For decades, Senator Lindsey Graham traveled the world with his friend John McCain, visiting war zones and meeting with foreign allies and adversaries, before returning home to promote the Republican gospel of an internationalist, hawkish foreign policy.

But this week, after President Biden announced that troops would leave Afghanistan no later than Sept. 11, Mr. Graham took the podium in the Senate press gallery and hinted that spreading the party’s message had become a bit lonely.

“I miss John McCain a lot but probably no more than today,” Mr. Graham said. “If John were with us, I’d be speaking second.”

Mr. McCain, the onetime prisoner of war in Vietnam, in many ways embodied a distinctive Republican worldview: a commitment to internationalism — and confrontation when necessary — that stemmed from the Cold War and endured through the presidencies of Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush before evolving after the Sept. 11 attacks to account for the threat of global terrorism.

Then came Donald J. Trump, who campaigned on a promise to put America first, an isolationist mantra that resonated with a nation weary of endless wars. Now, out of power in Washington, Republicans have splintered into disparate factions, with few figures to take the lead.

In the Senate, lawmakers who built reputations as leaders on foreign policy — like Mr. McCain and Senators Richard Lugar and John Warner — are long gone. Mr. Trump defenestrated much of the party’s policymaking establishment by alienating dozens of foreign policy experts, who refused to support his campaign, let alone enter his administration.

And for ambitious Republican officials, the political calculation remains stark: To the extent that Republican voters care at all about foreign policy issues, many have come to embrace Mr. Trump’s nationalistic views on issues like trade, overseas military ventures and even Russia.

“Boy, I’m hard-pressed,” said Chuck Hagel, the former Republican senator, when asked to name a G.O.P. foreign policy expert in the Senate. “The emphasis on foreign policy probably hasn’t been the same with senators. But I can’t think of a Dick Lugar or a John Warner or any of the guys I served with.”

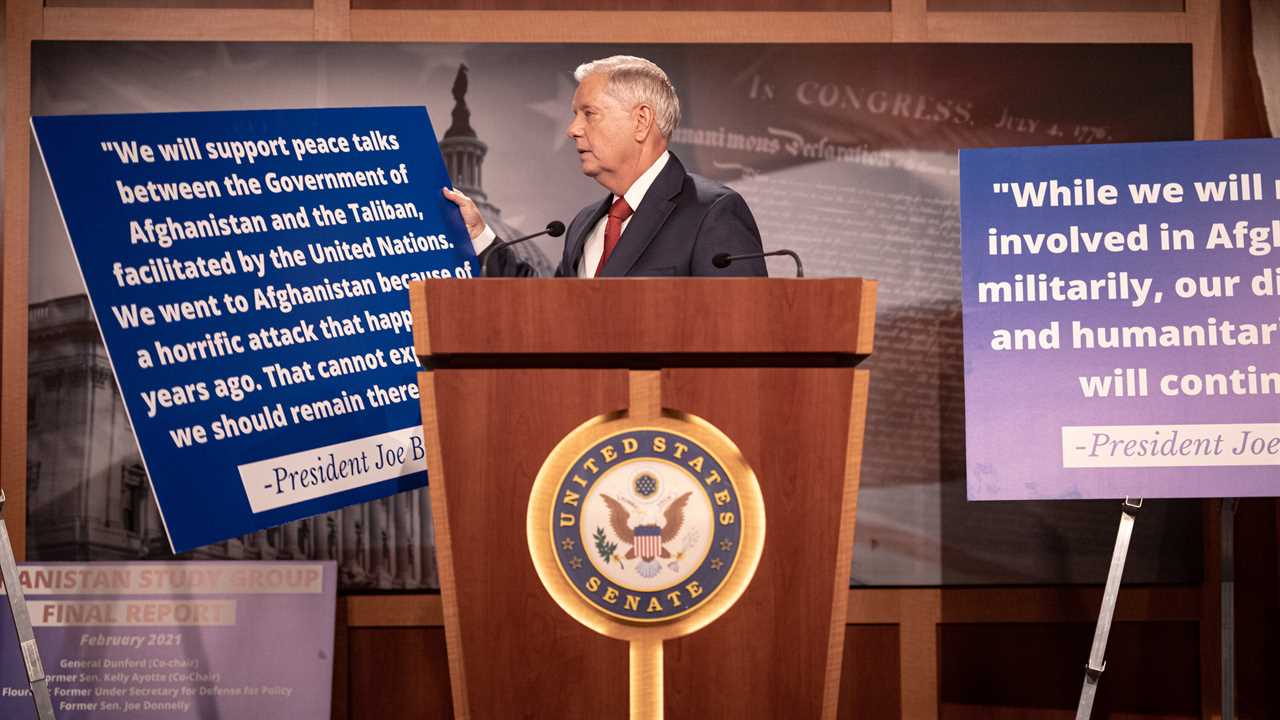

Mr. Graham, who made an unsuccessful run for president and was always overshadowed by Mr. McCain as a Republican voice on foreign policy, spoke for more than half an hour at a news conference on Wednesday, walking listeners through a history of the Afghan conflict.

“This is what they’re capable of doing when we ignore the threat of the enemy,” he said, gesturing to a large photo of a burning World Trade Tower. “The likelihood of this and this happening again is going through the roof after President Biden’s decision today.”

