John Eastman’s path from little-known academic to one of the most influential voices in Donald J. Trump’s ear in the final days of his presidency began in mid-2019 on Mr. Trump’s favorite platform: television.

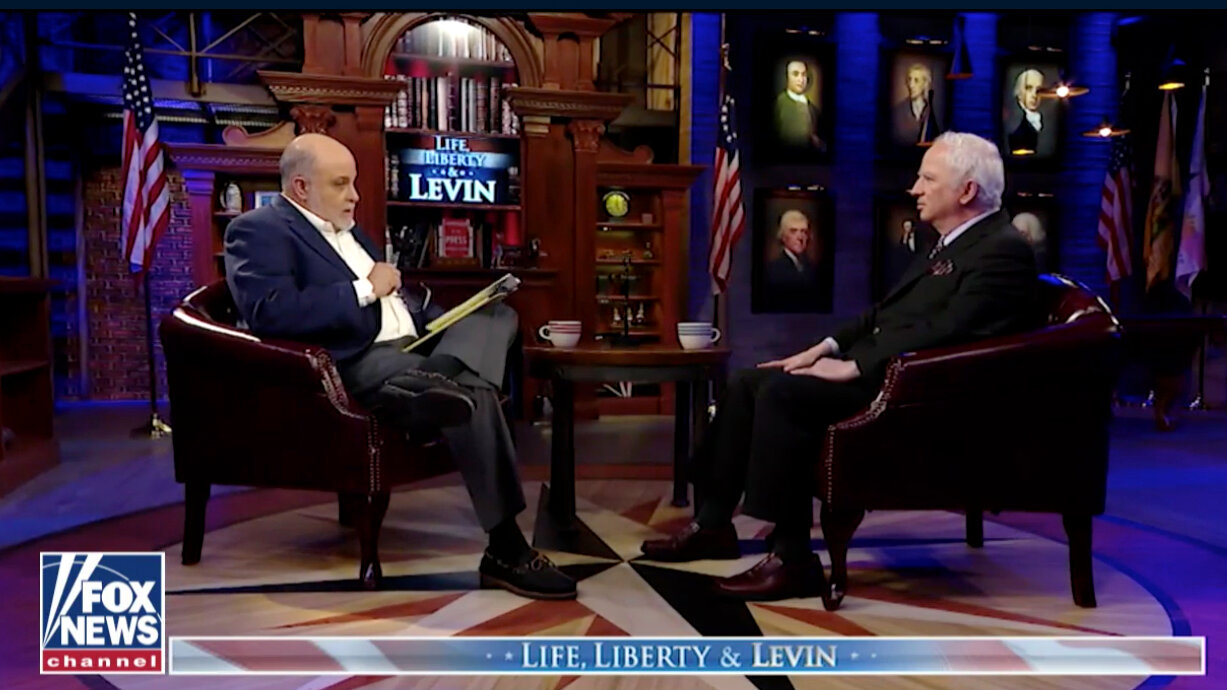

Mr. Trump, who had never met Mr. Eastman, saw him on the Fox News talk show of the far-right commentator Mark Levin railing against the Russia investigation. Within two months, Mr. Eastman was sitting in the Oval Office for an hourlong meeting.

Soon, Mr. Eastman was meeting face to face at Mr. Trump’s urging with the attorney general, William P. Barr, and telling him how Mr. Trump could unilaterally impose limits on birthright citizenship.

Then, after the November election, Mr. Eastman wrote the memo for which he is now best known, laying out steps that Vice President Mike Pence could take to keep Mr. Trump in power — measures Democrats and anti-Trump Republicans have likened to a blueprint for a coup.

Mr. Eastman’s memo is among the most alarming of the continuing revelations about the last stages of Mr. Trump’s time in the White House, when he was prompting the Justice Department to find ways to reverse his loss in the election and his top general was worried about the nuclear chain of command.

Mr. Eastman’s rise within Mr. Trump’s inner circle in the chaotic final weeks of his administration also underscores the degree to which Mr. Trump not only relied on, but encouraged, a crew of players from the fringes of politics. They became key participants in his efforts to remain in power as many of his longtime aides and lawyers refused to help him.

John R. Bolton, Mr. Trump’s former national security adviser, said in an interview that it was troubling that at such a critical juncture, Mr. Trump had pushed aside the Justice Department and White House counsel.

