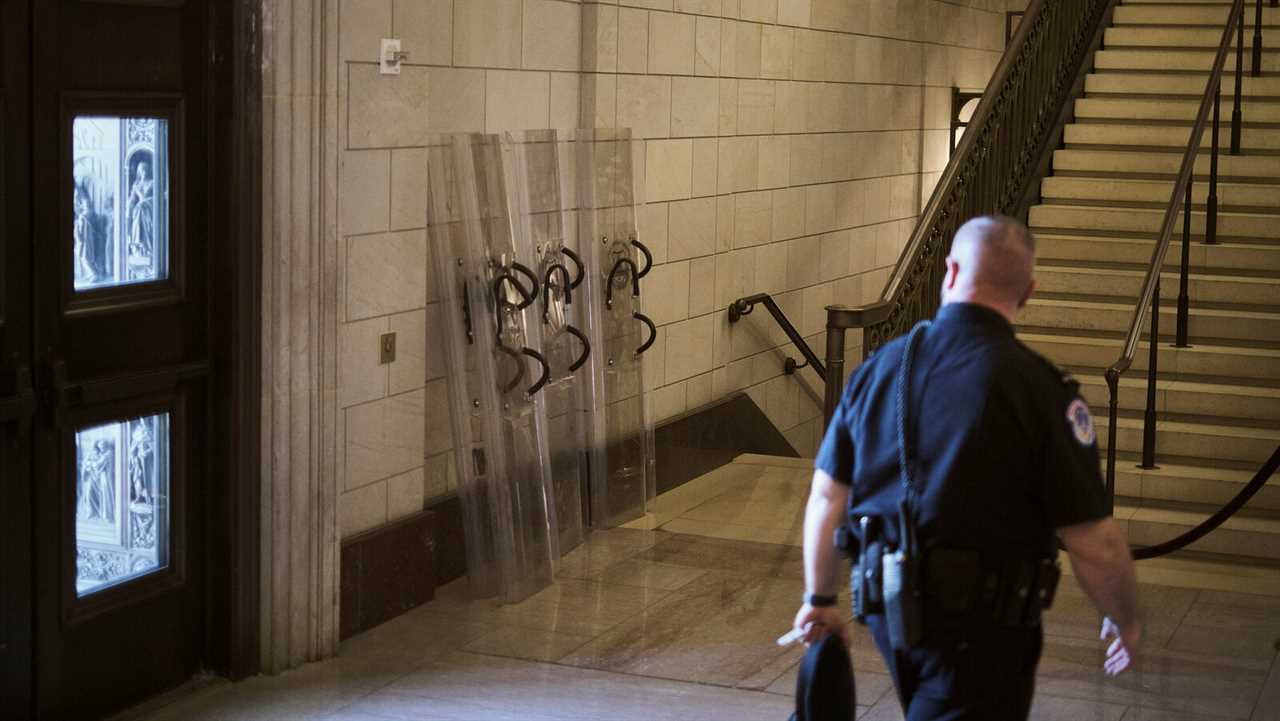

WASHINGTON — Congressional officials have ramped up security and drastically limited the number of attendees for President Biden’s first joint address to Congress on Wednesday, preparing the Capitol for the long-awaited speech under the strictures of a pandemic and a heightened threat level after the deadly Jan. 6 riot.

Inside the cavernous House chamber, Mr. Biden will address only 200 people instead of the usual 1,600 under the special security and public health protocols. Only a fraction of members of the House and the Senate — some chosen by lottery, others on a first-come, first-served basis — have received invitations, and just a small group of the usual dignitaries from the other branches of government will attend.

Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. will be the lone member of the Supreme Court on hand, according to a court spokeswoman. Instead of the full complement of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Gen. Mark A. Milley, the chairman, will attend, along with Defense Secretary Lloyd J. Austin III.

Denied their traditional privilege of inviting a guest to sit in the House gallery for the speech, some lawmakers have resorted to remote invitations. Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s virtual guest is a doctor who runs a community health center for Asian-Americans and Pacific Islanders in her hometown, San Francisco; Representative Sara Jacobs, a California freshman, invited a child-care worker.

But the Capitol itself will be emptier than it has ever been for the speech. The House sergeant-at-arms has asked anyone who does not have a ticket to attend — including lawmakers — to leave the building by 5 p.m. Wednesday, hours before Mr. Biden is to arrive.

The unusual preparations promise to lend a surreal mood to what is usually an elaborate and tradition-bound ritual in Washington — a State of the Union-style address delivered by a newly sworn-in president. They are the latest reminder of the challenges facing Mr. Biden, who took office during one of the more difficult and traumatic stretches in modern American history.

