Politics is serious business. It often feels existential. Exhausting. Infuriating. Bone-dry. Confusing.

Can it also be fun?

Eliot Nelson insists it can be. And to prove it, he’s turning politics into a game.

A video game.

For the past three years, Nelson has been working on Political Arena, which he bills as “the first truly in-depth video game about American democracy.” For those of a certain age, think SimCity meets The Oregon Trail — with a little Grand Theft Auto thrown in. Nelson wants to educate the masses about the ins and outs of how their government really works. And entertain them, too.

“Politics is gripping,” Nelson told us. “It’s one of the most popular subjects across time. The thrill of wielding power is inherently exciting.”

As one early online ad for the game puts it, “Seek fame or infamy in a fully simulated political world, complete with high stakes campaign strategizing, backroom deals, scandals, special interests, and the press. Be the politician of your dreams (or nightmares).”

From D.C. in-jokes to storyboards

Nelson spent the early part of his career as a journalist in Washington. His much-loved newsletter on Congress, HuffPost Hill, was an extension of his personality — a blend of earnest wonkery, serious legislative coverage and lots and lots of wisecracks.

“It was the one tipsheet that I would recommend to my friends who were not in politics,” said Jess McIntosh, who was a press secretary for former Senator Al Franken and is now advising the video game project. “I still miss it.”

The first iteration of the game will be released later this year. Nelson acknowledged that the post-Jan. 6 environment has cast a dark cloud. But, he added, “Politics contains multitudes, and there are moments of levity and dark humor.”

After crowdsourcing more than $100,000 in seed money on Kickstarter, he assembled a scrappy team of game designers, marketers and grizzled industry veterans. They puzzled through how the gameplay should work, poring over storyboards and seeking input from hard-core political junkies and strategy-game fans.

How the game works

The focal point of Political Arena is accruing power.

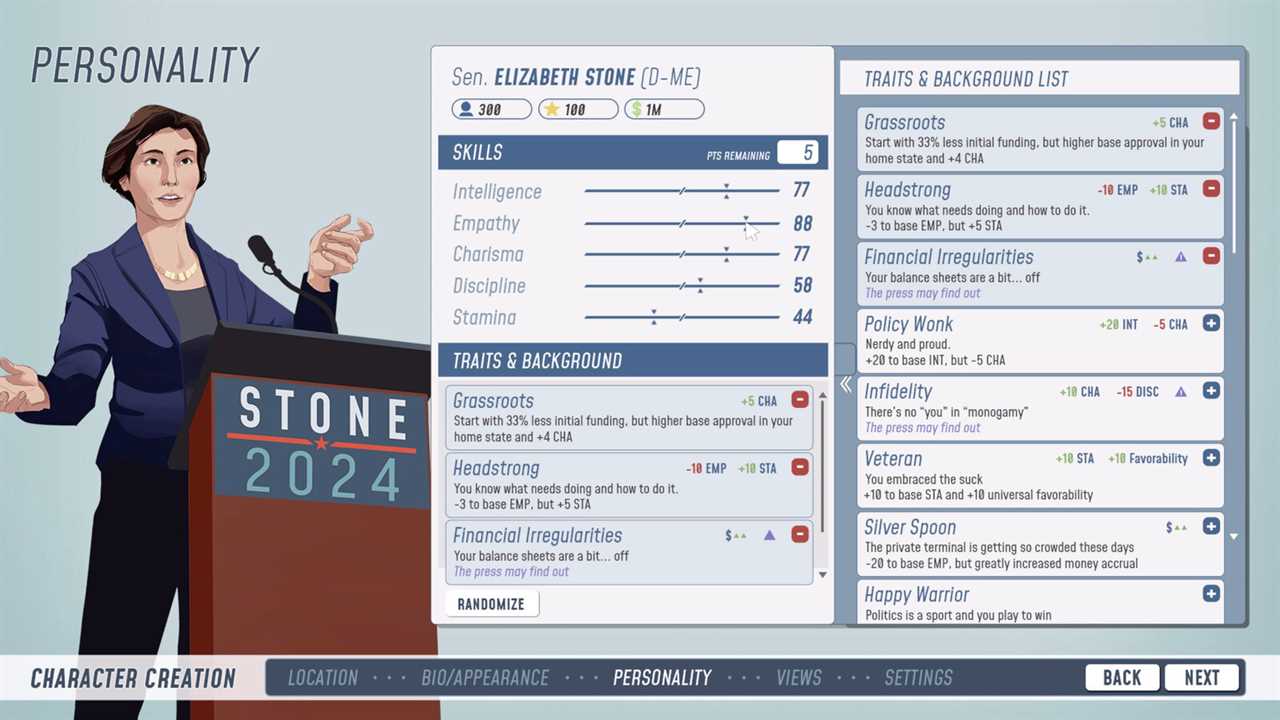

You start by creating your own politician, picking a limited number of points to spend on a few skills and character traits. Are you a media-obsessed, populist firebrand or a legislative lion? Is your goal to become president, master of the Senate or a spitball-throwing House backbencher?