Instead, he said, Mr. Trump was listening to an outsider “without the institutional learning that has gone on for a couple of hundred years that undergirds the advice that is normally given to presidents that keep them in sane channels.”

Mr. Eastman’s appeal to Mr. Trump, fleshed out in interviews with Mr. Eastman and others who dealt with him during this period, rested in large part on his expansive views of presidential power — and his willingness to tell Mr. Trump what he wanted to hear.

When it came to immigration policy, a favorite topic of both men, Mr. Eastman argued that Mr. Trump could use his executive authority to impose limits on birthright citizenship — the foundational concept that anyone born in the United States is automatically a citizen — by saying it should not be applied to people born in the United States to noncitizens.

But Mr. Barr, who was increasingly finding himself having to fend off the advice of outside lawyers, television commentators and Mar-a-Lago hangers-on, dismissed the idea, saying Mr. Eastman’s argument was a stretch and ultimately impractical.

Mr. Eastman admitted Mr. Barr was right.

“Well, tell that to the president,” Mr. Barr told him.

Still, by early January 2021, amid his wide-ranging effort to overturn the election results, Mr. Trump had become so enamored of Mr. Eastman’s advice that the two teamed up in an Oval Office meeting to pressure Mr. Pence to intervene to help Mr. Trump remain in power by delaying the Jan. 6 certification of Joseph R. Biden Jr.’s victory.

In a two-page memo written by Mr. Eastman that had been circulated to the White House in the days before the certification — revealed in the new book “Peril” by the Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Robert Costa — Mr. Eastman said that Mr. Pence as vice-president was “the ultimate arbiter” of the election, essentially saying he had the power to determine who won, and that “we should take all of our actions with that in mind.”

As Mr. Trump hints at another run in 2024, Mr. Eastman remains a bridge between the former president and the continuing efforts by some of his supporters to promote specious allegations of widespread election fraud in 2020 and to undercut faith in the electoral system.

In a series of interviews, Mr. Eastman said he was continuing to investigate reports of election fraud and was writing a book on the subject. He also said he would still like to represent Mr. Trump, who faces a range of legal battles.

He declined to say whether he had advised any state legislatures — which have become hubs for Republican efforts to push claims of election fraud — on voting issues. And he insisted that his two-page memo, which he said he hastily wrote while on Christmas vacation with his family in Texas, had been taken out of context, but defended his view that Mr. Pence could have done far more to help Mr. Trump.

“I won’t be cowed by public opposition to it,” Mr. Eastman said.

He added: “There are lots of allegations out there that didn’t get their day in court and lots of people that believe them and wish they got their day in court. and I am working very diligently with several teams — statistical teams, election specialists teams, all sorts of teams — to try and identify the various claims and determine whether they have merit or there is reasonable explanation for them.”

Like many of the lawyers who worked in Mr. Trump’s administration, Mr. Eastman had strong conservative legal credentials, initially giving him a patina of respect in Mr. Trump’s inner circle.

Mr. Eastman attended law school at the University of Chicago and clerked for both Justice Clarence Thomas of the Supreme Court and Judge J. Michael Luttig, a former federal appeals court judge who President George W. Bush considered for the Supreme Court. He is a member of the conservative Federalist Society and a former dean of the law school at Chapman University in Orange County, Calif. For two decades, he ran his own small law firm that focused on representing conservatives on issues like free speech, religious liberty, abortion and immigration.

After Election Day, Mr. Eastman served as a behind-the-scenes legal quarterback of sorts for Mr. Trump, alarming some of Mr. Trump’s aides, who feared he had found someone to enable his worst instincts at one of the most dangerous moments of his presidency. And it surprised many of Mr. Eastman’s longtime friends and others, who questioned whether his access to power had skewed his vision of reality.

“You’re always at risk when every fail-safe mechanism breaks down,” Mr. Bolton said.

Mr. Eastman’s role in Mr. Trump’s efforts to remain in power began the weekend after the election in Philadelphia, where Mr. Eastman had traveled for an academic conference. At a nearby hotel, Mr. Trump’s closest aides, including Corey Lewandowski, were putting together a legal brief to challenge the results in Pennsylvania.

