WASHINGTON — After four years of enabling and appeasing President Trump, Republicans find themselves at the end of his tenure in exactly the place they had so desperately tried to avoid: a toxic internecine brawl over his conduct and character that could badly damage their party.

With their Senate power on the line in Georgia in two days, Republicans entered the new Congress on Sunday bitterly divided over the basic question of whether to acknowledge the reality that Mr. Trump had lost the election, or to abet his unjustified and increasingly brazen attempts to overturn the results.

The extraordinary conflict among congressional Republicans reflects the dilemma they face after four years of acquiescence to Mr. Trump’s whims and silence in the face of his most outrageous actions. Now that the president has escalated his demands to subvert an election, they are confronting a litmus test involving democracy itself, keenly aware that many voters could punish them for failing to back Mr. Trump.

The rift has thrust Republicans — who typically try to minimize their differences in public — into an intramural battle more pronounced than any other of the Trump era before what would normally be a routine joint session on Wednesday to certify President-elect Joseph R. Biden Jr.’s victory. Top party officials, including the top two Senate leaders and the No. 3 House Republican, quietly pushed back against what all sides conceded would be a futile effort — though one that has the backing of a growing segment of the party — to reject the results.

Others spoke out publicly against the instigators of the move to invalidate Mr. Biden’s win, accusing them of putting political ambition before the nation’s interest.

“Efforts to reject the votes of the Electoral College and sow doubt about Joe Biden’s victory strike at the foundation of our Republic,” Paul D. Ryan, the former House speaker and Republican from Wisconsin, said in a statement on Sunday. “It is difficult to conceive of a more anti-democratic and anti-conservative act than a federal intervention to overturn the results of state-certified elections and disenfranchise millions of Americans.”

Representative Liz Cheney, the third-ranking Republican, circulated a lengthy memo calling the move “exceptionally dangerous.”

As the clash unfolded, newly disclosed recordings of Mr. Trump trying to pressure state officials in Georgia to reverse his loss there reflected how intent he was on finding enough votes to cling to power and what little regard he had for the fortunes of his party, whose Senate majority hangs on the outcome of two runoffs in the state on Tuesday.

During the conversation on Saturday, a recording of which was obtained earlier by The Washington Post, Mr. Trump never mentioned Senators David Perdue and Kelly Loeffler, except to threaten Brad Raffensperger, Georgia’s Republican secretary of state, that if he failed to find more votes for the president by Tuesday, “you’re going to have people just not voting” in the runoff contests. Mr. Trump is scheduled to campaign in the state on Monday.

Most Republicans were mum on Sunday about the revelations, though Representative Adam Kinzinger of Illinois, a frequent critic of Mr. Trump, called it “absolutely appalling.”

“To every member of Congress considering objecting to the election results, you cannot — in light of this — do so with a clean conscience,” Mr. Kinzinger wrote on Twitter, appending the hashtag #RestoreOurGOP.

Beyond Georgia, the Republican dilemma had implications for the ability of party members to work with one another and a new Democratic White House after Jan. 20, for Republicans on the midterm ballot in 2022 and for the party’s presidential field in 2024.

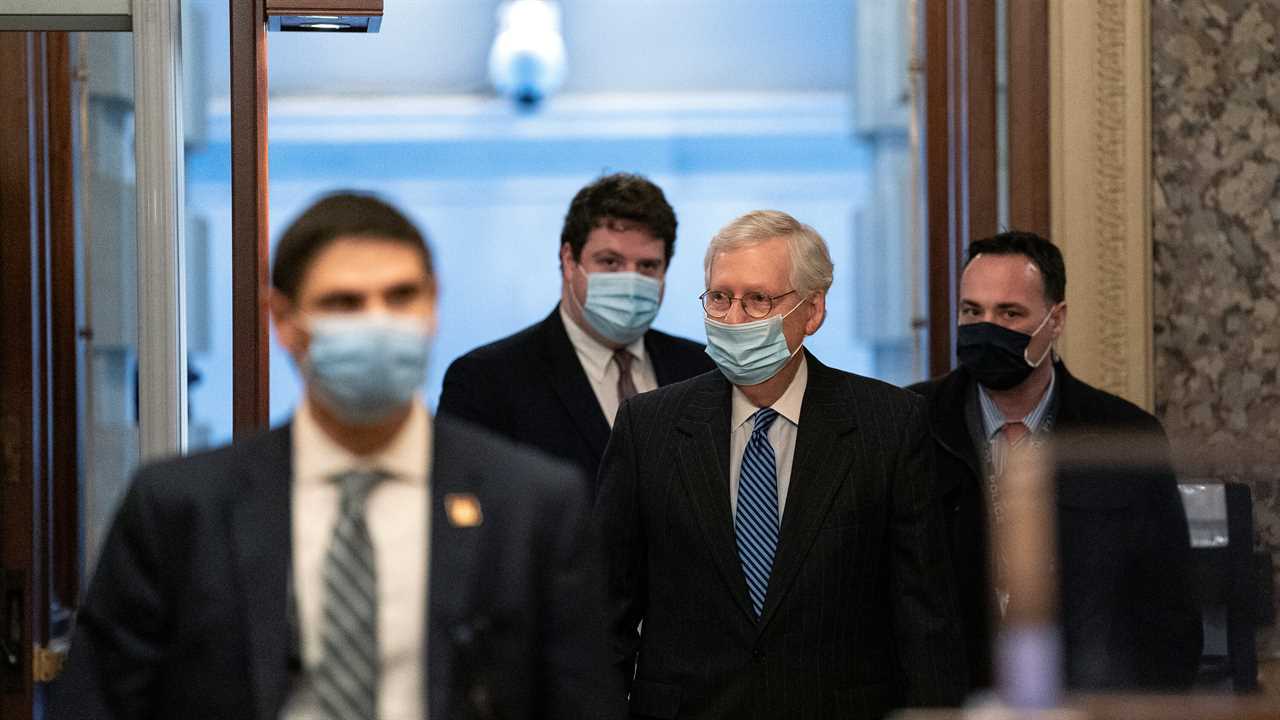

It was a situation that Senator Mitch McConnell, Republican of Kentucky and the majority leader for at least a few more days, had assiduously sought to avoid.

