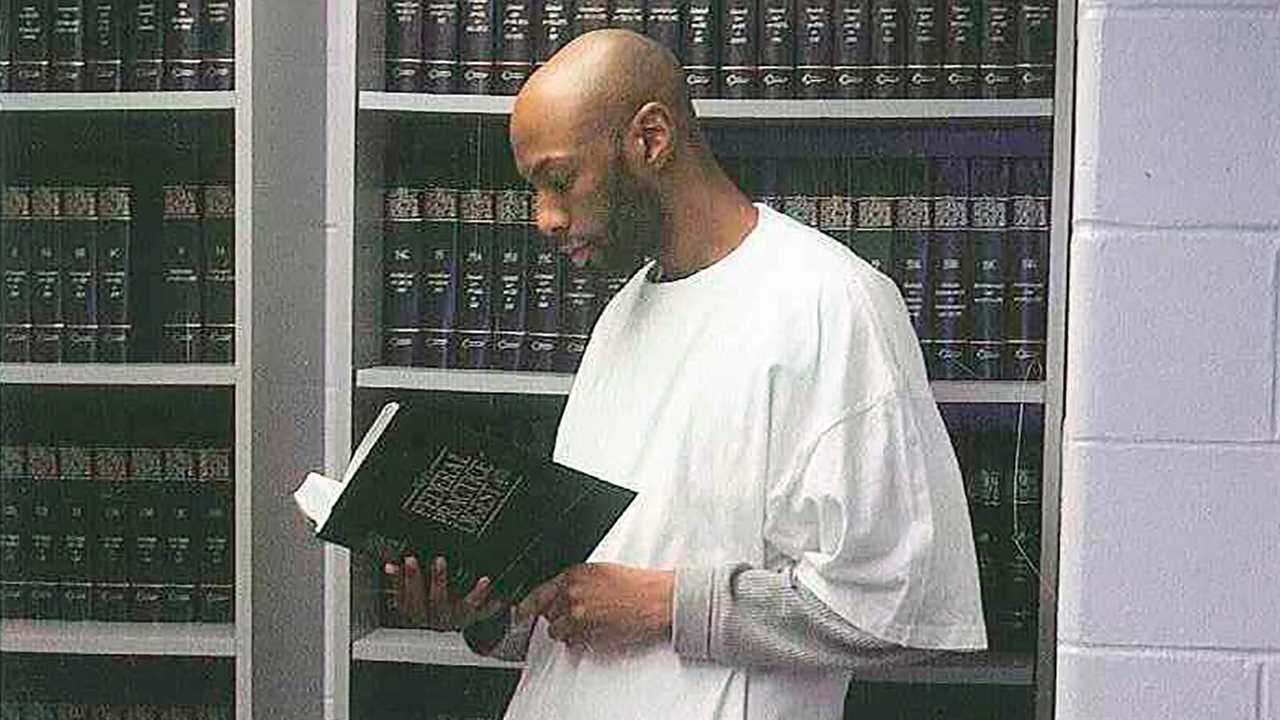

WASHINGTON — The Trump administration executed Dustin J. Higgs early Saturday for his part in a triple murder in 1996, marking the 13th and final scheduled federal execution under President Trump.

Aided by a conservative majority on the Supreme Court, Mr. Trump revived federal capital punishment in July after a 17-year hiatus, a stark contrast with the waning public support during that period for the death penalty.

Mr. Higgs could be the last person put to death by the federal government for some time. President-elect Joseph R. Biden Jr., who will be inaugurated on Wednesday, has said he is opposed to the death penalty and has pledged that he would work to pass legislation ending capital punishment at the federal level.

In 2019, the attorney general at the time, William P. Barr, announced the Trump administration’s intention to resume executions of federal death row inmates using the lethal injection of a single drug, pentobarbital. Legal challenges briefly blocked those efforts.

In June, the Supreme Court cleared the way for the government to proceed, and the administration moved quickly to execute more than a dozen prisoners, sometimes scheduling two, three or even four at a time. Twice, the government carried out three executions in less than a week.

Mr. Higgs was pronounced dead at 1:23 a.m. at the federal correctional complex in Terre Haute, Ind., in accordance with the nine capital sentences recommended by a federal jury, according to the Bureau of Prisons.

On Friday night, the Supreme Court voted 6 to 3 to clear the way for Mr. Higgs’s execution to proceed, with members of the more liberal wing dissenting. In a scathing written dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor accused the court of repeatedly sidestepping “its usual deliberative processes, often at the government’s request,” allowing the Trump administration to proceed “with an unprecedented, breakneck timetable of executions.”

“This is not justice,” she wrote. “After waiting almost two decades to resume federal executions, the government should have proceeded with some measure of restraint to ensure it did so lawfully. When it did not, this court should have. It has not.”

The Justice Department also finalized a rule last year that would allow the government to use new methods of execution, including death by electrocution or firing squad.

Mr. Higgs’s execution was the third in four days, after the administration executed Lisa M. Montgomery, the only woman on federal death row, on Wednesday and Corey Johnson on Thursday.

Mr. Higgs’s case stemmed from an evening in 1996, when he and two other men drove from Mr. Higgs’s apartment in Laurel, Md., to Washington, the Justice Department said. They picked up three women — Tamika Black, Mishann Chinn and Tanji Jackson — and, after stopping at a liquor store, then returned to Mr. Higgs’s apartment to drink alcohol and listen to music. Early the next day, Mr. Higgs and Ms. Jackson began to argue, prompting Ms. Jackson to grab a knife. One of the men, Willis M. Haynes, broke up the fight.

