WASHINGTON — Congressional Democrats, searching for any way forward on legislation to protect voting rights, find themselves softening their once-firm opposition to a form of restriction on the franchise that they had long warned would be Exhibit A for voter suppression: voter identification laws.

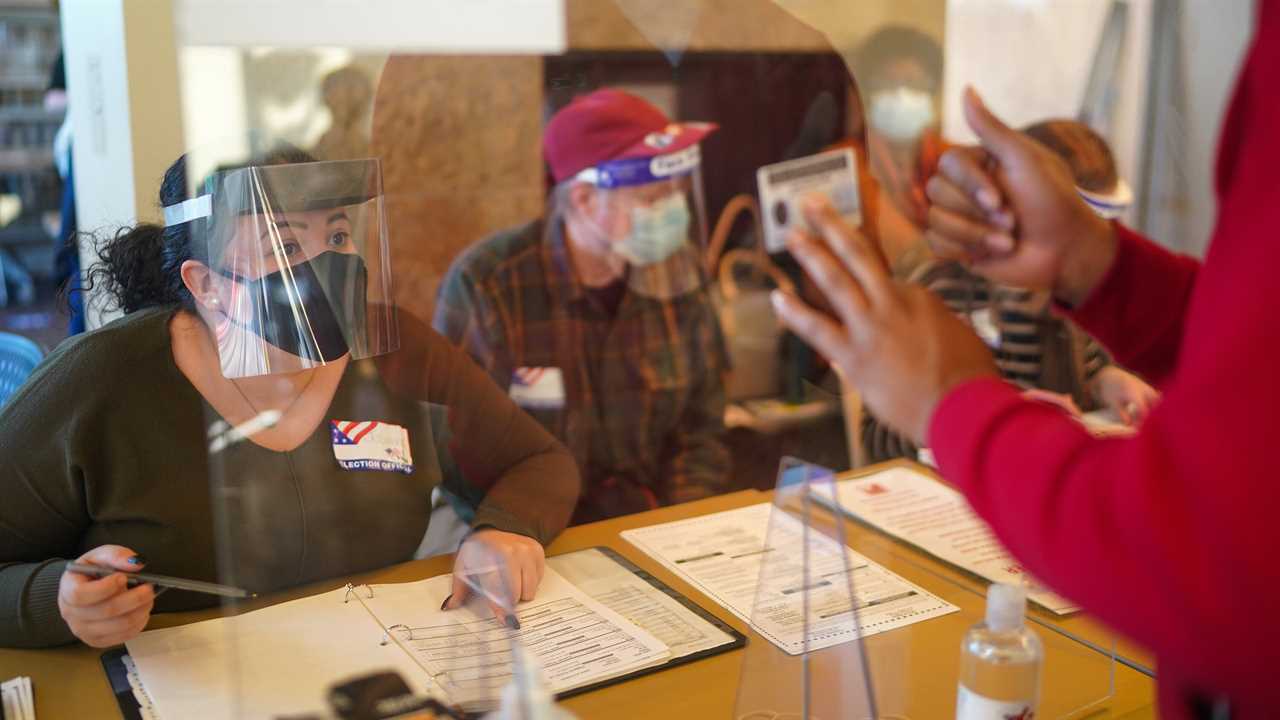

Any path to passing the far-reaching Democratic elections legislation that Republicans blocked with a filibuster on Tuesday will almost certainly have to include a compromise on the bill’s near-blanket ban on state laws that require voters to present photo identification before they can cast a ballot. As such laws were first cropping up decades ago, Democrats fought them tooth and nail, insisting that they would be an impossible barrier to scale for the nation’s most vulnerable voters, especially older people and people of color.

But in recent years, as the concept of voter identification has become broadly popular, the idea that voters bring some form of ID to the polls has been accepted by Democrats ranging from Senator Joe Manchin III of West Virginia on the center-right to Stacey Abrams of Georgia, a hero of the left.

“As I have always said, a person should have to confirm that they are who they are in order to vote,” Senator Raphael Warnock, a Democrat from Georgia and a key ally of Ms. Abrams, said in an interview. “What I get concerned about is when you say gun licenses are OK, when a student ID is not. Then I think any reasonable person has to ask, ‘Well, what’s that game?’”

And compared with newer state laws that restrict early voting and mail-in voting, limit ballot drop boxes and allow partisan elected officials to take on a greater role overseeing elections, voter identification suddenly seems like an expendable bargaining chip for some Democrats.

