GUANTÁNAMO BAY, Cuba — Seven senior U.S. military officers who sentenced a terrorist to 26 years in prison last week after hearing graphic descriptions of his torture by the C.I.A. wrote a letter calling his treatment “a stain on the moral fiber of America.”

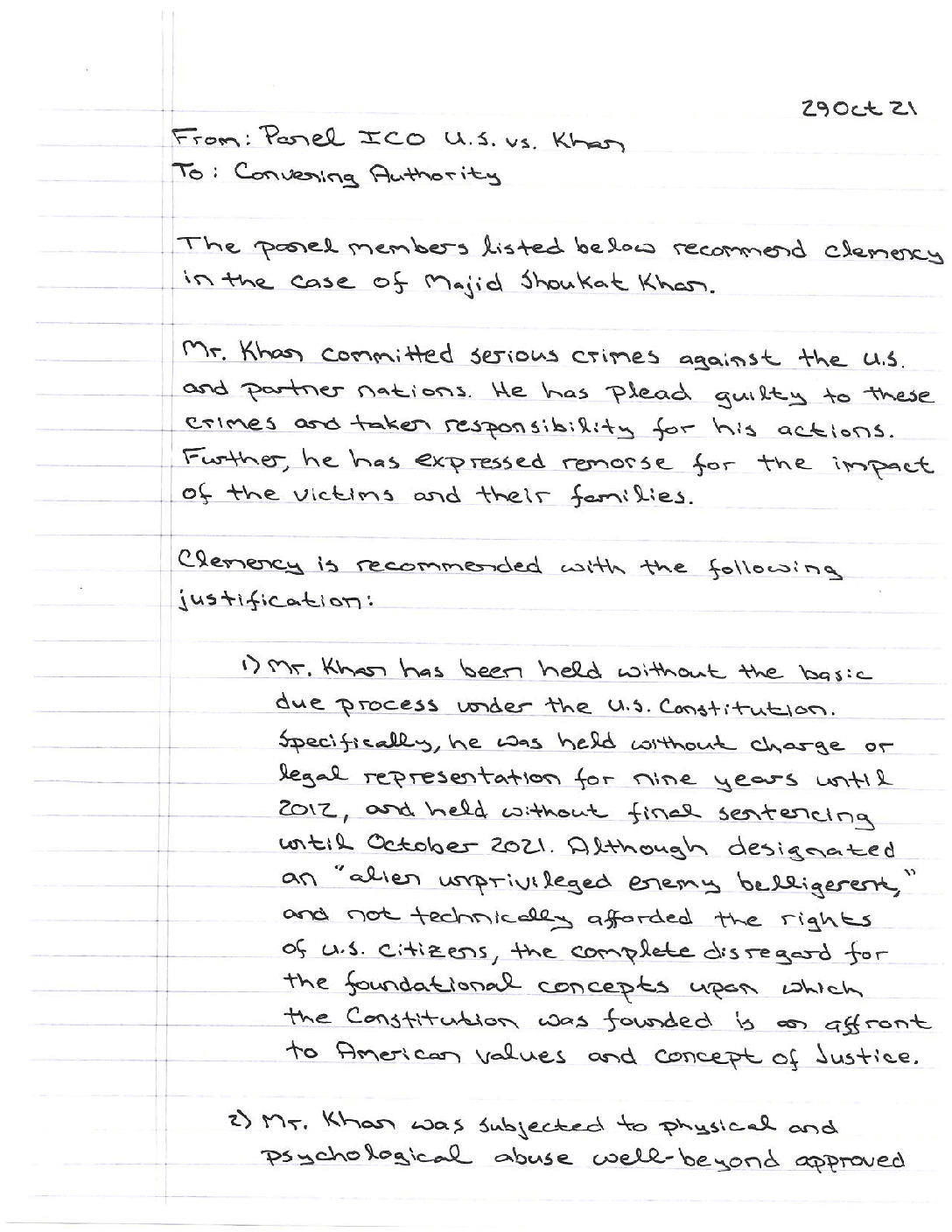

The rebuke of the U.S. government’s treatment of Majid Khan, a suburban Baltimore high school graduate turned Qaeda courier, was contained in a two-page handwritten letter urging the senior Pentagon official overseeing the war court to grant clemency. It was signed by seven of the eight members of the sentencing jury — six Army and Navy officers and a Marine, using their juror numbers.

