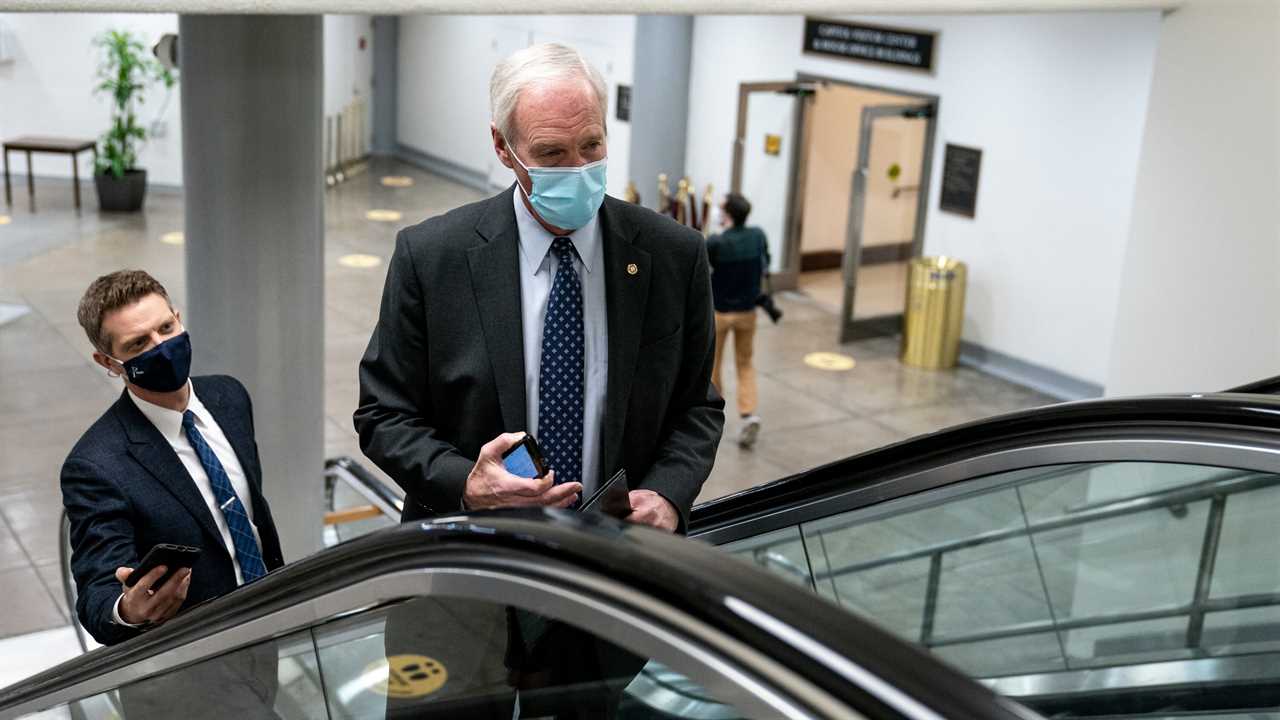

WASHINGTON — With President Biden’s nearly $2 trillion stimulus bill moving toward passage, Senator Ron Johnson brought proceedings to a halt on Thursday by demanding that Senate clerks recite the 628-page plan word by word, delaying action to register his objections.

The maneuver by Mr. Johnson, Republican of Wisconsin, was unlikely to change any minds about the sweeping pandemic aid plan, which would deliver hundreds of billions of dollars for vaccine distribution, schools, jobless aid, direct payments to Americans and small business relief, and has broad bipartisan support among voters. Republicans signaled that they would be unified against it, and Democrats were ready to push it through on their own, using a special fast-track process to blow past the opposition.

But in the Senate, where even the most mundane tasks are subject to arcane rules, any senator can exploit them to cause havoc. The exercise was Republicans’ latest effort to score political points against a measure they were powerless to stop and to punish Democrats with a time-consuming, boredom-inducing chore.

“Is he allowed?” Senator Chuck Schumer of New York, the majority leader, muttered quietly when Mr. Johnson piped up to demand the reading.

He was.

Mr. Johnson did not perform the task himself, though. Instead, it fell to John Merlino, the Senate legislative clerk whose high tenor is known to avid watchers of C-SPAN 2, and a small team of his colleagues who took turns reading to lighten the load.

“It will accomplish little more than a few sore throats for the Senate clerks, who work very hard, day in, day out, to help the Senate function,” Mr. Schumer said in the morning, before the reading began. “And I want to thank our clerks, profoundly, for the work they do every day, including the arduous task ahead of them.”

For hours on Thursday afternoon and into the night, Mr. Merlino and his colleagues took 20- to 30-minute shifts on the Senate dais, bent over a wooden stand, enunciating every “notwithstanding any other provision” and “amounts otherwise made available” of the measure, which was more than 100,000 words long — more than 70 times the length of this article.

