More than 30 years ago, Robert Reives Sr. marched into a meeting of his county government in Sanford, N.C., with a demand: Create a predominantly Black district in the county, which was 23 percent Black at the time but had no Black representation, or face a lawsuit under the Voting Rights Act.

The county commission refused, and Mr. Reives prepared to sue. But after the county settled and redrew its districts, he was elected in 1990 as Lee County’s first Black commissioner, a post he has held comfortably ever since.

Until this year.

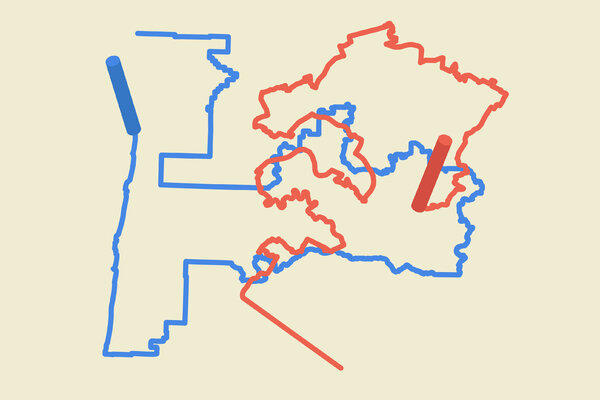

Republicans, newly in power and in control of the redrawing of county maps, extended the district to the northeast, adding more rural and suburban white voters to the mostly rural district southwest of Raleigh and effectively diluting the influence of its Black voters. Mr. Reives, who is still the county’s only Black commissioner, fears he will now lose his seat.

“They all have the same objective,” he said in an interview, referring to local Republican officials. “To get me out of the seat.”

Mr. Reives is one of a growing number of Black elected officials across the country — ranging from members of Congress to county commissioners — who have been drawn out of their districts, placed in newly competitive districts or bundled into new districts where they must vie against incumbents from their own party.

Almost all of the affected lawmakers are Democrats, and most of the mapmakers are white Republicans. The G.O.P. is currently seeking to widen its advantage in states including North Carolina, Ohio, Georgia and Texas, and because partisan gerrymandering has long been difficult to disentangle from racial gerrymandering, proving the motive can be troublesome.

But the effect remains the same: less political power for communities of color.

The pattern has grown more pronounced during this year’s redistricting cycle, the first since the Supreme Court struck down the heart of the Voting Rights Act in 2013 and allowed jurisdictions with a history of voting discrimination to pass election laws and draw political maps without approval from the Justice Department.

How Maps Reshape American Politics

We answer your most pressing questions about redistricting and gerrymandering.

“Let’s call it a five-alarm fire,” G.K. Butterfield, a Black congressman from North Carolina, said of the current round of congressional redistricting. He is retiring next year after Republicans removed Pitt County, which is about 35 percent Black, from his district.

“I just didn’t see it coming,” he said in an interview. “I did not believe that they would go to that extreme.”

Redistricting at a Glance

Every 10 years, each state in the U.S is required to redraw the boundaries of their congressional and state legislative districts in a process known as redistricting.

- Redistricting, Explained: Answers to your most pressing questions about redistricting and gerrymandering.

- Breaking Down Texas’s Map: How redistricting efforts in Texas are working to make Republican districts even more red.

- G.O.P.’s Heavy Edge: Republicans are poised to capture enough seats to take the House in 2022, thanks to gerrymandering alone.

- Legal Options Dwindle: Persuading judges to undo skewed political maps was never easy. A shifting judicial landscape is making it harder.

A former chairman of the Congressional Black Caucus, Mr. Butterfield said fellow Black members of Congress were increasingly worried about the new Republican-drawn maps. “We are all rattled,” he said.

In addition to Mr. Butterfield, four Black state senators in North Carolina, five Black members of the state House of Representatives and several Black county officials have had their districts altered in ways that could cost them their seats. Nearly 24 hours after the maps were passed, civil rights groups sued the state.

Across the country, the precise number of elected officials of color who have had their districts changed in such ways is difficult to pinpoint. The New York Times identified more than two dozen of these officials, but there are probably significantly more in county and municipal districts. And whose seats are vulnerable or safe depends on a variety of factors, including the political environment at the time of elections.

But the number of Black legislators being drawn out of their districts outpaces that of recent redistricting cycles, when voting rights groups frequently found themselves in court trying to preserve existing majority-minority districts as often as they sought to create new ones.

“Without a doubt it’s worse than it was in any recent decade,” said Leah Aden, a deputy director of litigation at the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund Inc. “We have so much to contend with and it’s all happening very quickly.”

Republicans, who have vastly more control over redistricting nationally than Democrats do, defend their maps as legal and fair, giving a range of reasons.