Mr. Eastman had put himself on the radar of Mr. Trump’s political aides during the election when Jenna Ellis, a legal adviser to Mr. Trump’s campaign, had shared on Twitter an article Mr. Eastman had written. The article, in an echo of racist questions stoked by Mr. Trump about where President Barack Obama had been born, questioned whether Kamala Harris, Mr. Biden’s running mate, could legally become president because her parents had not been born in the United States.

Now, confronting election results that showed Mr. Trump lost, one of Mr. Trump’s aides reached out to Mr. Eastman to see whether he could come over to the hotel to help Mr. Trump’s team.

Mr. Eastman said he was only in the room for 15 minutes before being ushered out — but it was long enough, he said, for him to catch Covid-19 there, and he became ill for several weeks. By the time he felt better, it was the beginning of December — when Mr. Trump called to see whether Mr. Eastman could help bring legal action directly before the Supreme Court. In the days that followed, Mr. Eastman filed two briefs with the Supreme Court on Mr. Trump’s behalf, but those efforts quickly failed.

Mr. Trump remained undeterred. On Christmas Eve, while Mr. Eastman was with his family in Texas, a Trump aide reached out to him about writing a memo about the Jan. 6 certification. Mr. Eastman wrote what became the two-page outline asserting the vice president’s power to hold up the certification, and then a lengthier memo, which he circulated to Mr. Trump’s legal team several days later.

Shortly after New Year’s Day, the White House called Mr. Eastman and asked him to fly to Washington to meet with Mr. Trump and Mr. Pence. Mr. Pence’s chief of staff, Marc Short, and Mr. Pence’s legal counsel, Greg Jacob, first met with Mr. Eastman, giving them a sense of what Mr. Eastman was planning to argue to Mr. Trump in their meeting with the president the next day, Jan. 4.

In that subsequent meeting with Mr. Trump and Mr. Pence, Mr. Eastman was the only adviser to the president in the room.

“It started with the president talking about how some of the legal scholarship that had been done, saying under the 12th amendment, the vice president has the ultimate authority to reject invalid electoral votes and he asked me what I thought about it,” Mr. Eastman said.

“It’s a little bit more complicated than that, that’s certainly one of the arguments that’s been put out there, it’s never been tested,” Mr. Eastman said he replied.

Mr. Eastman said that Mr. Pence then turned to him and asked, “Do you think I have such power?”

Mr. Eastman said he told Mr. Pence that he might have the power, but that it would be foolish for him to exercise it until state legislatures certified a new set of electors for Mr. Trump — something that had not happened.

A person close to Mr. Pence, who was not authorized to speak publicly about the Oval Office conversation, said that Mr. Eastman acknowledged that the vice president most likely did not have that power, at which point Mr. Pence turned to Mr. Trump and said, “Did you hear that, Mr. President?”

Mr. Trump appeared to be only half-listening, the person said.

Mr. Eastman said he then pivoted the conversation to asking Mr. Pence to delay the certification.

“What we asked him to do was delay the proceedings at the request of these state legislatures so they could look into the matter,” Mr. Eastman said.

Mr. Eastman recounted that Mr. Pence said he “would take it under advisement,” but Mr. Eastman said he did not believe Mr. Pence would go along with it.

“The delay was kind of new to him,” Mr. Eastman said about Mr. Pence, “and he wanted to think about it over and meet with his staff about it. But I didn’t think he would do it. My sense was he knew an irretrievable break with Trump was about to come, and he was trying to delay that uncomfortable moment for as long as he could.”

Mr. Eastman recalled getting in touch with Mr. Pence’s legal counsel Mr. Jacob the next day about whether Mr. Pence could delay the certification.

“I think Jacob was looking for a way for he and Pence to be convinced to take the action that we were requesting, and so I think he continued to meet with me and push back on the arguments and hear my counters, what have you, to try and see whether they could reconcile themselves to what the president had asked,” Mr. Eastman said.

After a final rebuff from Mr. Pence — and shortly before an angry mob stormed the Capitol on Jan. 6 — Mr. Eastman took to the stage at Mr. Trump’s televised rally on the Ellipse near the White House to cheers, pushing false claims about election fraud and calling once more for a delay in the certification.

“We no longer live in a self-governing republic if we can’t get the answer to this question,” Mr. Eastman said. “This is bigger than President Trump! It is the very essence of our republican form of government and it has to be done!”

Matthew Cullen contributed research.