The suburbs of Cobb County, Ga., boomed during white flight on the promise of isolation from Atlanta. Residents there dating to the 1960s did not want Atlanta problems, or Atlanta transit, or Atlanta people. As a local commissioner once infamously put it, he would stock piranha in the Chattahoochee River that separates Cobb from Atlanta if it were necessary to keep the city out.

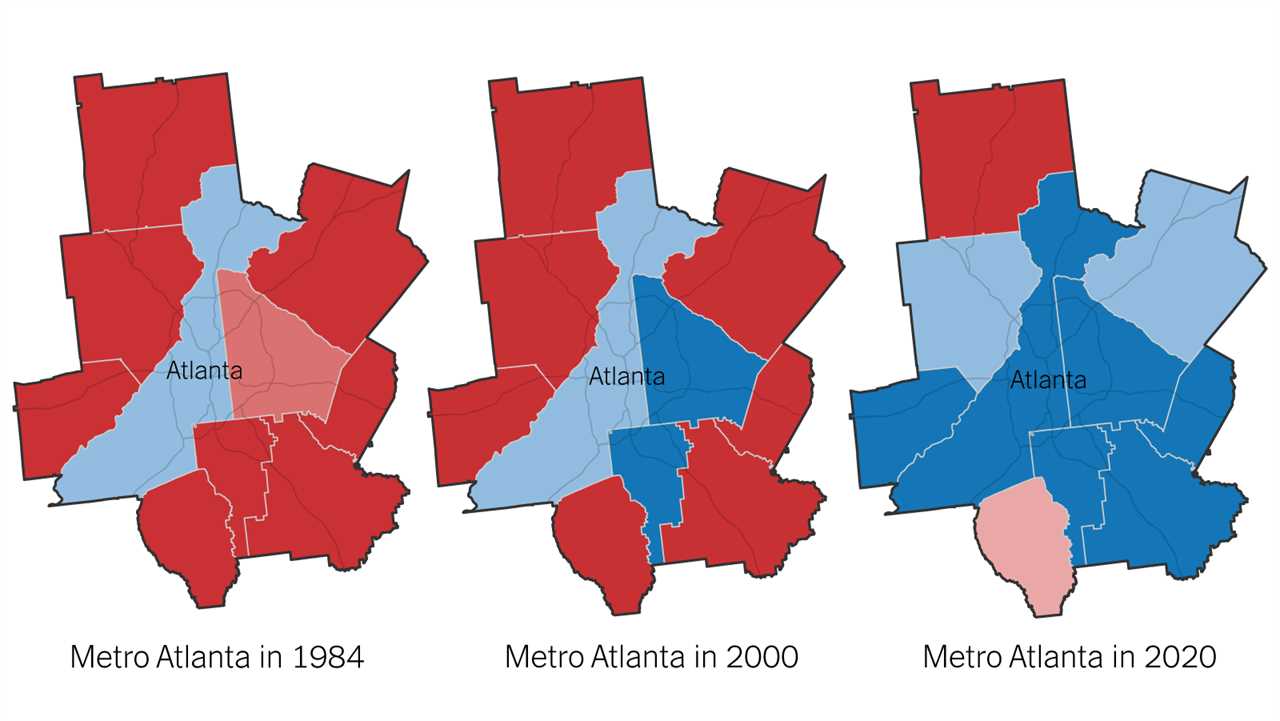

The county became a model of the conservative, suburban South, opposed to the kind of federal meddling that integrates schools, or the kind of taxes that fund big infrastructure. And then, this year, after timidly embracing Hillary Clinton in 2016 (she won the area by just two points), Cobb County voted for Joe Biden by 14 percentage points. And Democrats swept the major countywide races.

“It’s been this evolution of Cobb from a white-flight suburb to, now, I went to a Ramadan meal in a gated community in Cobb County that was multiracial,” said Andrea Young, the executive director of the Georgia A.C.L.U., and the daughter of the former Atlanta mayor Andrew Young. “This is the story,” she said, “of Atlanta spilling out into the metro area.”

Around the region, suburban communities that once defined themselves in opposition to Atlanta have increasingly come to resemble it: in demographics, in urban conveniences and challenges, and, finally, in politics. Rather than symbolizing a bulwark against Black political power, these places have become part of a coalition led by Black voters that is large enough to tip statewide races — and that could hand control of the Senate to Democrats next month.

“In Atlanta, they thought they could draw a line, and they thought it would be permanent, whether it was the Chattahoochee River, or Sandy Springs forming its own city to keep Atlanta out,” said Kevin Kruse, a Princeton historian whose book “White Flight” followed the mass migration from Atlanta in the civil rights era. “That was just a holding operation. It couldn’t stop those forces of progress.”

Mr. Kruse says these suburbs gave rise to a “politics of suburban secession.” Their voters prized private spaces over the public good, low taxes over big government, local autonomy over federal intervention. Newt Gingrich, a House member from Cobb County who embodied that agenda, became House Speaker in 1995. And neighboring counties were as reliably red. In 2004, George W. Bush carried Cobb by 25 points. He carried Gwinnett County to the east by 32 points, and Henry County south of Atlanta by 34 points.

Such suburban politics became national in scope. But in Atlanta, they emerged in reaction to a very particular political history.

In Atlanta, dating to the 1940s under Mayor William B. Hartsfield, who was white, African-American voters and the white business class have long had a political alliance, one born out of shared opposition to working-class white segregationists who were viewed as bad for both racial progress and for business.

