WASHINGTON — Justice Stephen G. Breyer’s successor at the Supreme Court may turn out to possess a blazing intellect, infectious charm and fresh liberal perspectives. But there is no reason to think the new justice will be able to slow the court’s accelerating drive to the right.

Indeed, the court’s trajectory may have figured in Justice Breyer’s retirement calculations, said Kate Shaw, a professor at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law. “There’s a good chance,” she said, “that the dynamics on the current court — both the speed and magnitude of the change that’s coming — had some impact on Breyer’s decision to go now.”

He may have figured, she suggested, that someone else might as well try to stand in the way of a juggernaut committed to fulfilling, and fast, the conservative legal movement’s wish list in cases on abortion, guns, race, religion and voting.

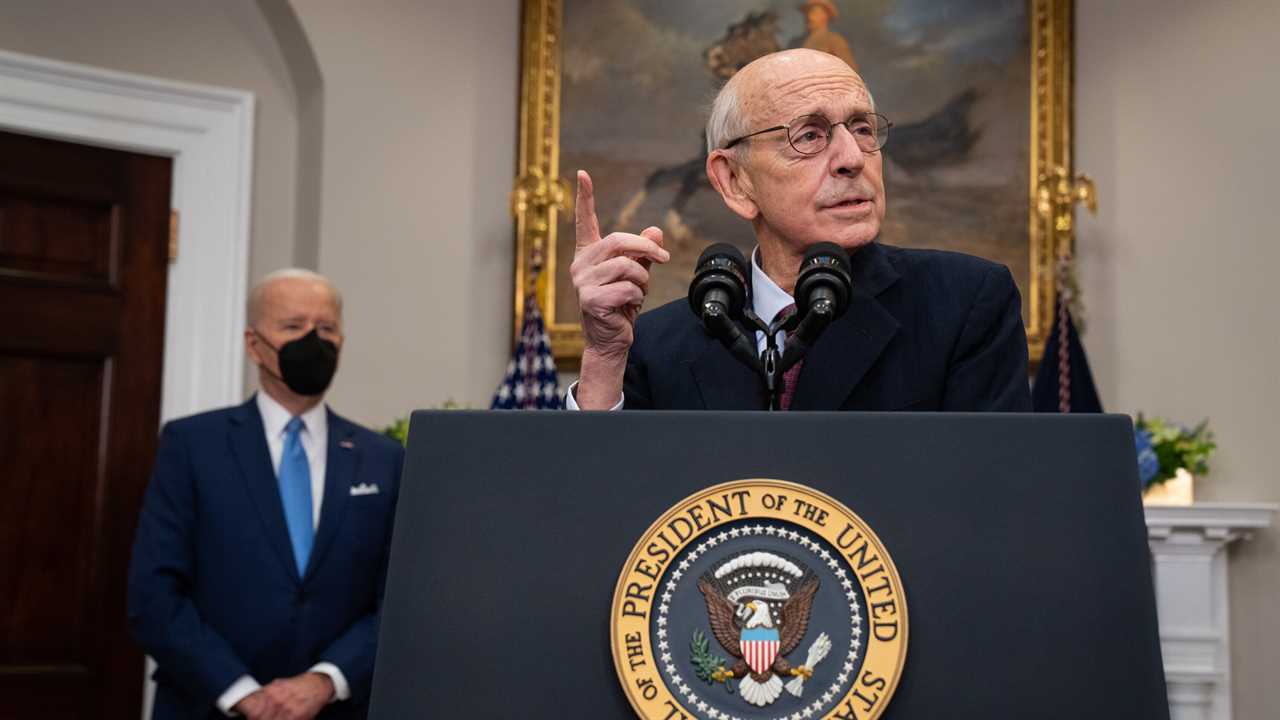

In a letter to President Biden on Thursday, Justice Breyer, 83, said he would step down at the end of the Supreme Court’s current term, in June or July, if his successor has been confirmed by then. But that liberal-for-liberal swap will do nothing to alter the power and ambitions of the court’s six-member conservative supermajority.

Its members, all appointed by Republican presidents, seem largely unconcerned about a sharp dip in the court’s public approval, caustic criticism from the liberal justices or the possibility that Congress could add seats or otherwise alter the court’s structure. Facing no perceived headwinds, the conservative majority seems ready to go for broke.

“This is a court in a hurry,” said Stephen I. Vladeck, a law professor at the University of Texas at Austin.

The shape and speed of the court’s conservative agenda have come into focus in the last six months.

