Democrats in Congress are quietly splintering over how to handle the expansive voting rights bill that they have made a centerpiece of their ambitious legislative agenda, potentially jeopardizing their chances of countering a Republican drive to restrict ballot access in states across the country.

President Biden and leading Democrats have pledged to make the elections overhaul a top priority, even contemplating a bid to upend bedrock Senate rules if necessary to push it through over Republican objections. But they are contending with an undercurrent of reservations in their ranks over how aggressively to try to revamp the nation’s elections and whether, in their zeal to beat back new Republican ballot restrictions moving through the states, their proposed solution might backfire, sowing voting confusion and new political challenges.

The hand-wringing demonstrates how urgent the voting issue has become for both parties since November, when President Donald J. Trump spread false claims of voter fraud that many Republicans believed. In the months since, Republican-led statehouses have advanced a wave of new laws clamping down on ballot access.

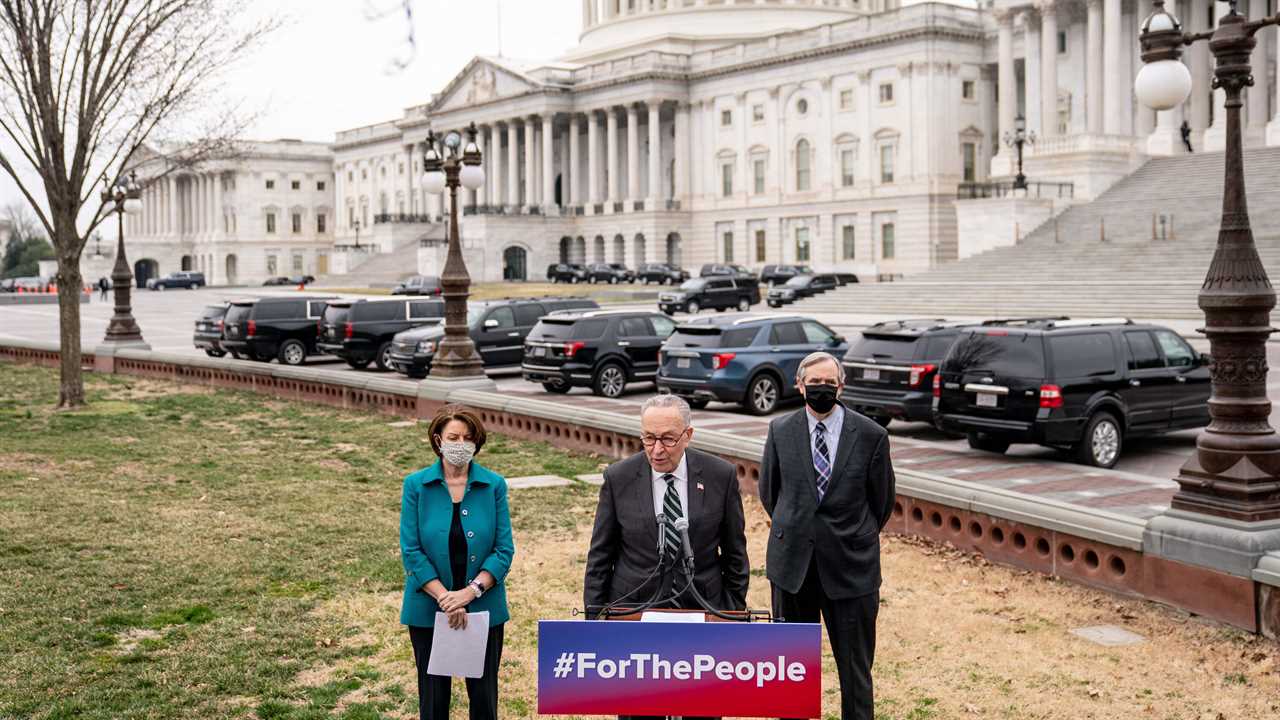

Democrats have coalesced around the idea that pushing back on such measures is a modern-day civil rights battle that the party cannot afford to lose. “Failure,” Senator Chuck Schumer of New York, the majority leader, said last week, “is not an option.”

But while few Democrats are willing to publicly say so, the details of the more than 800-page bill — which would radically reshape the way elections are run and make far-reaching changes to campaign finance laws and redistricting — have become a point of simmering contention. Some proponents argue that Democrats should break off a narrower bill dealing strictly with protecting voting rights to prevent the legislation, known as the For the People Act, from collapsing amid divisions over other issues.

“Democrats have a narrow opportunity. There is a window here that could close anytime,” said Richard L. Hasen, an election law expert at the University of California, Irvine. “I worry the kind of fights necessary to keep even the Democratic coalition together could blow up the whole thing and lose the chance to get anything done.”

A broad coalition of Democrats and liberal advocacy groups insist that the measure should not be broken apart, arguing that now is the time for an ambitious overhaul. But with Senator Joe Manchin III, a conservative West Virginia Democrat, opposed to the measure in its current form, Democratic leaders and Mr. Biden face tough decisions in the coming weeks about whether they can wrangle all their members behind it more or less as is, or must consider striking a narrower compromise.

The margin for error is exceedingly thin: With Republican opposition unanimous, Democrats would not only need to hold all 50 of their senators together in favor of the bill but also persuade them to change the Senate rules to exempt it from the legislative filibuster, something Mr. Manchin and others have insisted they will not do under any circumstances.