“Atlanta’s ethic was ‘If you can show me how to make money, I can work with you on the prejudice part,’” Ms. Young said. “‘I’m willing to give up some of my white supremacy, if I can make some more money.’”

That fragile alliance helped integrate neighborhoods, parks and schools, often in tentative and token ways but without the violent mass resistance of other Southern cities. It also helped Atlanta establish what would become the busiest airport in the country, cementing the city’s reputation as a home of corporate headquarters and, eventually, the 1996 Olympics (the volleyball competition, originally planned for Cobb County, was moved after officials there passed a resolution condemning gay lifestyles).

What held the biracial coalition together — in “The Atlanta Way” — wasn’t exactly a shared moral mission.

“In fact, the corporate elite were very specific that they were pursuing enlightened self-interest — that’s the term they themselves used,” said Clarence Stone, whose 1989 book studying the coalition, “Regime Politics,” is essential reading in the city even today. “It wasn’t that this was the moral path. This was the pragmatic path.”

White segregationists unwilling to share neighborhoods, schools and power with African-Americans left the city. Over time, many middle-class whites did, too, as the integration they supported in theory touched their own schools and blocks. The alliance also shifted, as African-Americans like Mr. Young won offices once held by white leaders in what became a smaller, more predominantly Black city.

But the success of the Atlanta economy ultimately helped seed the ground for Georgia’s political change. The region attracted new residents from all over — not just white families looking for low taxes, but also tech entrepreneurs from the West Coast, immigrants from Asia, and Black professionals from Northern cities.

According to the real estate company Redfin, Los Angeles, Washington and the Bay Area are now among the most common metros where people appear to be searching for a move to the Atlanta area.

In the region’s four core counties of Fulton, DeKalb, Cobb and Gwinnett, the African-American population grew by 17 percent between 2010 and 2018. It’s not so much that African-Americans moved across the Chattahoochee; they moved from Memphis and Chicago.

“Even when I was campaigning, there are those people who think ‘you shouldn’t be representing us because you didn’t grow up here,’” said Erick Allen, who won his second term as a Democratic state representative from Cobb County last month after flipping a Republican seat. “And I have to remind them, well that makes me the majority. Most of us that are here, we’re here by choice, not by lineage.”

Mr. Allen, who is African-American, grew up in Nashville. His wife, born in Jamaica, was raised in New York. They chose to live in Cobb County because of what it’s becoming, not because of what it was 30 years ago, he said.

“This isn’t Newt Gingrich’s Cobb County,” Mr. Allen said. “This truly is Lisa Cupid’s Cobb County.”

Ms. Cupid, a Democrat, became the first African-American woman to be elected the county commission chair this year.

Suburbs around the region have also become home to lower-income residents priced out by Atlanta’s rising housing costs. Suburban foreclosures during the housing crisis also opened up neighborhoods that were once owner-occupied to more renters.

Add to these changes the efforts of some suburban communities to attract young professionals — by building denser, walkable town centers.

“There’s a replication of urban life,” said A.J. Robinson, the president of Central Atlanta Progress, the business alliance that has been central to Atlanta’s coalition since the 1940s. “With that you begin to recognize, hey, we have urban issues that are very much like the city of Atlanta. You have more density, you have more people who are concerned about civic affairs, you have more issues of infrastructure.”

Denser and more diverse places create their own politics, he said, apart from the politics that new residents bring.

“You have to think about how if we want more stuff, we have to tax ourselves,” Mr. Robinson said. “That’s not a Republican concept.”

These trends have created a diverse region with both a growing Black population and new white residents whose politics differ from those of past white voters.

“You now have the basis for a multiracial electoral coalition,” said Andra Gillespie, a political scientist at Emory. “Whether or not they’re all voting for the same reasons — that’s a totally different topic that’s up for discussion.”

For the first time in Georgia, African-Americans made up the majority of a winning presidential candidate’s coalition, according to Bernard Fraga, another Emory political scientist. That is a remarkable evolution of the old biracial alliance that many white Georgians rejected.

“This really does feel like the old Hartsfield coalition — it’s just happened beyond the city limits,” said Professor Kruse, the historian. That alliance includes white college-educated suburbanites who, like the downtown business leaders before them, he said, “aren’t necessarily personally liberal but who see the forces of illiberalism as being hostile to their own interests.”

Now it is nationalist dog whistles and political conspiracy theories that are bad for business.

This larger Democratic coalition may also prove fragile, in some of the same ways. The Atlanta Way, for one, has often left out the interests of lower-income African-Americans.

“I don’t think it’s a strong enough coalition to create more equity in terms of improving majority-minority schools, or building more affordable housing,” said Deirdre Oakley, a sociologist at Georgia State. And some of these suburbs, with their rising diversity, still don’t want Atlanta transit.

But the coalition will have a chance to demonstrate its might again soon, in the Senate runoffs, and in a governor’s race likely to include Stacey Abrams again in 2022.

“One way you could characterize what happened a month ago is this was the first time — maybe the first time ever — where urban Georgia outvoted rural Georgia,” said Charles S. Bullock III, a political scientist at the University of Georgia.

That urban tally includes Savannah, Macon and Athens, but now, also, voters in suburban communities that, a generation ago, defined themselves as anything but urban.

Quoctrung Bui contributed to this article.