The Electoral Count Act is both a legal monstrosity and a fascinating puzzle.

Intended to settle disputes about how America chooses its presidents, the 135-year-old law has arguably done the opposite. Last year, its poorly written and ambiguous text tempted Donald Trump into trying to overturn Joe Biden’s victory, using a fringe legal theory that his own vice president rejected.

Scholars say the law remains a ticking time bomb. And with Trump on their minds, members of Congress in both parties now agree that fixing it before the 2024 election is a matter of national urgency.

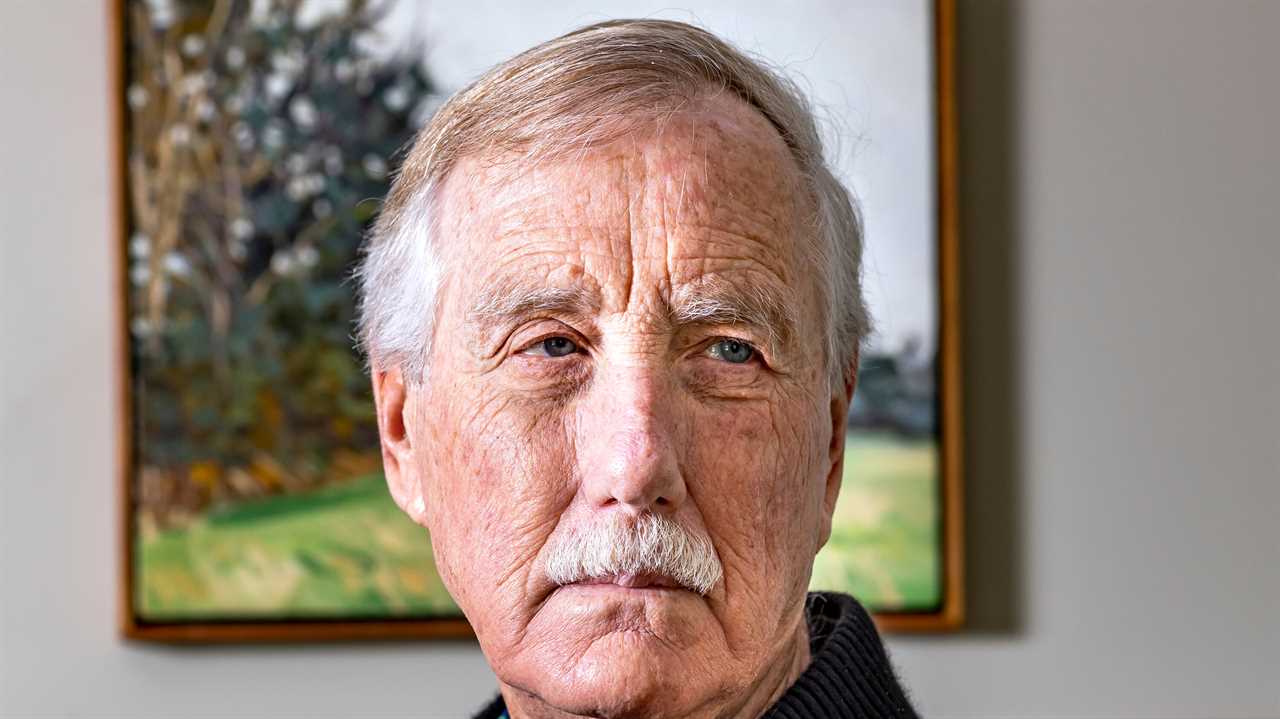

“If people don’t trust elections as a fair way to transition power, then what are you left with?” said Senator Angus King, an independent from Maine who has been leading the reform efforts. “I would argue that Jan. 6 is a harbinger.”

‘Unsavory’ origins

The Electoral Count Act’s origins are, as King put it, “unsavory.”

