Ebony Carter faced an uphill climb when she decided to run for the Georgia State Senate last year. Her deeply Republican district south of Atlanta had not elected a Democrat since 2001, and a Democrat hadn’t even bothered campaigning for the seat since 2014.

State party officials told her that they no longer tried to compete for the seat because they didn’t think a Democrat could win it. That proved correct. Despite winning 40 percent of the vote, the most for a liberal in years, Ms. Carter lost.

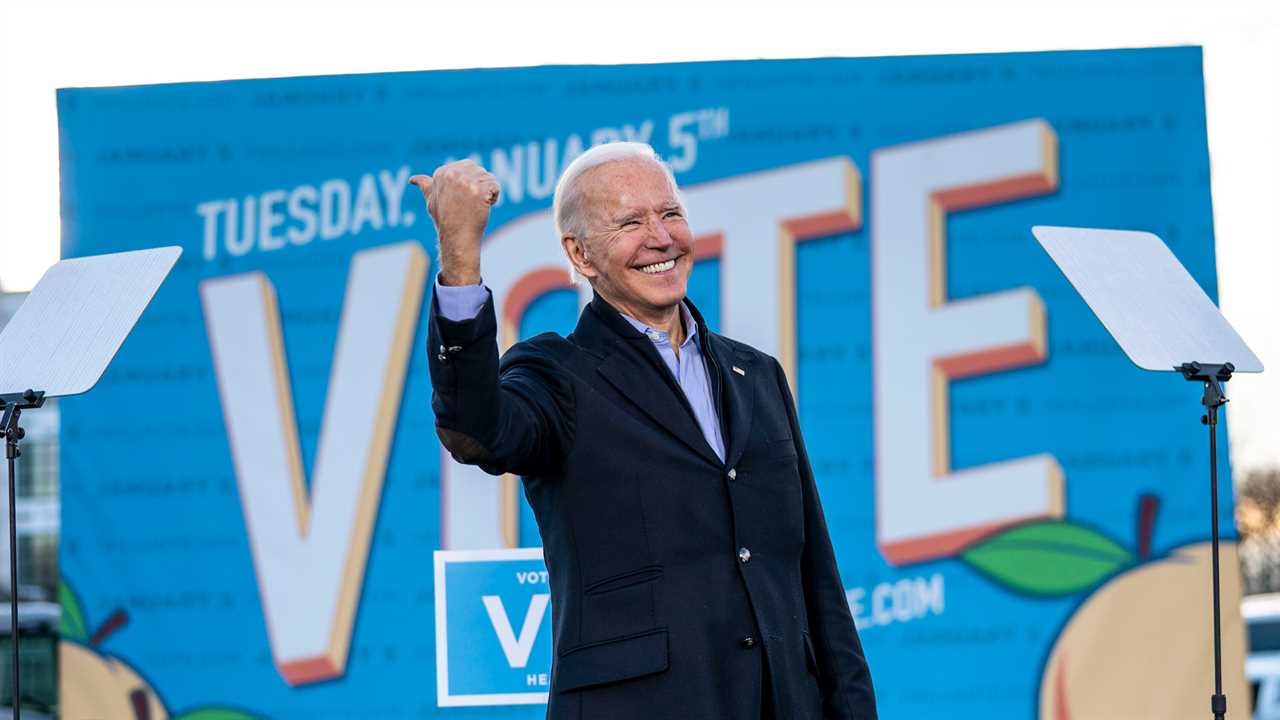

But her run may have helped another candidate: Joseph R. Biden Jr.

The president, who eked out a 12,000-vote victory in Georgia, received a small but potentially important boost from the state’s conservative areas if at least one local Democrat was running in a down-ballot race, according to a new study by Run for Something, an organization dedicated to recruiting and supporting liberal candidates. That finding extended even to the state’s reddest districts.

The phenomenon appeared to hold nationally. Mr. Biden performed 0.3 percent to 1.5 percent better last year in conservative state legislative districts where Democrats put forward challengers than in districts where Republicans ran unopposed, the study found. The analysis was carried out using available precinct-level data in eight states — Florida, Ohio, North Carolina, Arizona, Georgia, Texas, Kansas and New York — and controlling for factors like education to create a comparison between contested and uncontested districts.

The study showed a reverse coattails effect: It was lower-level candidates running in nearly hopeless situations — red districts that Democrats had traditionally considered no-win, low-to-no-investment territory — who helped the national or statewide figures atop the ballot, instead of down-ballot candidates benefiting from a popular national candidate of the same party.

“The whole theory behind it is that these candidates are supercharged organizers,” said Ross Morales Rocketto, a co-founder of Run for Something. “They are folks in their community having one-on-one conversations with voters in ways that statewide campaigns can’t do.”

The idea isn’t new, but it is the first time that a comprehensive study has been done on the possibility of such a reverse coattails effect, and it comes as the Democratic Party ramps up its strategizing for the midterm elections next year.

In 2005, when Howard Dean became the chairman of the Democratic National Committee, he tried to institute a “50-state strategy” to build up party infrastructure and candidate recruitment at every level and in every state — even in solidly Republican districts. The hope was that if there was at least one Democrat running in every county, it would help the party build a larger base for future elections. Mr. Dean was met with skepticism from national strategists who believed in a more conventional method of focusing limited campaign resources on swing districts. After his tenure, the strategy fell out of favor.