“It’ll be its own wonderful character,” Ms. Pelosi said of the atmosphere for the speech. “We go from 1,600 people to 200 people. That’s a different dynamic, but it has its own worth.”

Already, the speech has been delayed for months after it was initially expected, as the White House and congressional leaders grappled with the public health and security concerns during Mr. Biden’s first weeks in office. Yogananda D. Pittman, the acting chief of the Capitol Police, testified in February that militia groups involved in the Jan. 6 assault wanted to blow up the Capitol and kill lawmakers around Mr. Biden’s first formal address to Congress.

With most cabinet officials staying away, there will be no need for another custom: the annual revelation, usually only minutes before the speech, of a “designated survivor” — one official instructed to stay away from the Capitol in case of a mass casualty attack on the building, to ensure there would be somebody remaining to run the government.

Statuary Hall — usually the loud and unruly gathering place for crowds of journalists who buttonhole lawmakers after the speech for instant reactions — will be empty and silent this year.

Ms. Pelosi said she was confident that the security precautions would keep the Capitol safe, both from extremists who have attacked the building and from the coronavirus, which continues to claim hundreds of lives. She said she had received “a very strong briefing” from William J. Walker, the House sergeant-at-arms, and Chief Pittman about their preparations.

“I wish I had had this briefing before Jan. 6,” Ms. Pelosi said, referring to the attack on the Capitol by a pro-Trump mob that overran the police and injured around 140 officers. “We insisted on knowing every detail of it.”

The Capitol Police said they would close sections of 17 streets to help secure the building before and during the speech.

Senator Chuck Schumer, Democrat of New York and the majority leader, also received a briefing and told his caucus at a lunch meeting of the detailed precautions in place, according to a person familiar with his remarks.

“I feel very safe being there,” Mr. Schumer said. “I told my colleagues that, and they did a very good job. There’s lots of different levels of security.”

The Capitol continues to operate under a heightened state of security. Visitors have been restricted since last spring because of the virus and, after Jan. 6, security officials called in the National Guard and erected fences outside the building.

Officials had just begun to take down some of those fences when a man crashed his car into two police officers at the complex this month, killing an officer standing guard.

“On the Capitol complex, the level of existential threats to the U.S. Capitol and grounds are increasing as well,” Chief Pittman told a Senate committee last week.

The Capitol Police have recorded a nearly 65 percent increase in threats to lawmakers during the first four months of 2021 compared with the same period in 2020, Chief Pittman testified. She said total threats had doubled since 2017, with an “overwhelming majority of suspects residing outside” the capital region.

The agency has requested a budget increase of more than $100 million to address security issues, while the Senate sergeant-at-arms is requesting a more than $50 million budget increase.

Senators said on Tuesday that they felt confident that the building would be secure, though not all of them could get a seat at the invite-only event.

“I did not get a golden ticket,” said Senator Kirsten Gillibrand, Democrat of New York, explaining that her name had not come up in a lottery system that Senate Democrats were using. “I’m grateful for brave Capitol Police as well as our National Guard that are here. They are going above and beyond to make sure that we are protected.”

(Ms. Gillibrand’s staff later said she had been able to secure an invitation from a wait list.)

Senator Chris Van Hollen, Democrat of Maryland, said he supported the instructions from the Capitol’s top doctor to follow guidelines issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention even though the joint address would have a “very different sort of atmosphere” from past speeches.

“We’re in a unique moment in a unique time,” Mr. Van Hollen said. “But the speech will be seen by the country in much the same way. Maybe there’ll be a little less jumping up and down every three seconds for applause.”

Many Republicans said they did not plan to attend, given the restrictions and the distancing requirements that mean some lawmakers will sit in the House gallery, rather than on the floor of the chamber.

“They’re going to make you sit in the balcony and all that,” said Senator Marco Rubio, Republican of Florida. “At that point, you’re probably better off just watching on television.”

Mr. Rubio said he did not fully understand the virus-related restrictions in place, “because we sat next to each other for six days, for hours on end, doing an impeachment trial.”

Senator Ron Johnson, Republican of Wisconsin and an ardent supporter of former President Donald J. Trump, said he did not plan to attend, even though had received a slot. He said he would give it to someone “who wants to go more than I do.”

But Senator Lindsey Graham, Republican of South Carolina, said he would be there in person, in part out of respect for the presidency and in part because “I got nothing else to do.”

“I want to hear the president,” Mr. Graham said. “I think we should go, out of respect for the office and him.”

Helene Cooper and Nicholas Fandos contributed reporting.