A hint of irritation could be heard straining Mr. Merlino’s voice around the dinner hour, as he made his way through Section 4006, on federal funding for disaster-related funeral expenses. There were 117 sections left.

He and his team were the latest Senate officials bearing the brunt of labor for a decidedly partisan process chosen by lawmakers with voting power as Democrats advanced the stimulus plan through a complex process known as budget reconciliation, which allows it to bypass a filibuster and pass with a 51-vote majority.

With Vice President Kamala Harris casting the tiebreaking vote, the Senate voted 51-50 to begin debating the bill on Thursday, just before Mr. Johnson made his objection, pushing off any substantive debate until Friday.

The process, already conducive to sleepless nights, has also thrust the Senate parliamentarian, Elizabeth MacDonough, and her staff under relentless scrutiny for her interpretation of the rules that govern the practice. (The clerks, otherwise occupied, could not be reached for comment.)

Mr. Johnson, who alternated between pacing the chamber and lounging at his desk for the early duration, was sympathetic but unrepentant. His request was allowed because under Senate rules, every senator has to agree to skip the reading of legislative text and move on. Instead, Mr. Johnson objected.

“I feel bad for the clerks who are going to have to read it, but it’s important,” he told reporters, later detailing his plans to prolong debate on the bill, once the reading was over, by forcing votes on a series of amendments. “At a minimum, somebody ought to read it.”

His colleagues, who normally maintain a strict routine of four-day work weeks that end with a 1:45 p.m. vote on Thursdays, said they respected Mr. Johnson’s right to manipulate the rules, even if it did not appear to accomplish anything.

“I’m kind of hard pressed to believe that too many people are going to be glued to their TVs to listen to the Senate clerk read page by page,” said Senator Lisa Murkowski, Republican of Alaska.

Asked when the process would end, Senator Mike Braun, Republican of Indiana, observed, “I think that we’re just a captive of the time here.”

Setting a brisk, modulated pace, Mr. Merlino and a small cluster of colleagues embarked on the reading marathon at 3:21 p.m., paging through the hefty stack of text. (For comparison, the sixth book in the Harry Potter series clocks in at 652 pages.)

Sometimes passing a small lectern back and forth across the dais, they sped through reciting the text to a largely empty chamber, speaking to a diligent carousel of stenographers, floor staff, the Democrat presiding in the chamber and Mr. Johnson, who had to remain on the floor — or find a like-minded Republican to spell him to prevent Democrats from stopping the process and moving on.

By 7:21 p.m., the group had reached page 219.

It was unclear what precedent there was for reading aloud such a substantial piece of legislation, according to the office of the Senate historian, as the Congressional Record does not indicate how much time is spent on the reading of bills.

The Senate has provided funds to employ at least one clerk since 1789, with close to a dozen people now sharing the responsibility of recording the minutes of the Senate, reading legislation, calling the roll and other procedural duties.

“The positions are throwbacks to the days before Xerox machines and the ready availability of hard copies, or now digital copies of legislation,” said Paul Hays, who served as the reading clerk in the House for nearly two decades in the 1990s. “You have to try to achieve a balance between sounding like you’re a robot and sounding like you’re an advocate.”

Having read everything from the impeachment resolution against former President Bill Clinton to a lengthy presidential message from former President Ronald Reagan that took about 35 minutes, Mr. Hays acknowledged that a straight reading was perhaps not conducive to full comprehension.

“It’s arcane legislative language — hearing it read out loud is not like someone’s reading a novel,” Mr. Hays, 75, said in an interview. “It’s just legislative language that oftentimes doesn’t make any sense when it’s read by itself.”

His most recent successor, Joe Novotny, who announced his retirement this week, said he had worked with a coach to develop a routine for resting his vocal cords and doing breathing exercises.

“To be asked to be a voice for the House — it was never lost on me that every day was an honor,” Mr. Novotny, 45, said in an interview on Thursday, his final day of work in the House after more than a decade. “Anytime you are announcing or reading something, it’s not about you. It’s about the voice someone else is using through you.”

Like the staff set to power the Senate floor through Thursday evening, Mr. Novotny was present when the mob stormed the Capitol on Jan. 6, but he returned to work to help narrate the House through a second impeachment debate. He recalled practicing reading the impeachment resolutions and the challenge of reading somber death resolutions and resignations prompted by circumstances that were less than ideal.

“There’s an expectation that we will show up, and we will do our work without falter,” he added. “We’re trained to blend into the woodwork; we don’t want to call attention to ourselves.”

Mr. Novotny praised his Senate counterparts, noting that they frequently had to call the entire alphabetical roll of the Senate — no easy feat, but a practice typically avoided in the House — and deal with a similarly unpredictable schedule.

“I truly have this appreciation for them, because I’ve seen how much they’ve had to sacrifice as well,” he said. “My heart goes out to them. I know it’s a challenging time. But they will absolutely do a perfect job.”

Kitty Bennett contributed research.