What tends to derail any such 50-state, all-districts strategy are the limited resources that both parties have in any election, and the realpolitik considerations that inevitably lead them to pour disproportionate amounts of money into certain races seen as particularly important and winnable.

“If you have candidates dedicated to ground game, then it could be helpful, but usually campaigns at the lower end of the spectrum don’t have that kind of money, and it’s certainly not done by parties as much anymore,” said Ed Goeas, a Republican pollster. He said that one reason for this could be that controlling messaging down the ballot is hard to do when campaigns at the top of the ticket have different approaches to issues from those of local candidates.

For the last few cycles, Democrats’ major priorities have been retaking the House, the Senate and the presidency. Now, with the party in control of all three, down-ballot organizers want the party to shift some of its focus to state legislative races.

Mr. Morales Rocketto expressed hope that the study would start a conversation among Democrats on how they invest in state and local races.

During the 2020 election cycle, Democratic campaigns for the Senate, like Amy McGrath’s in Kentucky and Jaime Harrison’s in South Carolina, raised huge sums of money, in some cases topping $90 million for a single campaign. By comparison, the Democratic Legislative Campaign Committee said it raised $51 million for legislative races in 86 chambers across 44 states.

“Now that we’ve gotten through the 2020 election, we really need to make sure that this is what we’re focused on,” Mr. Morales Rocketto said. “We’ve elected Joe Biden, but Trump and Trumpism and the things he’s said and stood for are not gone, and we could lose everything again.”

And what those losses look like is already known, Jessica Post, the president of the Democratic Legislative Campaign Committee, argued.

“When Republicans took control of 21 state legislative chambers in 2010, we lost control for a near decade to win the United States Congress,” she said. “We now have a challenge with keeping the United States Senate, and Republicans are eroding our voting rights in these state legislatures.”

Since the presidential election, Republican-run legislatures across the country have been drafting bills to restrict voting access, prompting Democratic calls for additional local party infrastructure. The way to get that investment and attention from the Democratic National Committee, Mr. Morales Rocketto said, is to highlight how a bottom-up approach can help the party at the national level, too.

Ms. Post echoed that sentiment. “So much of the building blocks of American democracy are truly built in the state,” she said.

Republicans have lapped Democrats in their legislative infrastructure for years, said Jim Hobart, a Republican pollster. “Democrats are pretty open at a legislative level that they’re playing catch-up,” he said. “For whatever reason, Democrats have gotten more fired up about federal races.”

Mr. Hobart said that both parties should want to have strong candidates running for office up and down the ballot, because parties never know what districts will become competitive. For Republicans in 2020, some of those surprise districts were along the southern border of Texas, which had previously been a relatively blue region.

“It came as a shock to everybody that Republicans ran as strong in those districts as they did,” Mr. Hobart said. “But if you have candidates on the ballot for everything, it means you’re primed to take advantage of that infrastructure on a good year.”

The new study will be just one consideration as the D.N.C. reviews its strategy for state legislative and other down-ballot races in the midterms. The committee is pledging to increase investment in such races, both to help win traditional battleground states and to grow more competitive in red-tinted states that are trending blue.

Officials at the D.N.C., who declined to speak on the record about the study, pointed to Kansas, which has a Democratic governor but voted for former President Donald J. Trump by 15 percentage points, as an example of a state where they’d like to put the study’s findings into action.

Democrats in the state are gearing up to try to re-elect Gov. Laura Kelly, and Ben Meers, the executive director of the Kansas Democratic Party, said he hoped to test the theory. He said that having Democrats campaign in deep-red districts required a different type of field organizing.

“There are some counties where if the state party can’t find a Democrat, we can’t have an organized county party, because the area is so red,” he said. “But if we can run even the lone Democrat we can find out there, and get a few of those votes to come out — you know the analogy: A rising tide lifts all Democratic ships.”

Some Democratic strategists in Kansas noticed that phone-bank canvassers had more success with voters during the general election when they focused on congressional and local candidates, rather than headlining their calls with Mr. Biden. They’re hoping that building local connections in the state will help Ms. Kelly’s campaign.

In Georgia, Run for Something believes that Ms. Carter’s presence on the ballot significantly helped Mr. Biden’s performance in her area of the state. While the group said that district-level data alone could be misleading, and needed to be combined with other factors taken into account in its analysis, Mr. Biden averaged 47 percent of the vote in the three counties — Newton, Butts and Henry — in which Ms. Carter’s district, the 110th, sits. That was five percentage points better than Hillary Clinton’s performance in 2016.

Ms. Carter said she had tried to start grass-roots momentum in the district. “For me, running for office was never an ambition,” she said. “It was more so out of the necessity for where I live.”

Ms. Carter’s district has grown exponentially during the last decade, bringing with it changing demographics and different approaches to politics. She knew through previous political organizing and her own campaigning that many people in her district, including friends and family, didn’t know when local elections were, why they were important or what liberal or conservative stances could look like at a local level.

Ms. Carter said she spent a lot of time during her campaign trying to educate people on the importance of voting, especially in local races that often have more bearing on day-to-day life, like school and police funding.

“I thought it was a lot of the work that people didn’t want to do or felt like it wasn’t going to benefit them,” she said. “We are not going to win every race, but we could win if we just did the legwork.”

Nick Corasaniti contributed reporting.