In Washington, President Biden has committed to putting science and transparency above messaging, promising a hard break from the coronavirus policies of the Trump administration.

But in New York, things are moving in a different direction. Gov. Andrew Cuomo, just months after publishing a book about his leadership during the pandemic, acknowledged this week that his administration bore some responsibility for misrepresenting the death count in the state’s nursing homes.

The political fallout has been intense. And in an effort to stanch it, Cuomo is getting tangled up in battles with officials in his own party. Today, he singled out a Queens assemblyman, Ron Kim, who signed on to a letter in The New York Post that accused Cuomo of evading a federal investigation and of “intentional obstruction of justice.” Cuomo responded by using his Wednesday news briefing to accuse Kim of running a “racket” in accepting donations from nail-salon owners.

In an article by Jesse McKinley and Luis Ferré-Sadurní, who have been covering the scandal, Kim said that Cuomo had called him shortly after The Post published comments Kim had made criticizing Cuomo. On the call, Kim said, the governor threatened to “destroy” his career.

Jesse, our Albany bureau chief, has been covering the scandal over the death toll at nursing homes in a series of articles, and he took out some time to answer a few questions about how this all began — and the intraparty fights it’s stirring up.

Hi Jesse. Some members of the New York State Legislature have been talking about stripping Andrew Cuomo of his emergency powers, after his role in undercounting the virus deaths in New York’s nursing homes. Help catch us up.

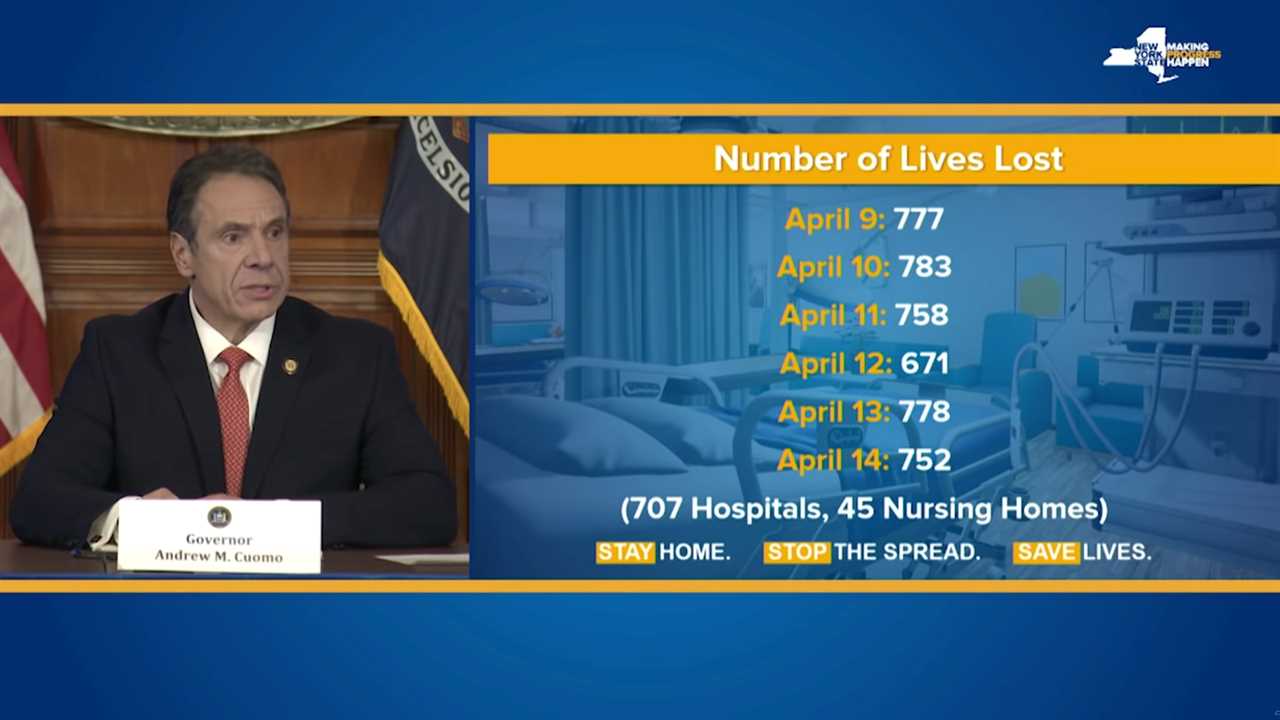

It’s a couple of things: The first issue is whether the state purposefully withheld data from the public, which seems indisputable at this point. In short, the state didn’t include hospital deaths in the count of nursing homes for nearly a year, and actively resisted efforts by lawmakers, the news media and outside groups to get that information. It used various excuses — a possible politically motivated federal investigation by the Trump Justice Department, the chaos of the pandemic, worry about bad data — but there’s no doubt that the state didn’t deliver the data until the past couple of weeks.

What’s also at issue, it seems, is something more esoteric, around Cuomo’s credibility and image. The governor got great reviews early in the pandemic, largely by saying he was the just-the-facts guy, the no-politics governor. This episode undercuts that in a big way.