More than a decade elapsed between the disputed election that inspired it and its passage in 1887. Under the bargain that ended that dispute, the Republican candidate, Rutherford B. Hayes, agreed to withdraw federal troops from the occupied South — effectively ending Reconstruction and launching the Jim Crow era.

The law itself is a morass of archaic and confusing language. One especially baffling sentence in Section 15 — which lays out what is meant to happen when Congress counts the votes on Jan. 6 — is 275 words long and contains 21 commas and two semicolons.

Amy Lynn Hess, the author of a grammatical textbook on diagraming sentences, told us that mapping out that one sentence alone would take about six hours and require a large piece of paper.

“It’s one of the most confusing pieces of legislation I’ve ever read,” King told us. “It’s impossible to figure out exactly what they intended.”

King has been working through how to fix the Electoral Count Act since the spring, when he first started sounding the alarm about its deficiencies. His office has become a hub of expertise on the subject.

“It just so happens I have a political science Ph.D. on my staff,” King said. “And when I assigned him to start working on this, it was like heaven for him.”

Last week, King and two Democratic colleagues, Senators Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota and Dick Durbin of Illinois, introduced a draft discussion bill aimed at addressing the act’s main weaknesses.

King said he hopes it will serve as “a head start” for more than a dozen senators in both parties who have been meeting to hash out legislation of their own.

One leader of that effort, Senator Joe Manchin III of West Virginia, a Democrat, vowed on Sunday that a reform bill “absolutely” will pass. Senator Lisa Murkowski, a Republican of Alaska, said the lawmakers were taking “the Goldilocks approach” — as in, “we’re going to try to find what’s just right.”

But finding a compromise that will satisfy both progressive Democrats and the 10 Republican senators required for passage in the Senate won’t be easy. Already, differences have emerged over what role the federal courts should play in adjudicating election disputes within states, according to people close to the talks.

Mr. Worst-Case Scenario

Few have studied the Electoral Count Act more obsessively than Matthew Seligman, a fellow at Yale Law School.

In an exhaustive 100-page paper, he walked through nearly every combination of scenarios for how the law could be abused by partisans bent on stretching its boundaries to the max. And what he discovered shocked him.

“Its underexplored weaknesses are so profound that they could result in an even more explosive conflict in 2024 and beyond, fueled by increasingly vitriolic political polarization and constitutional hardball,” Seligman warns.

He found, for instance, that in nine of the 34 presidential elections since 1887, “the losing party could have reversed the results of the presidential election and the party that won legitimately would have been powerless to stop it.”

Seligman refrained from publishing his paper for more than five years, out of fear that it could be used for malicious ends. He worries especially about what he calls the “governor’s tiebreaker,” a loophole in the existing law that, if abused, could cause a constitutional crisis.

Suppose that on Jan. 6, 2025 — the next time the Electoral Count Act will come into play — Republicans control the House of Representatives and the governorship of Georgia.

Seligman conjures a hypothetical yet plausible scenario: The secretary of state declares that President Biden won the popular vote in the state. But Gov. David Perdue, who has said he believes the 2020 election was stolen, declares there was “fraud” and submits a slate of Trump electors to Congress instead. Then the House, led by Speaker Kevin McCarthy, certifies Trump as the winner.

Even if Democrats controlled the Senate and rejected Perdue’s electoral slate, it wouldn’t matter, Seligman said. Because of the quirks of the Electoral Count Act, Georgia’s 16 Electoral College votes would go for Trump.

“When you’re in this era of pervasive distrust, you start running through all these rabbit holes,” said Richard H. Pildes, a professor at New York University’s School of Law. “We haven’t had to chase down so many rabbit holes before.”

Now, for the hard part

The easiest part in fixing the Electoral Count Act, according to half a dozen experts who have studied the issue, would be figuring out how Congress would accept the results from the states.

There’s wide agreement on three points to do that:

Extending the safe harbor deadline, the date by which all challenges to a state’s election results must be completed.

Clarifying that the role of the vice president on Jan. 6 is purely “ministerial,” meaning the vice president merely opens the envelopes and has no power to reject electors.