Other leading Republicans, some of whom condemned Mr. Trump’s pledge to withdraw all troops from Afghanistan by May 1, also pressed the traditional Republican viewpoint of using American might to protect the nation’s interests.

Mitch McConnell, the Senate minority leader, warned that pulling out the troops would be a “grave mistake.”

“Apparently, we’re to help our adversaries ring in the anniversary of the 9/11 attacks by gift-wrapping the country and handing it right back to them,” he said in a speech on the Senate floor.

But that view was far from uniform. Senator Rand Paul, long a vocal opponent of foreign intervention, said he was “grateful” to Mr. Biden. “Enough endless wars,” he tweeted. Senator Ted Cruz told CNN that he was “glad the troops are coming home.”

And Senator Josh Hawley of Missouri, who has ambitions of developing a new policy framework for the party, praised the decision.

“President Biden should withdraw troops in Afghanistan by May 1, as the Trump administration planned, but better late than never,” he said. “It’s time for this forever war to end.”

The dispute is hardly new, or contained to the G.O.P. Many Democrats have come to believe that foreign policy should serve domestic economic and political goals far more heavily than in the past. But Senator Jack Reed, the Democratic chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, has warned that a full withdrawal from Afghanistan could pose a significant national security threat.

For Republicans, the shift inward comes as their long dominance over issues of national security and international affairs is waning. Mr. Trump rejected Republican foreign policy orthodoxy but largely struggled to articulate a cohesive countervailing view beyond a vague notion of putting America first. He embraced strongmen, cast longtime allies as free riders and favored a transactional approach, rejecting any notion of the kind of values-driven foreign policy that had defined the party for decades.

The party’s foreign policy establishment found itself exiled from Mr. Trump’s government and fighting for relevance against an insurgent isolationist party base.

“To say that there is a single Republican foreign policy position is to miss what’s been happening within the conservative movement on these issue for the last 20 years,” said Lanhee Chen, a Hoover Institution scholar and policy adviser to a number of prominent Republican officials. “The characters change, the terminology changes, but the differences remain.”

Yet, that old debate carries new political resonance for the party, as it confronts the political need to develop a platform that goes beyond simply opposing whatever the Democratic administration puts in place.

“Anytime you don’t have the White House and you don’t have control of the Congress, it is a time to look inward and figure out what the predominate view is,” Mr. Chen said.

With the Republican base more focused on issues like relitigating the election and so-called cancel culture, there has been little discussion about what larger agenda the party should pursue. But some experts see an opportunity for Republicans to articulate a new conservative perspective on national security issues.

Foreign policy, particularly withdrawing from Afghanistan, was one of the few areas where Republican elected officials were willing to publicly criticize Mr. Trump. Now that he has left office, foreign policy experts who condemned Mr. Trump throughout his administration, and endorsed Mr. Biden by the dozens, are hopeful that party consensus will revert to the traditional Republican values of free trade, more open immigration and a re-embrace of international alliances.

“Restoration does feel like the right word, both in the long-shot nature of it occurring, and in the correction to what have long been identified as conservative policies,” said Kori Schake, who directs foreign and military policy studies at the conservative American Enterprise Institute and served on the National Security Council under President George W. Bush.

Yet chances that Republicans will achieve a complete restoration of the traditional party platform seem low, particularly if Mr. Trump continues to flex his political power among his base. The former president captured the hearts and minds of his followers, shifting opinions on issues of globalism. During his administration, polling showed Republican voters adopted a more positive view of Russia and became more skeptical of trade agreements and international alliances.

A survey conducted by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs last year found that Republican voters preferred a more nationalist approach, valuing economic self-sufficiency, and taking a unilateral approach to diplomacy and global engagement

When asked about the effects of the coronavirus pandemic, 58 percent of Republicans surveyed said the outbreak showed the United States should be less reliant on other countries, compared with just 18 percent of Democrats who said the same. Close to half of Republicans agreed that “the United States is rich and powerful enough to go it alone, without getting involved in the problems of the rest of the world,” and two-thirds said they preferred that the country produce its own goods, as opposed to buying or selling overseas.

Another survey by Tony Fabrizio, one of Mr. Trump’s pollsters, found that only 7 percent of Republicans prioritize national security and foreign policy issues, compared with nearly a quarter who care about economic issues.

“We don’t want to engage in nation building, we don’t want to engage in endless police actions,” said John McLaughlin, who also conducted polling for Mr. Trump. “President Trump was ahead of the curve when he was saying we need to have an American first policy, and that’s where public opinion is within the party.”

Much of that debate may play out in the early phases of the 2024 presidential race, as Republican contenders attempt to burnish their foreign policy credentials. Already, some are casting themselves as heirs to the Trump legacy, with Mike Pompeo, the former secretary of state, and Nikki Haley, the former ambassador to the United Nations, widely assumed to be weighing presidential bids.

Mr. Pompeo, who recently became the co-chairman of a new foreign policy group at the Nixon Foundation that aims to reassert “conservative realism,” said he supported Mr. Biden’s decision.

“Reducing our footprint in Afghanistan is completely appropriate,” Mr. Pompeo said in an interview on Fox News. “It’s the right thing.”

The comment marked rare praise from a man who is emerging as the most outspoken critic of Mr. Biden among former top Trump officials.

Of course, as the Fox News hosts pointed out, had Mr. Trump won re-election, the troops would have been coming home next month — with the full support of Mr. Pompeo, if not many other Republican leaders.