Most notably, the court repeatedly refused to block a Texas law that bans most abortions after six weeks. The law is flatly at odds with Roe v. Wade, the 1973 decision that established a constitutional right to abortion and prohibited states from banning the procedure until fetal viability, around 23 weeks.

The court also repeatedly thwarted initiatives by the Biden administration to address the coronavirus pandemic, blocking an eviction moratorium and a vaccine-or-testing mandate for large employers. And it refused to block a lower-court ruling requiring the administration to reinstate a Trump-era immigration program that forces asylum seekers arriving at the southwestern border to await approval in Mexico.

Although there was no split in the lower courts, the usual key criterion for Supreme Court review, the justices agreed to decide whether to overrule Roe entirely in a case from Mississippi and whether to do away with affirmative action in higher education in cases concerning Harvard and the University of North Carolina. In that last case, the appeals court had not even ruled yet.

It is no surprise that conservative justices vote for conservative outcomes. But the pace of change, often accompanied by procedural shortcuts, is harder to explain.

The three newest justices, all appointed by President Donald J. Trump, are 50 to 56 years old. If they serve as long as Justice Breyer, they will be on the court for another quarter-century or so. They have plenty of time.

Nor do there seem to be looming departures among the other conservatives. The oldest, Justice Clarence Thomas, is 73, a decade younger than Justice Breyer, and lately, he has been particularly engaged in the court’s work.

He has been an active participant in oral arguments, for instance, a change from earlier in his tenure, when he once went for a decade without asking a question from the bench.

The six-justice conservative majority seems built to last.

Still, two of the last four vacancies at the court were created by deaths — those of Justice Antonin Scalia in 2016 and Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in 2020.

“Maybe there’s some sense that these majorities can be fleeting,” Professor Shaw said, “so you do as much as you can as quickly as you can because who knows what the future holds.”

When the case on overruling Roe was argued in December, the court’s three liberal members sounded dismayed if not distraught at the prospect of such a stark shift so soon after a change in the court’s membership. Justice Ginsburg, a liberal icon, was replaced by a conservative, Justice Amy Coney Barrett, Mr. Trump’s third appointee to the court.

“Will this institution survive the stench that this creates in the public perception that the Constitution and its reading are just political acts?” Justice Sonia Sotomayor asked.

The court’s conservative wing seemed unmoved. Indeed, its five most conservative members seemed to have little interest in a more incremental position sketched out by Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr., who suggested that the court could uphold the Mississippi law at issue, which bans most abortions after 15 weeks, and leave it at that for now.

Professor Shaw said some members of the court may have been emboldened by the lack of a sustained national outcry over the Texas abortion law.

“They’ve dipped their toe in the water of essentially ending Roe in the second-most populous state in the nation,” she said. “They may well have drawn the conclusion that any backlash to the overruling of Roe would be somewhat muted or short-lived and would not create an existential threat to the court.”

The inconclusive report issued by Mr. Biden’s commission on potential changes to the court’s processes and structure may also have given the court’s conservative majority confidence that it had nothing to fear from the other branches.

“When the Biden commission came back with its report, that just further took the brakes off,” Professor Vladeck said. “This is not 1937.”

That was the year that President Franklin D. Roosevelt introduced what came to be known as his court-packing plan. It failed in the immediate sense: The number of justices stayed steady at nine. But it seemed to exert pressure on the court, which began to uphold progressive New Deal legislation.

There appears to be no comparable pressure now, Professor Vladeck said. “This is a court that is not shy, that is not afraid of its shadow and is not remotely worried about doing anything to provoke Congress,” he said.

The court has lately been creative in using unusual procedures to generate fast results.

In recent years, for instance, it has done some of its most important work on what critics call its shadow docket, in which the court decides emergency applications on a very quick schedule without full briefing and oral argument, often in a terse ruling issued late at night.

Probably in response to criticism of that practice, the court has this term started to hear arguments in important cases that had arrived at the court as emergency applications, including ones on the death penalty, the Texas abortion law and two Biden administration programs requiring or encouraging vaccination against the coronavirus.

The court has also begun to use another procedural device to allow it to rule quickly, agreeing to hear cases before appeals courts have even issued decisions.

The procedure, “certiorari before judgment,” used to be exceedingly rare, seemingly reserved for national crises like President Richard M. Nixon’s refusal to turn over tape recordings to a special prosecutor or President Harry S. Truman’s seizure of the steel industry.

Until early 2019, the court had not used the procedure in 14 years. Since then, Professor Vladeck found, it has used it 14 times.

“This is a court that is not afraid of dusting off obscure procedures and disfavored paths to review,” he said, if that allows it to reach decisions more quickly.

“It all ends up in the same place,” he said, “which is increasing the power of the court.”