Raising the number of members of Congress needed to object to a state’s electors; currently, one lawmaker from each chamber is enough to do so.

The harder part is figuring out how to clarify the process for how states choose their electors in the first place. And that’s where things get tricky.

The states that decide presidential elections are often closely divided. Maybe one party controls the legislature while another holds the governor’s mansion or the secretary of state’s office. And while each state has its own rules for working through any election disputes, it’s not always clear what is supposed to happen.

In Michigan, for instance, a canvassing board made up of an equal number of Republicans and Democrats certifies the state’s election results. What if they can’t reach a decision? That nearly happened in 2020, until one Republican member broke with his party and declared Biden the winner.

Progressive Democrats will want more aggressive provisions to prevent attempts in Republican-led states to subvert the results. Republicans will fear a slippery slope and try to keep the bill as narrow as possible.

King’s solution was to clarify the process for the federal courts to referee disputes between, say, a governor and a secretary of state, and to require states to hash out their internal disagreements by the federal “safe harbor date,” which he would push back to Dec. 20 instead of its current date of Dec. 8.

The political obstacles are formidable, too. Still reeling from their failure to pass federal voting rights legislation, many Democrats are suspicious of Republicans’ motives. It’s entirely possible that Democrats will decide that it’s better to do nothing, because passing a bipartisan bill to fix the Electoral Count Act would allow Mitch McConnell, the Republican Senate minority leader, to portray himself as the savior of American democracy.

Representative Zoe Lofgren, a California Democrat who heads the Committee on House Administration, has been working with Representative Liz Cheney, the Wyoming Republican, on a bipartisan House bill. But she stressed that their ambitions are fairly limited.

“We’ve made clear this is no substitute for the voting rights bill,” Lofgren told us. “The fact that the Senate failed on that shouldn’t be an excuse for not doing something modest.”

What to read tonight

Jill Biden, the first lady, told community college leaders that her effort to provide two years of free community college isn’t in Democrats’ social spending bill, Katie Rogers reports.

Republican campaigns have intensified their attacks on Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, a trend that Sheryl Gay Stolberg described as representative of “the deep schism in the country, mistrust in government and a brewing populist resentment of the elites, all made worse by the pandemic.”

Peter Thiel is stepping down from the board of Meta, according to its parent company, Facebook. Ryan Mac and Mike Isaac hear that Thiel, who has become one of the Republican Party’s largest donors, wants to focus his energy on the midterms instead.

Chief Justice John G. Roberts joined the three liberal members’ dissent to a Supreme Court order reinstating an Alabama congressional map. A lower court had ruled that the map violated the Voting Rights Act, Adam Liptak reports.

STATESIDE

Voting rights push goes local

Arizona, as we’ve noted, has become a hotly contested battleground, and the two parties have clashed continuously over the rules that govern how elections can and should be held. Just last week, the Republican speaker of the State House spiked a bill that would have allowed the Legislature to reject election results it didn’t like.

A new ballot initiative led by Arizonans for Fair Elections, a nonprofit advocacy group, would do the opposite: expand voter registration, extend in-person early voting and guard against partisan purges of the voter rolls, along with a host of other changes that groups on the left have long wanted.

It would essentially overturn an existing law that was litigated all the way to the Supreme Court last year, resulting in a 6-3 decision favoring the Republican attorney general. Arizonans for Fair Elections expects to announce its plans on Tuesday.

The move comes at a time of frustration for voting rights advocates, whose push for legislation to enact similar changes at the federal level ran into a wall of Republican opposition.

Will the local approach fare any better? A citizens’ initiative that passed in 2000 established Arizona’s independent redistricting commission, so there’s a precedent. To get on the ballot this year, the group needs to obtain 237,645 valid signatures by July 7.

“Our Legislature for many years has been trying to chip away at the right to vote,” said Joel Edman, a spokesman for the initiative. “We’re at a big moment for our democracy.”