“Right now, my focus is to keep this bill together as one package and get it through the committee,” Senator Amy Klobuchar, Democrat of Minnesota and the chairwoman of the Rules Committee, said in an interview.

Asked whether she might be willing to break the bill into pieces down the line, she declined to answer directly.

As currently written, the bill constitutes a sweeping liberal wish list that includes restoring voting rights to felons who have served their sentences, making it easier to register and vote, reining in undisclosed campaign donations, securing elections against cyberattacks and ending the partisan gerrymandering of congressional districts. It was drafted as a statement of Democratic values during the last Congress, at a time when Republicans controlled Washington and there was no chance it would be enacted.

Now, with Democrats in power — albeit by slim margins on Capitol Hill — they must transform a messaging bill into a viable piece of legislation.

The most visible hurdle to date is the apparent opposition of Mr. Manchin, who said last week that he opposed allowing the federal government to wade into election law, which is typically left to the states. He signaled that he would be unwilling to vote for any elections bill that was not bipartisan, much less provide the 50th vote needed to change the Senate rules to get past an all-but-certain Republican filibuster.

“Pushing through legislation of this magnitude on a partisan basis may garner short-term benefits, but will inevitably only exacerbate the distrust that millions of Americans harbor against the U.S. government,” Mr. Manchin said.

Behind the scenes, two election lawyers close to the White House and congressional Democrats said Mr. Manchin was not the only one on their side with reservations about the measure. They insisted on anonymity to discuss the concerns because few Democrats want to concede that there are cracks in the coalition backing the measure or incur the wrath of the legion of liberal advocacy groups that have made its enactment their top priority.

Black House members, for instance, are deeply uneasy over the bill’s shift to independent redistricting commissions, which they fear could cost them seats if majority-minority districts are broken up, particularly in the South. Before the bill passed the House, its authors spent significant time reassuring members of the Congressional Black Caucus that there were adequate protections in place to preserve their districts. But a prominent committee chairman, Representative Bennie Thompson of Mississippi, remained so concerned that he voted against the bill, despite having sponsored it.

Some fixtures of the party establishment believe the small-dollar public financing plan, which sets a six-to-one matching program for donations under $200, could incentivize and turbocharge primary challenges, particularly from the far left, by allowing them to cut into incumbents’ usual fund-raising edge more quickly.

Then there is a more vexing political concern, voiced most clearly by Mr. Manchin but shared by others, that after Mr. Trump spent months falsely claiming that Democrats were cheaters trying to rig the 2020 election against him, some independent voters — fairly or not — will view the legislation as an attempt to do just that and punish the party in the 2022 midterms.

State elections administrators have raised their own complaints, too, quietly lobbying their senators to modify national voting requirements they say would be onerous or impossible to put in place by 2022. Some have complained they were simply not consulted on a major federal rewrite of the system they believe they have overseen effectively.

“I’ve been saying that no election administrators were harmed in the making of this bill,” quipped Charles Stewart III, a leading expert on elections at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “Running elections is detail-intensive, and it’s not just shifting stuff around. You’re adding new features and adding complexity, not just shifting complexity from one place to another.”

Many say they support the goals of the proposal, but fear it overreaches in some places and issues contradictory orders in others. For instance, the legislation states that properly postmarked ballots that arrive as long as 10 days after an election must be counted as valid. But it also gives voters up to 10 days to correct mistakes on mailed-in ballots, meaning that late-arriving ballots with errors could delay certifying an election for up to 20 days. Some administrators believe that a 20-day lag threatens to cause havoc with schedules for formalizing election results.

Others say the measure, which requires all federal elections to start with an identical set of rules, ignores the reality in the scores of thousands of jurisdictions that oversee the vote. One Democratic state elections director said the early-voting mandates in the bill would require a county of 2,000 residents to keep polls open for 15 days, 10 hours a day, even for an off-year congressional primary that draws only a handful of voters.

Such an inflexible requirement, said the director, who spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of political repercussions, would create problems, not solve them.

There are practical challenges as well. The legislation’s security mandates for voting machines require that they meet the latest standards, issued so recently that machines that comply with them have yet to be manufactured. A grandfather clause would require the tiny federal Election Assistance Commission to certify and issue waivers for scores of thousands of machines, some dating to the 1990s.

And a provision requiring states to shift redistricting to independent commissions is supposed to be put in place for political maps drawn this year, a deadline officials say would be all but impossible to meet.

For now, many of the bill’s proponents — including dozens of groups focused on campaign finance, voting, gerrymandering and nearly every other liberal policy priority that would stand to benefit from Democratic control in Washington — have locked arms to insist the package cannot, under any circumstances, be broken up.

They say Democratic leaders are contemplating minor changes to placate elections administrators and have given them reason to believe that Mr. Manchin, a longtime proponent of campaign finance reform, will ultimately come around and support not only the bill but a narrow filibuster exemption to push it through on a simple majority vote once it becomes clear Republicans are unwilling to play ball.

“There is baseline commitment to keeping this bill together and passing it as it is,” said Fred Wertheimer, one of the most respected government watchdogs in Washington. “With 49 co-sponsors of this bill, it’s not a situation where one should be negotiating against themselves to satisfy the desires of opponents. We strongly support adopting this bill as whole, enacting it as whole and getting it signed into law as whole.”