Still angered, Ms. Jackson left the apartment with the other women, making a threat as she exited, and appeared to take note of Mr. Higgs’s license plate, according to a court filing from the Justice Department. Mr. Higgs grabbed a firearm from a drawer, and the three men met up with the women outside. The women got in the men’s car, apparently promised that they would be driven home, but instead, Mr. Higgs drove to a secluded area in the Patuxent Research Refuge, which is federal property.

Mr. Higgs’s defense team disputes what happened next. The Justice Department said Mr. Higgs ordered the women out of the vehicle, gave the gun to Mr. Haynes, and instructed him to kill them. Mr. Haynes then fatally shot each of the women. Mr. Higgs’s lawyers argued that the evidence supporting the theory that Mr. Higgs ordered the killings was dubious.

Latest Updates

- The pandemic slowed global migration sharply in 2020.

- A leading public health organization takes stock of U.S. testing strategy.

- Britain will require travelers from abroad to show a negative test, then quarantine.

“I’d like to say I am an innocent man,” Mr. Higgs said, before the lethal injection began, according to a report from a journalist in attendance. “I did not order the murders.”

Victor Gloria, the third man, agreed to cooperate with the government’s murder case after he was arrested in 1998 on federal drug charges. He pleaded guilty to being an accessory after the fact to the murders and received 84 months in prison with three years’ supervised release.

Mr. Haynes, whose jury failed to reach a unanimous verdict on the death penalty, received life in prison without the possibility of release.

But Mr. Higgs was sentenced to death, a punishment that his lawyers argued was “arbitrary and inequitable” compared with that of the man who shot the gun. His defense team pointed to a declaration that Mr. Haynes signed years after the crime in which he claimed that Mr. Higgs did not threaten him nor make him do anything. Mr. Haynes claimed he shot the girls because he feared for Mr. Higgs’s life.

In a statement provided by the Bureau of Prisons, the sister of Ms. Jackson, one of Mr. Higgs’s victims, said that the news of Mr. Higgs’s execution date brought “mixed emotions.” His family is now going through the same pain hers experienced, she added.

“On one hand, I felt we were finally going to get justice, but on the other, I felt sad for your family,” she said. “When the day is over, your death will not bring my sister and the other victims back. This is not closure, this is the consequence of your actions.”

Mr. Trump was not receptive to pleas for leniency for Mr. Higgs or for any of the 12 inmates who were executed before him. The Supreme Court — which now has three Trump appointees, solidifying its conservative majority — also denied his requests for reprieve. Shortly before Mr. Higgs’s execution, the justices had vacated a stay from the Fourth Circuit that temporarily blocked the government.

Each of the court’s more liberal justices indicated that they disagreed. Justice Stephen G. Breyer listed questions that the recent federal death penalty cases have raised, among them, “To what extent does the government’s use of pentobarbital for executions risk extreme pain and needless suffering?” and, “Has an inmate demonstrated a sufficient likelihood that she is mentally incompetent — to the point where she will not understand the fact, meaning, or significance of her execution?”

“None of these legal questions is frivolous,” he wrote. “What are courts to do when faced with legal questions of this kind? Are they simply to ignore them? Or are they, as in this case, to ‘hurry up, hurry up’? That is no solution.”

But the longer the delay, he argued, the weaker the “basic penological justifications” and the greater the psychological suffering for the prisoner. As he has done before, Justice Breyer called into question the constitutionality of the death penalty itself.

In her own dissent, Justice Sotomayor argued that, over the course of the execution spree, the court has consistently rejected the prisoners’ “credible claims for relief,” intervened to lift stays put in place by lower courts and made weighty decisions in just a few short days or even hours. Very few of these decisions, she noted, offered any public explanation for the court’s rationale.

Both Mr. Higgs and Mr. Johnson tested positive for the coronavirus last month, amid an outbreak on federal death row. This week, a federal judge in Washington briefly suspended their executions until March, citing the risk of the prisoners suffering “a sensation of drowning akin to waterboarding” with the government’s lethal injection protocol while still recovering from Covid-19. But a split panel of judges on the District of Columbia Circuit overturned that order, clearing a remaining barrier for the executions to proceed.

Judge Gregory G. Katsas of the Appeals Court, joined by another judge on the panel, cited Supreme Court precedent that states that the Eighth Amendment “‘does not guarantee a prisoner a painless death — something that, of course, isn’t guaranteed to many people.’”

Among the efforts to halt the executions, lawyers for two other men at the federal prison complex in Terre Haute sued the government on the grounds that the executions risked exposing them to the coronavirus.

In a class-action case, the inmates, neither of whom is on death row, argued that the large number of people drawn to the complex for each execution exacerbated the threat of Covid-19. Citing evidence that one or some involved in recent executions had not worn masks, the lawyers claimed that the federal government had failed to comply with a judge’s order that mandated certain measures to reduce the threat of the coronavirus.

A Bureau of Prisons official contended in a court filing that two individuals involved in the executions who had removed their masks did so only briefly so that they could clearly communicate. A federal judge in Indiana declined to issue a stay.

In a statement, Mr. Higgs’s lawyer Shawn Nolan continued to maintain that his client “never killed anyone” and that he contracted the coronavirus as a result of the “superspreader executions.” Mr. Nolan also noted that the execution of his client — a Black man — was carried out around Martin Luther King’s Birthday.

“There was no reason to kill him, particularly during the pandemic and when he, himself, was sick,” Mr. Nolan said. “Shame on all of those involved and all of those who have looked the other way.”