on the condition of anonymity because, like most enlisted members, she is not permitted to speak to the news media without official approval.

“I would prefer not to be the one testing this vaccine,” she explained in an email She also said that because vaccine access had become a campaign theme during the 2020 race for the White House, she was more skeptical, and added that some of her colleagues had told her they would rather separate from the military than take the vaccine should it become mandatory.

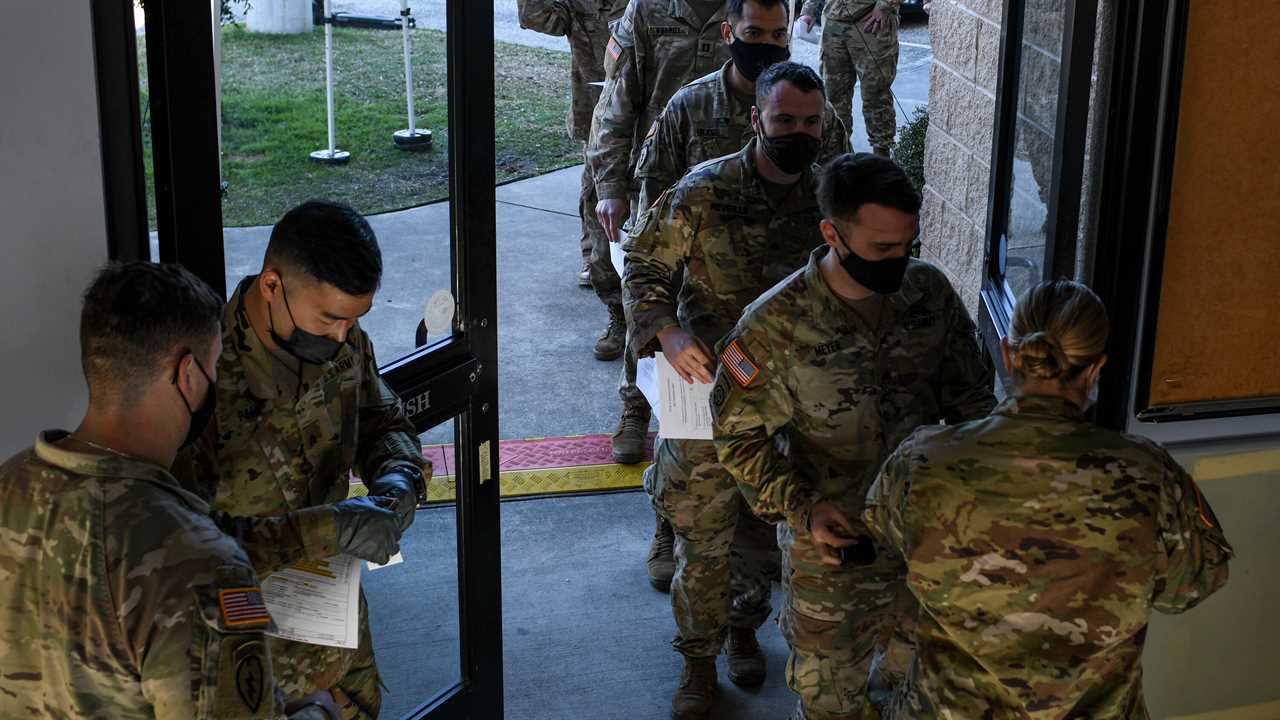

The military has been offering the vaccine to older personnel, troops on the medical front lines, immediate response and contingency forces, some contractors who fall into those groups and some dependents of active-duty troops.

Hundreds of thousands of people in those categories have received shots so far.

The vaccine, unlike many other inoculations, is not required by the military at this time because it has been approved for emergency use by the Food and Drug Administration. Once it becomes a standard, approved vaccine, the military can order troops to take the shot.

The prevalence of fear about the safety and efficacy of the vaccine has frustrated military officials.

“There is a lot of misinformation out there,” Robert G. Salesses, an acting assistant secretary of defense, told members of the Senate Armed Services Committee on Thursday. One member of the committee, Senator Gary Peters, Democrat of Michigan, suggested that the military personnel who refused vaccines “risk an entire community” where bases are.

While military leaders insist that vaccine acceptance rates will rise as safety information continues to spread, officials and advocacy groups are scrambling to improve the rates, holding information sessions with health care leaders like Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. On some bases, health care workers follow up with those who refuse the vaccine to explore their reasons.