The panel of active-duty officers was brought to Guantánamo Bay last week to hear evidence and decide a sentence of 25 to 40 years. Deliberations began after Mr. Khan spent two hours describing in grisly detail the violence that C.I.A. agents and operatives inflicted on him in dungeonlike conditions in prisons in Pakistan, Afghanistan and a third country, including sexual abuse and mind-numbing isolation, often in the dark while he was nude and shackled.

“Mr. Khan was subjected to physical and psychological abuse well beyond approved enhanced interrogation techniques, instead being closer to torture performed by the most abusive regimes in modern history,” according to the letter, which was obtained by The New York Times.

The panel also responded to Mr. Khan’s claim that after his capture in Pakistan in March 2003, he told interrogators everything, but “the more I cooperated, the more I was tortured,” and so he subsequently made up lies to try to mollify his captors.

“This abuse was of no practical value in terms of intelligence, or any other tangible benefit to U.S. interests,” the letter said. “Instead, it is a stain on the moral fiber of America; the treatment of Mr. Khan in the hands of U.S. personnel should be a source of shame for the U.S. government.”

In his testimony on Thursday night, Mr. Khan became the first former prisoner of the C.I.A.’s so-called black sites to publicly describe in detail the violence and cruelty that U.S. agents used to extract information and to discipline suspected terrorists in the clandestine overseas prison program that was set up after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. In doing so, Mr. Khan also provided a preview of the kind of information that might emerge in the death penalty trial of the five men accused of plotting the Sept. 11 attacks, a process that has been bogged down in pretrial hearings for nearly a decade partly because of secrecy surrounding their torture by the C.I.A.

The agency declined to comment on the substance of Mr. Khan’s descriptions of the black sites, which prosecutors did not seek to rebut. It said only that its detention and interrogation program, which ran the black sites, ended in 2009.