He has worked feverishly to maneuver his party around Mr. Trump’s outbursts and outrages since January 2017, hoping to reap the political and policy benefits of having a mercurial ally in the White House without having to pay too high a price. The bargain delivered him a personal legacy of 234 conservative judges along with business-friendly federal policies prized by Republicans. Mr. McConnell even delayed the traditional recognition of the presidential winner — a man he has known for decades and considers a friend — to mollify Mr. Trump until it became untenable with the initial tally of electoral votes on Dec. 14.

It was still not enough for Mr. Trump, who made clear that he expected Republicans to join him first in sowing doubt about the election results and ultimately in moving to overturn them.

In a pointed challenge to Mr. McConnell’s influence and authority at the outset of Congress, a dozen Senate Republicans rejected his plea to not contest the tabulating of the electoral votes in the House on Wednesday. They announced that they would join scores of House Republicans in challenging the electoral count, forcing members of their party to side with either Mr. Trump or Mr. Biden in a move that is almost certain to fail even as it sows deep discord. Among those planning to try to reverse the count were four incoming Republican senators whose first official act was to announce that they would challenge the integrity of the vote that brought them to Washington.

“I think the people of Kansas feel disenfranchised, and they want us to follow through on the many irregularities they saw,” said Senator-elect Roger Marshall, Republican of Kansas. “We want our day in court.”

Judges across the country, and a Supreme Court with a conservative majority, have rejected nearly 60 attempts by Mr. Trump and his allies to challenge the results.

The looming showdown over the electoral votes, along with attendance restrictions because of the coronavirus pandemic, cast a pall over the first day of the new Congress, typically a celebratory affair with throngs of family and friends packing the hallways and spectator galleries for the swearing-in of new members and celebrations around Capitol Hill. Instead, in an unusual weekend session that was the first time a new Congress had convened on a Sunday, the Capitol was quiet as the dispute over the election hung over the opening proceedings and dashed any hope for a fresh start in 2021.

In her 21-page memo, Ms. Cheney refuted allegations of widespread election irregularities, recounted the litany of court findings against the president and warned fellow Republicans that they were making a serious mistake.

“Such objections set an exceptionally dangerous precedent, threatening to steal states’ explicit constitutional responsibility for choosing the president and bestowing it instead on Congress,” her memo said. “This is directly at odds with the Constitution’s clear text and our core beliefs as Republicans.”

“It undermines the public’s faith in the integrity of our elections,” warned Senator Susan Collins, Republican of Maine, who was sworn in for a fifth term on Sunday.

Other Republicans said the call by senators challenging the election for a special commission to “audit” results in swing states within 10 days was ill-conceived and unworkable.

“Proposing a commission at this late date — which has zero chance of becoming reality — is not effectively fighting for President Trump,” said Senator Lindsey Graham, Republican of South Carolina and a top ally of the president. He said those disputing the election results would have “a high bar to clear” in persuading him to back them.

But those planning to try to upend Mr. Biden’s victory said they were exercising their independence and acting in the interests of constituents who were demanding answers to questions raised by Mr. Trump and his allies about election malfeasance — charges that have been widely dismissed.

“There are lots of folks in my state that still want those answers to come out,” said Senator James Lankford, Republican of Oklahoma, who pointed to “all these different questions that are hanging out there.”

He and other Republicans said they were acting no differently than Democrats had in 2005, when then-Senator Barbara Boxer of California challenged electors for President George W. Bush. But in that case, John Kerry, the Democratic nominee, had conceded and was not actively instigating efforts to reverse the results.

Republicans trying to hold their majority with victories in Georgia were particularly worried about the risks the fight might hold for their candidates facing voters in two years, when incumbent Republicans such as Senators Roy Blunt of Missouri, Rob Portman of Ohio and Lisa Murkowski of Alaska could face primary challenges from the right if they refuse to support the attempt to overturn the election. Given the Democratic majority in the House and the fact that enough Republicans have made clear that they would join Democrats in holding off the challenge in the Senate, Mr. McConnell and others view the effort to bolster the president as both risky and doomed to failure.

In opening the new session of the Senate, Mr. McConnell did not directly address the fight, but he alluded to it, conceding that there were “plenty of disagreements and policy differences among our ranks.”

Democrats were watching the unfolding spectacle with outrage and a sense of foreboding over the future implications. But they expressed certainty of the outcome.

“Look, they can do whatever they want,” said Senator Chuck Schumer of New York, the Democratic leader. “On Jan. 20, Joe Biden will be president and Kamala Harris will be vice president no matter what they try to do.”

“I think they are hurting themselves and hurting the democracy,” he added, “all to try to please somebody who has no fidelity to elections or even the truth.”