It was the office of Letitia James, the state’s attorney general, whose politics are significantly to the left of Cuomo’s, that outlined the discrepancies. What is the status of Cuomo’s relationship with James, and is this just one example of a broader power struggle?

Hard to tell, but knowing the governor’s general us-versus-them approach to government, I would suspect that James won’t be invited to brunch at the mansion anytime soon. The force of her report was profound: causing the first big release of new, higher numbers, which in turn undercut the governor’s oft-repeated argument that the state’s nursing homes were doing better than most others’.

The surprising strength of James’s condemnation of the governor was particularly striking because the governor backed her and helped her first get elected in 2018. I’d be shocked if Cuomo was as supportive in 2022, when she’s up for re-election.

This scandal has earned Cuomo criticism from many members of his own party, particularly those on the left. What is this exposing about the loyalty that the savvy and cutthroat governor does, and doesn’t, enjoy from fellow Democrats in New York when push comes to shove?

The schism — between center and left — that has been percolating nationally in the Democratic Party is at a full boil in New York. The governor is not liked by many progressives in the state, who view him as an inveterate centrist who sometimes plays a progressive for the cameras. Cuomo rejects this, once even saying, “I am the left.” But that hasn’t convinced groups like the left-wing Working Families Party, which continues to wage war on Cuomo, including supporting his primary opponent, Cynthia Nixon, in 2018.

Which brings us to next year, when the governor will be up for a fourth term: He will, almost certainly, face a primary from that wing of the party. And this nursing home issue — his lack of transparency, his tendency toward heavy-handed, heavy-hitting governance — plays right into the progressive argument that Democrats need someone new in the State Capitol.

Just a few months ago, many observers were calling Cuomo a kind of heroic leader in the pandemic, framing him as a kind of foil to President Donald Trump. There were even murmurings of a possible position in Joe Biden’s cabinet. What lasting damage do you think the current scandal might do to his reputation?

Well, as with all things political in this day and age, it’s impossible to say what is going to stick to a public figure. Former President Donald Trump, after all, proved remarkably impervious to any number of scandals that might have sunk previous generations of politicians. But considering that Cuomo has staked a lot on his leadership — not to mention written a book about it — the optics of him not being forthcoming are not great.

He doesn’t seem to be backing down, either — stopping short of an actual apology this week and basically arguing that other people’s opinions were the problem, not the policy itself. That could read as principled, but could also read as arrogant or defensive, depending on your point of view. But one thing is certain: It didn’t put the story to bed.

How should we remember Rush Limbaugh?

Rush Limbaugh, who died today after a bout with lung cancer, will be remembered for more than just his brashly offensive persona and the white-hot invective that he dished out over more than three decades on the air.

Years before the rise of Fox News, Limbaugh played a big role in altering people’s “senses of what conservatives could say,” said Brian Rosenwald, the author of “Talk Radio’s America: How an Industry Took Over a Political Party That Took Over the United States.”

“It was misogynistic, it was racist, it was anti-L.G.B.T.Q.,” Rosenwald said of Limbaugh’s on-air persona. “But the fact is that he was also a phenomenal talent, and also a phenomenal entertainer, and phenomenal at reaching out of the radio and grabbing someone and keeping you listening in your driveway.”

In the process of helping to invent the shock-jock format, Limbaugh also reshaped the way much of the country talks about politics. He developed a following in California in the 1980s, when his on-air bits included ridiculing those who died from AIDS while a Dionne Warwick power ballad played in the background, and stridently trumpeting his opposition to feminism. (In a rare move, he later apologized for his “AIDS Updates” in particular.)

He helped guide conservative media into a more pugilistic and aggressive era, voicing the id of his heavily white following as the United States stepped into a more diverse and less financially secure 21st century. The rise of the Tea Party in the early 2010s, and then of Donald Trump’s political fortunes a few years later, appeared to vindicate Limbaugh’s approach, one that fully exposed the entertainment value of conservative angst.

The day after Limbaugh announced his cancer diagnosis last year, Trump awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor.

In the mid-1980s, Limbaugh’s success came as a shock unto itself, at a time when the superior fidelity of FM radio had moved most music programming to that side of the dial and talk-show hosts were grasping for new ways to keep listeners engaged.

“Rush upended the model for what talk radio was,” Rosenwald said, speaking by phone shortly after the news broke of Limbaugh’s death. “They thought it had to be local and centered around callers and interviewers. He does this national content, no one has ever heard a show like his — and he’s wildly successful.”

Controversy paved Limbaugh’s way across America, as his show was syndicated by more stations in the 1980s and ’90s. “The first few weeks a station would put him on the air the station would always get calls: ‘Who is this guy? He’s terrible. Get him off the air!’” Rosenwald said. “Within a few weeks, the calls would change.”

What also bears remembering is the vast amount of money Limbaugh made in the process — not only for himself, but also for the entire AM radio industry, which had seemed to be in terminal decline.

“Anyone in the business — liberal, conservative, moderate — will tell you that he saved AM radio,” Rosenwald said.

“He made hundreds of millions of dollars from his success,” he added. “And there are countless careers that wouldn’t have existed but for Rush Limbaugh.”

Nowadays you could argue that statement applies to jobs well beyond the radio — in TV news and the internet, too.