“I have been fighting voter ID since 1990 when I was in the State Legislature,” said Representative Gwen Moore, a Black Democrat from Wisconsin, where Republicans adopted an ID law a decade ago that Democrats said would devastate universal access to the ballot box. “I don’t know that it’s less important, but given the gravity of all the other things that they want to do, like shutting down polling sites, in the hierarchy of needs, I really believe we give them their old No. 1 thing.” Then, she said, Democrats need to demand that other impediments to the ballot box be struck down.

While the idea of voter identification requirements remains popular in national polling, the implementation of such laws throughout history has at times been discriminatory and even weaponized to target and suppress votes in certain communities. Numerous federal court rulings in the past decade alone have struck down voter ID laws in Georgia, Texas and North Carolina as discriminatory.

In recent years, voter ID laws have been adopted in varying degrees of strictness from Washington State to Florida, with the strictest measures enacted in the Southeast and Wisconsin. Republican-led legislatures are now pushing ahead with new bills to toughen identification rules for absentee and mail-in ballots.

And this year, at least 101 bills with restrictive voter ID provisions have been introduced in 35 states, according to data from the Voting Rights Lab, a liberal-leaning voting rights group. Georgia, Florida, Montana, Iowa, Wyoming and Arkansas have already passed new voter identification laws.

In the fight over the far-reaching Democratic legislation known as the For the People Act, Republicans seized on shifts in national attitudes toward basic requirements for identification to declare the entire measure unpopular in large part because of its voter ID provision. Democrats, plotting a second act for the bill, are looking to neutralize that argument.

“We are looking for a middle ground,” said Senator Amy Klobuchar, Democrat of Minnesota and the chairwoman of the Senate Rules Committee, which is responsible for finding a way forward after a motion just to take up the broader bill failed on a 50-to-50 vote on Tuesday, 10 votes short of the number needed to break a filibuster.

The For the People Act would set minimum standards for early and mail-in voting, roll back voting restrictions that Republican state legislatures have enacted in the wake of G.O.P. losses in 2020, extend taxpayer financing to congressional campaigns, end gerrymandering of House districts, and apply new standards of ethics to the president and vice president.

While Democrats say the measure represents nothing short of salvation for American democracy, Republicans have called it a breathtaking effort to grab control of election administration from the states. Even as the federal bill is bottled up, Republicans in state legislatures have pushed nearly 400 new bills and laws that would usher in a host of new voting restrictions, with at least 24 of those bills already signed into law.

To counter the claims of overreach, Mr. Manchin produced a compromise that would jettison the public financing of elections — denounced by Republicans as “welfare for politicians” — and revise the voter identification provisions in the bill.

Under Mr. Manchin’s version, states would be allowed to require photo identification, but they would have to define ID broadly — to include student IDs, hunting licenses, conceal-carry gun permits, and any form of government paper that includes the voter’s name, like a utility bill.

If voters cannot provide such ID, they could cast a provisional ballot, subject to signature verification against their voter registration card. Even if the signature cannot be verified, the voter would be given 10 days to return to a voting administrator with a valid ID.

Some Black lawmakers — whom Democratic leaders have looked to for advice on the voting bill — have examined the Manchin proposal and have generally blessed it. Representative Joe Neguse, Democrat of Colorado, said Wednesday that coming to a compromise on individual provisions like the voter ID section was important, but that ultimately, none of it would pass without changes to the Senate’s legislative filibuster.

“For me, the larger debate that is probably more critical is reforming the filibuster,” he said.

Senator Angus King, an independent from Maine, said Wednesday that the next step would be nailing down a compromise that Mr. Manchin will accept, then looking for Republican support. Ms. Klobuchar promised to take her committee on the road next week, when the Senate begins a two-week recess, to try to add political pressure.

And many voting rights and civil rights groups, which have been stalwart supporters of the bill in its entirety, are signaling flexibility on voter ID, reiterating their previous support for such measures within the right confines.

“Basic voter ID has been a part of voting since the beginning, and both Democrats and Republicans agree that people should provide proof of who they are before casting ballots,” Ms. Abrams, the former Democratic candidate for governor in Georgia, wrote in her book “Our Time Is Now” last year. “What is changed in recent years is the type of identification required and the difficulty or expense of securing the necessary documents.” She made similar comments last week on CNN.