WASHINGTON — A day after the House impeached President Trump for inciting a violent insurrection at the Capitol, Democrats and Republicans in the Senate were developing plans on Thursday to try the departing president at the same time as they begin considering the agenda of the incoming one.

Democrats, poised to take unified power in Washington next week for the first time in a decade, worked with Republican leaders to try to find a proposal to allow the Senate to split time between the impeachment trial of Mr. Trump and consideration of President-elect Joseph R. Biden Jr.’s cabinet nominees and his $1.9 trillion economic recovery plan to address the coronavirus.

“It’s far from ideal, no question,” said Senator Richard Blumenthal, Democrat of Connecticut. But, he said, “a dual track is perfectly doable if there is a will to make it happen.”

He said a trial would be straightforward.

“The evidence is Trump’s own words, recorded on video,” Mr. Blumenthal said. “It’s a question of whether Republicans want to step up and face history.”

Although Senator Mitch McConnell, Republican of Kentucky and the majority leader, has privately told advisers that he approves of the impeachment drive and believes it could help his party purge itself of Mr. Trump, he refused to begin the proceedings this week while he is still in charge. That means the trial will not effectively start until after Mr. Biden is sworn in on Wednesday, officials involved in the planning said.

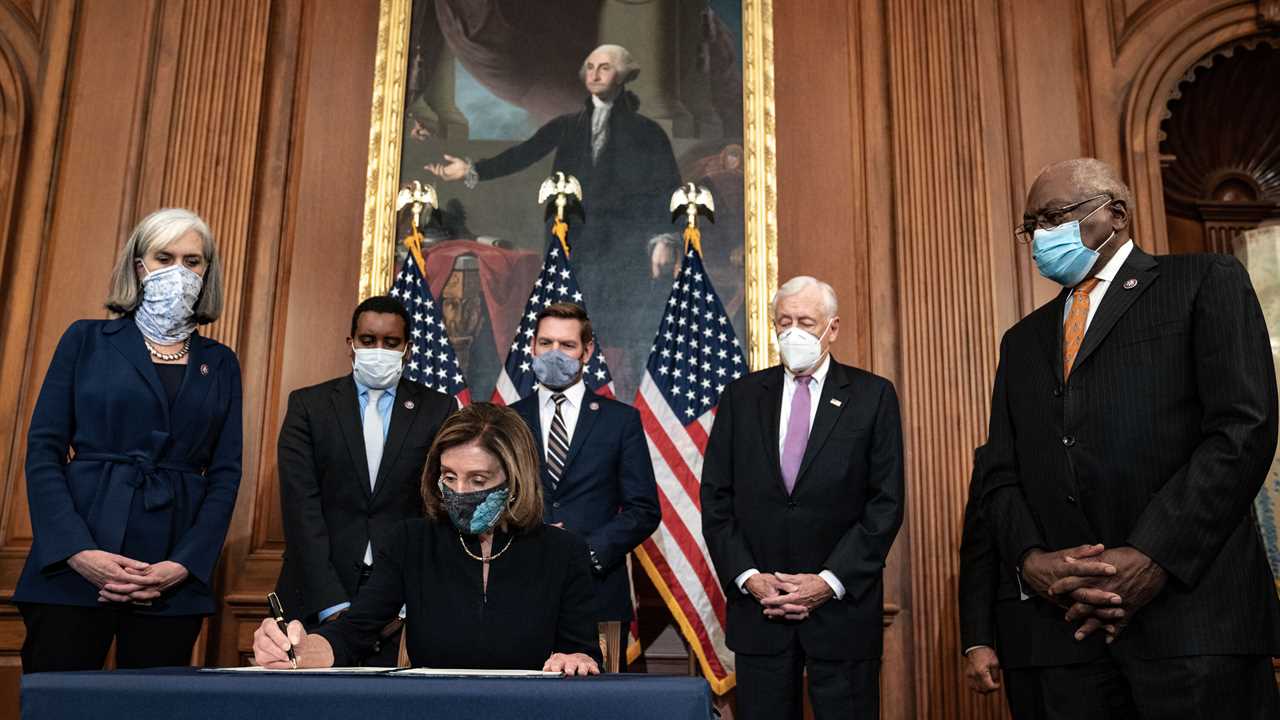

Speaker Nancy Pelosi of California has discretion over when to transmit the article of impeachment, formally initiating the Senate proceeding. Some Democrats said she might wait until Monday, Jan. 25, or longer to allow more time for the Senate to put in place Mr. Biden’s national security team to respond to continued threats of violence from pro-Trump extremists.