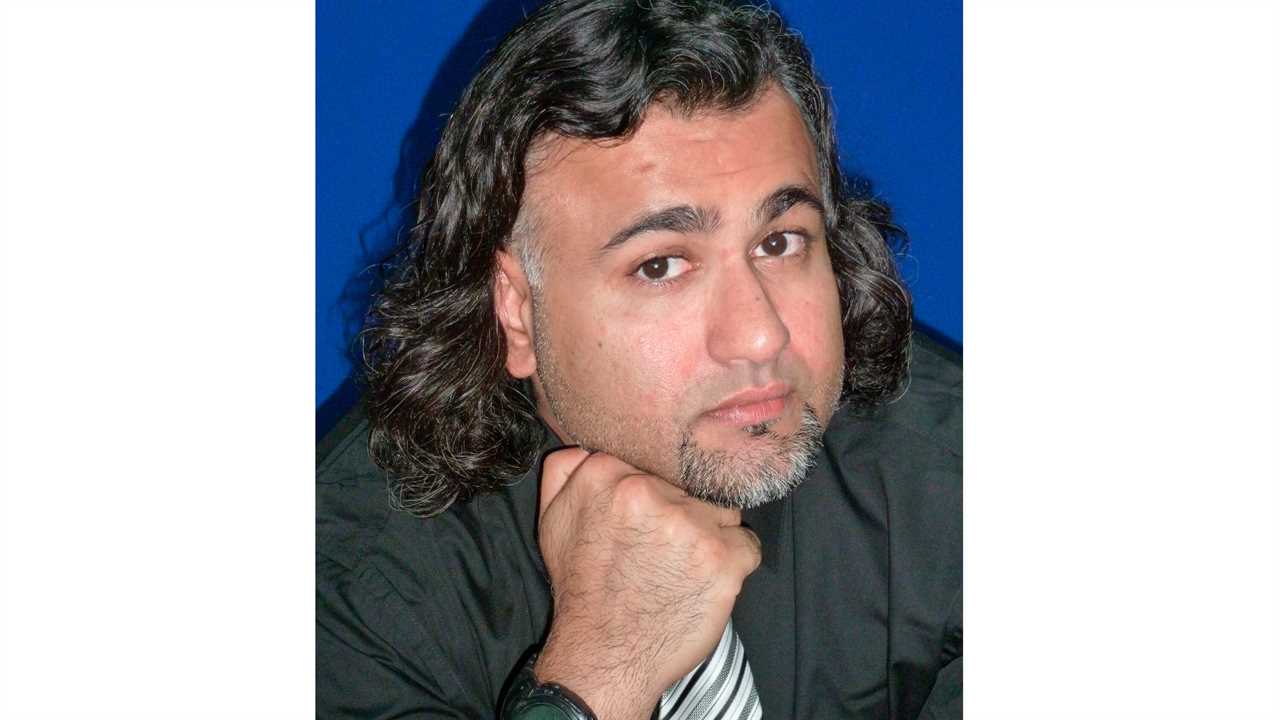

Mr. Khan, 41, was held without access to either the International Red Cross, the authority entrusted under the Geneva Conventions to visit war prisoners, or to a lawyer until after he was transferred to Guantánamo Bay in September 2006. He pleaded guilty in February 2012 to terrorism crimes, including delivering $50,000 from Al Qaeda to an allied extremist group in Southeast Asia, Jemaah Islamiyah, that was used to fund a deadly bombing of a Marriott hotel in Jakarta, Indonesia, five months after his capture. Eleven people were killed, and dozens more were injured.

The clock on his prison sentence began ticking with his guilty plea in 2012, meaning the panel’s 26-year sentence would end in 2038.

But Mr. Khan, who has cooperated with the U.S. government, helping federal and military prosecutors build cases, has a deal that was kept secret from the jury that could end his sentence in February or in 2025 at the latest.

The letter also condemned the legal framework that held Mr. Khan without charge for nine years and denied him access to a lawyer for the first four and half as “complete disregard for the foundational concepts upon which the Constitution was founded” and “an affront to American values and concept of justice.”

The Handwritten Document

This letter was drafted in the deliberation room recommending clemency for Majid Khan. Seven members of Mr. Khan’s eight-officer jury signed it, using their panel numbers. The jury was drawn from a pool of 20 active-duty officers who were brought to Guantánamo Bay on Oct. 27.

Read Document 2 pagesIan C. Moss, a former Marine who is a civilian lawyer on Mr. Khan’s defense team, called the letter “an extraordinary rebuke.”

“Part of what makes the clemency letter so powerful is that, given the jury members’ seniority, it stands to reason that their military careers have been impacted in direct and likely personal ways by the past two decades of war,” he said.

At no point did the jurors suggest that any of Mr. Khan’s treatment was illegal. Their letter noted that Mr. Khan, who never attained U.S. citizenship, was held as an “alien unprivileged enemy belligerent,” a status that made him eligible for trial by military commission and “not technically afforded the rights of U.S. citizens.”

But, the officers noted, Mr. Khan pleaded guilty, owned his actions and “expressed remorse for the impact of the victims and their families. Clemency is recommended.”

The jury foreman, a Navy captain, said in court that he took up a request by Mr. Khan’s military defense lawyer, Maj. Michael J. Lyness of the Army, to consider drafting a letter recommending clemency. It was addressed to the convening authority of military commissions, the senior Pentagon official overseeing the war court, a role that is currently held by Col. Jeffrey D. Wood of the Arkansas National Guard.

Unknown to the jurors, Colonel Wood had reached an agreement with Mr. Khan to evaluate his cooperation with the government and reduce his sentence. In exchange, Mr. Khan and his legal team agreed to drop their effort to call witnesses to testify about his torture, much of it most likely classified, as long as he could tell his story to the jury.

The jurors were also sympathetic to Mr. Khan’s account of being drawn to radical Islam in 2001 at age 21, after the death of his mother, and being recruited to Al Qaeda after the Sept. 11 attacks. “A vulnerable target for extremist recruiting, he fell to influences furthering Islamic radical philosophies, just as many others have in recent years,” the letter said. “Now at the age of 41 with a daughter he has never seen, he is remorseful and not a threat for future extremism.”

The panel was provided with nine letters of support for Mr. Khan from family members, including his father and several siblings — American citizens who live in the United States — as well as his wife, Rabia, and daughter, Manaal, who were born in Pakistan and live there.

Although rarely done, a military defense lawyer can ask a panel for letters endorsing mercy, such as a reduction of a sentence, for a service member who is convicted at a court-martial. But this was the first time the request was made of a sentencing jury at Guantánamo, where accused terrorists are being tried by military commission.