Democrats on Tuesday unveiled a long-awaited linchpin of their drive to protect voting rights, introducing legislation that would make it easier for the federal government to block state election rules found to be discriminatory to nonwhite voters.

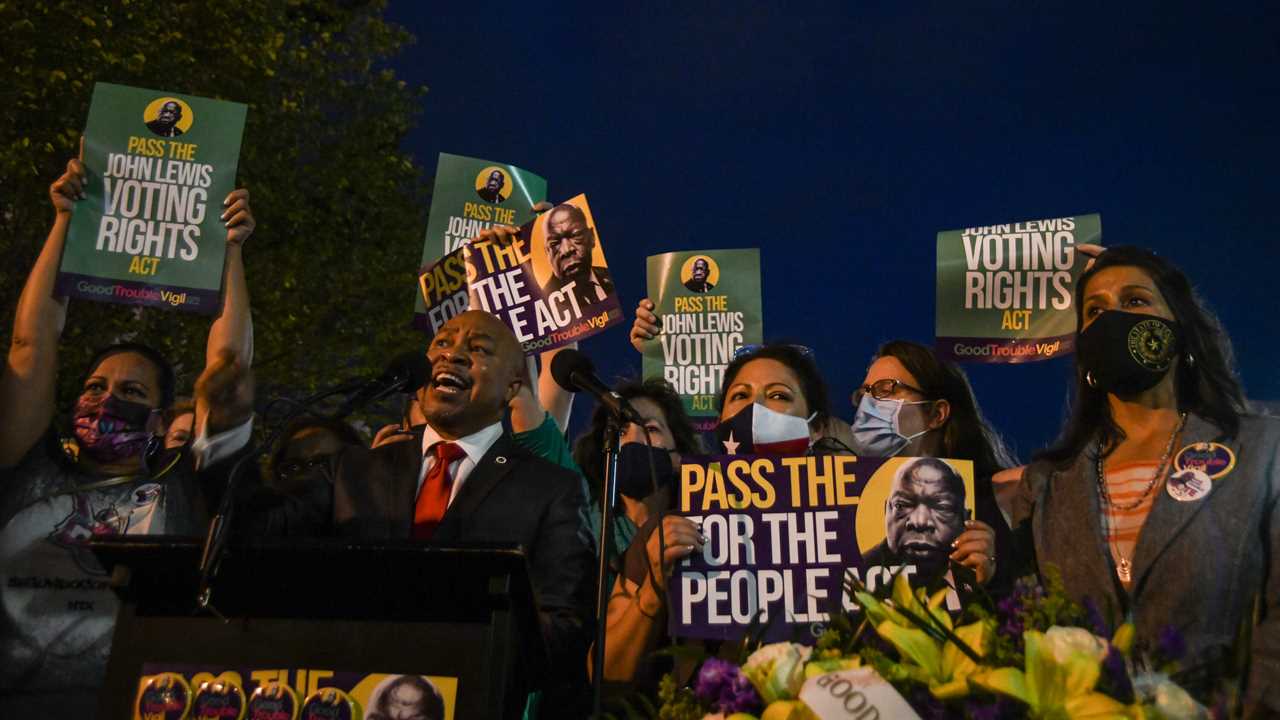

House leaders expect to pass the bill, named the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act after the late civil rights icon, during a rare August session next week. They say it would restore the full force of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 after a pair of adverse Supreme Court rulings and that it would help combat a wave of restrictive new election laws in Republican-led states.

“Today, old battles have become new again as we face the most pernicious assault on the right to vote in generations,” said Representative Terri Sewell, the bill’s chief author and a Democrat from Alabama’s civil rights belt, where Mr. Lewis and others staged a national campaign for voting rights in the 1960s. “It’s clear: federal oversight is urgently needed.”

But like other voting rights legislation to come before Congress this year, its chances of passing the evenly divided Senate are exceedingly narrow. Only one Republican, Senator Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, is likely to support the legislation, leaving Democrats far short of the 60 votes they would need to break a Republican filibuster and send the bill to President Biden’s desk.

Senate Republicans already blocked Democrats’ other marquee voting rights bill, the For the People Act, which would establish national mandates for early and mail-in voting and end gerrymandering of congressional districts. And while Democratic leaders in the Senate have vowed more votes on the matter in September, unless all 50 Democrats unite in a long-shot bid to change Senate filibuster rules, they are headed for an identical outcome.

The legislation introduced by Ms. Sewell on Tuesday is an effort to restore key pieces of the landmark 1965 voting bill struck down or weakened by the Supreme Court over the last decade. Doing so, its proponents say, would make it far harder for states to restrict voting access in the future.

The most consequential ruling dates to 2013, when the justices effectively invalidated a section of the law that required states and localities with a history of discriminatory voting rules to clear any changes to their elections policies with the federal government. At the time, the justices said that the formula used to determine which states were subject to clearance was out of date and invited Congress to update it.

The bill also attempts to respond to a decision just last month in Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee that effectively made it more difficult to challenge state voting laws as discriminatory in court using a different provision of the law.

Voting rights activists fear the two decisions will make it far easier for those in power to marginalize voters of color at the ballot box and during the once-in-a-decade redistricting process underway this year. Just this year, more than a dozen Republican-led states have enacted restrictive new voting laws.

“We have seen an upsurge in changes to voting laws that make it more difficult for minority citizens to vote and that is even before we confront a round of decennial redistricting where jurisdictions may draw new maps that have the purpose or effect of diluting or retrogressing minority voting strength,” Kristen Clarke, the assistant attorney general for civil rights, told a House panel on Monday.

Republicans joined Democrats in large numbers to reauthorize the full Voting Rights Act as recently as 2006. But since the high court’s 2013 decision, they have shown little interest in updating the statute, arguing that discrimination is largely a thing of the past and that the federal government ought to stay out of states’ rights to set their own election rules.

Asked about the bill on Tuesday, Russell Dye, a spokesman for Representative Jim Jordan of Ohio, the top Republican on the House Judiciary Committee, accused Democrats of ignoring “real problems” like the crisis of Afghanistan, the influx of migrants at the southern border and rising crime “in favor of pushing a radical far-left political agenda.”