With Republicans fractured after the president’s bid to overturn the election inspired a rampage, many of them were trying to gauge the dynamics of a vote to convict Mr. Trump. Doing so would open the door to disqualifying him from holding office in the future.

A cautionary tale was playing out in the House, where a faction of Mr. Trump’s most ardent allies was working to topple Representative Liz Cheney of Wyoming, the No. 3 Republican, from her leadership post. Ms. Cheney had joined nine other members of the party who voted with Democrats to charge the president with “incitement of insurrection.”

Most Senate Republicans stayed publicly silent about their positions. But Senator Lisa Murkowski, Republican of Alaska and one of the president’s leading critics, signaled on Thursday that she was among a small group in her party so far considering convicting Mr. Trump. In a stinging statement, she called his actions “unlawful,” saying they warranted consequences, and added that the House had acted appropriately in impeaching him.

Though she did not commit to finding the president guilty, saying she would listen carefully to the arguments on both sides, she strongly suggested that she was inclined to do so.

“On the day of the riots, President Trump’s words incited violence, which led to the injury and deaths of Americans — including a Capitol Police officer — the desecration of the Capitol, and briefly interfered with the government’s ability to ensure a peaceful transfer of power,” Ms. Murkowski said.

Ms. Murkowski joined a small group of other Republicans — including Senators Ben Sasse of Nebraska, Mitt Romney of Utah, Patrick J. Toomey of Pennsylvania and Susan Collins of Maine — who have said they hold the president responsible for the siege and will weigh the impeachment charge. Mr. Romney was the only Republican last year to vote to convict Mr. Trump when the House impeached him for pressuring Ukraine to incriminate Mr. Biden.

Mr. McConnell has indicated to colleagues that he is undecided about whether to convict Mr. Trump — a stark departure from his outspoken opposition last year to the House’s first impeachment case. He told advisers that he believed the president committed impeachable offenses, though he, too, wanted to hear the arguments at trial.

But it remained unclear whether the 17 Republican senators whose votes would be needed to convict Mr. Trump by the requisite two-thirds majority would agree to find him guilty. Senator Lindsey Graham, Republican of South Carolina, worked feverishly to whip up opposition to a conviction, arguing that it would only further inflame a dangerously divided nation.

With Mr. McConnell sending mixed signals about where he would come down, Republican strategists and senior aides on Capitol Hill believed he could ultimately swing the result one way or another.

If the Senate did convict, it could proceed to disqualify Mr. Trump from holding office again with only a simple majority vote, a prospect motivating some on both sides.

Senators considering breaking with the president needed to look no further than Ms. Cheney to understand the risks.

In a petition being privately circulated among Republicans on Capitol Hill, a group of lawmakers led by Representatives Andy Biggs of Arizona, the chairman of the ultraconservative Freedom Caucus, and Matt Rosendale of Montana, claimed that Ms. Cheney’s vote to impeach the president had “brought the conference into disrepute and produced discord.” It noted that as they argued in favor of charging Mr. Trump on Wednesday, Democrats had cited Ms. Cheney’s support for impeachment “multiple times.”

“One of those 10 cannot be our leader,” Representative Matt Gaetz, Republican of Florida, said Wednesday evening in an interview on Fox News’s “Hannity,” referring to the group of Republicans who voted to impeach Mr. Trump. “It is untenable, unsustainable, and we need to make a leadership change.”

Calling hers a “vote of conscience,” Ms. Cheney brushed aside calls to step down on Wednesday, saying, “I’m not going anywhere.” An unlikely group of hawkish traditionalists and conservative hard-liners have rushed to defend her.