Kirk Smith, the Republican chairman of Lee County’s board of commissioners, said that “to say only a person of a certain racial or ethnic group can represent only a person of the same racial or ethnic group has all the trappings of ethnocentric racism.”

In North Carolina and elsewhere, Republicans say that their new maps are race-blind, meaning officials used no racial data in designing the maps and therefore could not have drawn racially discriminatory districts because they had no idea where communities of color were.

“During the 2011 redistricting process, legislators considered race when drawing districts,” Ralph Hise, a Republican state senator in North Carolina, said in a statement. Through a spokesperson, he declined to answer specific questions, citing pending litigation.

His statement continued: “We were then sued for considering race and ordered to draw new districts. So during this process, legislators did not use any racial data when drawing districts, and we’re now being sued for not considering race.”

In other states, mapmakers have declined to add new districts with majorities of people of color even though the populations of minority residents have boomed. In Texas, where the population has increased by four million since the 2010 redistricting cycle, people of color account for more than 95 percent of the growth, but the State Legislature drew two new congressional seats with majority-white populations.

And in states like Alabama and South Carolina, Republican map drawers are continuing a decades-long tradition of packing nearly all of the Black voting-age population into a single congressional district, despite arguments from voters to create two separate districts. In Louisiana, Gov. John Bel Edwards, a Democrat, said on Thursday that the Republican-controlled State Legislature should draw a second majority-Black House district.

Allison Riggs, a co-executive director of the Southern Coalition for Social Justice, a civil rights group, said that the gerrymandering was “really an attack on Black voters, and the Black representatives are the visible outcome of that.”

Efforts to curb racial gerrymandering have been hampered by a 2019 Supreme Court decision, which ruled that partisan gerrymandering could not be challenged in federal court.

Though the court did leave intact Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, which prohibits racial gerrymandering, it offered no concrete guidance how to distinguish between a partisan gerrymander and a racial gerrymander when the result was both, such as in heavily Democratic Black communities.

Understand How U.S. Redistricting Works

What is redistricting? It’s the redrawing of the boundaries of congressional and state legislative districts. It happens every 10 years, after the census, to reflect changes in population.

Given that certain demographic groups have aligned tightly with political parties — 90 percent of Black voters in Georgia voted Democratic in 2020, for example — officials drawing gerrymandered maps could simply argue that politics were at play, not race.

In Georgia, another member of the Congressional Black Caucus, Representative Lucy McBath, has been drawn into a district with Representative Carolyn Bourdeaux, a fellow Democrat, setting up a competitive primary election.

In South Carolina, four Black Democrats in the state House of Representatives have been drawn into districts with fellow Democrats — compared with just one pair of white Republicans drawn into a district together.

J. Todd Rutherford, a Black Democrat from Columbia who serves as the minority leader of the state House of Representatives, said that maps proposed by the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund Inc. that would have maintained majority-Black districts would have been subject to their own gerrymandering objections because many of the state’s new residents were white retirees.

At the same time, he said, Democrats had to gerrymander legislative maps to maintain Black districts because of Black population losses in rural areas even as the number of white residents in the state surged. South Carolina Republicans, Mr. Rutherford said, exploited that population shift.

“It was extremely unsettling,” he said of the demographic changes. “The problem is there is simply no population in those areas. Those maps contorted themselves, and the Republicans in the majority shot them down.”

Worries are also spreading through Ohio’s state legislative Black caucus, which includes 19 state representatives and senators and which is one of the oldest Black caucuses in the nation.

Last month, Republicans in Ohio passed a gerrymandered map that locked in supermajorities in both chambers of the legislature, meaning Republicans would control more than two-thirds of seats even though former President Donald J. Trump won just 53 percent of Ohio voters in 2020.

At least four Black members of the state legislature had their districts altered or were drawn into another district. State Representative Juanita Brent, the vice president of the state legislative Black caucus, who has represented parts of Cleveland since 2019, was moved into a neighboring district.

“Putting Black Democrats against each other, or downsizing the amount of districts that people could run in, or moving people into a totally different district,” Ms. Brent said in an interview, “is trying to actually dilute the amount of representation that we have.”

State Senator Rob McColley, a Republican who sponsored the bill that established the new maps, did not respond to requests for comment. Previously, he has praised the new maps for keeping each of the state’s large cities in one Senate district.

“Not since the mid-60s have these seven major cities been whole, and, for the first time in more than 150 years, Cincinnati will be contained in a single district,” Mr. McColley said in a statement last month. “This is truly historic.”

But Ms. Brent said that keeping those cities in single districts amounted to a form of gerrymandering known as “packing,” which is frequently used to reduce the power of densely populated areas and which often prevents minority communities from increasing their representation.

“You are not really giving Cleveland a chance to have fair representation,” she said. “And Cleveland is a majority African American city.”