To simulate the real world, the software generates politicians who hew as closely to the politics of their district or state as possible. Want to be a certain senior senator from Kentucky? Call your new avatar Mitch McConnell and have a blast.

For now, your adversary is the computer and the scenarios it throws at you. But future versions of the game might allow players to compete against one another online.

There are three kinds of currency in the game: money, fame and political capital, a kind of clout score. As in real life, the more of each you amass, the better you do. You might be asked, for instance, to handle the political fallout when your vice president tweets a racist meme or gets caught having an extramarital affair with a secretary.

“This isn’t the kind of game where you’re killing orcs with an ax,” Nelson said.

Patrick Curry, the chief executive of FarBridge, a studio based in Austin, Texas, that is helping to develop the software for Political Arena, said his team is also working on “boss battle” moments — those intense showdowns at the end of each level in a classic video game.

A boss battle might be a high-stakes news conference or a campaign debate. “And it doesn’t have to look like a PBS version of the debate, either,” Curry said.

‘How and why our politics happen’

Well before leaving HuffPost in 2018, Nelson, a lifelong gamer, had been noodling over how a video game might be able to reach an entirely different audience.

“It’s like trying to understand football without ever watching a game of football,” Nelson said. He added, alluding to Oregon Trail: “People are more fluent in what you need in your wagon and how much buffalo meat you should carry than they are about how bills are passed.”

McIntosh, the former press secretary for Franken and a political consultant, said that games can teach Americans how their democracy works by creating a degree of intimacy that journalism can’t quite match.

“It’s weird that you can role-play just about any experience in life, including going to the grocery store in another country, but you can’t play a political campaign,” she said. “It just feels like understanding how and why our politics happen is more important than ever.”

There have been past attempts to make video games about politics. But either the technology wasn’t advanced enough to make them appeal to a large audience, or the focus was too much on education and not enough on fun.

The closest thing to a commercial forebear to Political Arena might be President Elect, a primitive simulation game that debuted in 1981 and went through several iterations before fading from memory in the late 1980s.

When we last spoke with Nelson, he was working out kinks in Political Arena’s legislative voting system, to allow for what he called “Joe Manchin-style, last-minute negotiations” on the floor of the Senate.

He was trying to figure out how to simulate the adrenaline rush of watching a big vote like the one to authorize the Affordable Care Act in 2010. And he was hashing out the complexities of how best to enable players to strike the unseemly sorts of bargains that happen in the real-world Congress all the time.

“A game that doesn’t include the good and bad would be making matters worse,” he said. “Politics is compelling in part because of the warts.”

What to read

The congressional committee investigating the Jan. 6 riot at the Capitol has subpoenaed Peter Navarro, a former White House adviser to Donald Trump, Luke Broadwater reports.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi endorsed a proposed ban on lawmakers trading stocks, amid a bipartisan push led by vulnerable House members, Jonathan Weisman reports.

The director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Dr. Rochelle Walensky, said the agency was working on new health guidance as Democratic governors begin lifting pandemic-related restrictions, but cautioned against moving too quickly, Sheryl Gay Stolberg reports.

postcard FROM WYOMING

Two tales of one phone call

By Reid J. Epstein

CHEYENNE, Wyo. — To pro-Trump Republicans in Wyoming, Representative Liz Cheney has been out of sight on the campaign trail, but not out of mind.

She hasn’t appeared at a state Republican Party function in more than two years and hasn’t been to an in-person event for any of the party’s 23 county chapters since 2020. Her opposition to Trump has forced her into a kind of exile from Wyoming’s Republican Party apparatus.

And her former political ally, who’s now running against her after winning Trump’s endorsement?

Well, they don’t talk much.

The last time Cheney spoke to her Republican primary opponent, Harriet Hageman, was in a phone call a few weeks after the 2020 election. In separate interviews, each shared her side of that conversation.

Cheney had just publicly urged Trump to concede he had lost, a statement that proved highly unpopular with Wyoming Republicans. She was calling around to gauge the political blowback in her home state.

When she called Hageman — the two had been close enough politically that Hageman introduced Cheney at the state party convention in 2016 — Cheney said she expected her to agree on the legitimacy of President Biden’s victory.

“She is somebody who has been committed to the rule of law,” Cheney explained. “She’s an attorney.”

But the conversation did not go well. Hageman recalled telling Cheney of Trump’s objections to the election results in Georgia, Pennsylvania and other battleground states.

“I just said, ‘I think that there were some legitimate questions and we have every right to ask them,’” Hageman said. “This is America. We get to ask questions.”

Cheney recalled informing Hageman that it was unconstitutional to object to other states’ electoral votes. And she said that she warned of setting a precedent that would allow Democrats in Congress to decide the legality of Wyoming’s electoral votes.

“I was surprised that she seemed not to be exactly where I was on the issue,” Cheney said. “I thought she would have been.”

Hageman said Cheney ended the call with a scold — telling Hageman that it was time for Mr. Trump and his allies to accept the results of the election, given his myriad legal defeats.

“I said, ‘We have the right to look into that,’” Hageman said. “And she just flat told me, ‘You’re wrong.’ And I have not spoken to her since.’”