One of Washington’s leading conservative constitutional lawyers publicly broke on Sunday with the main Republican argument against convicting former President Donald J. Trump in his impeachment trial, asserting that an ex-president can indeed be tried for high crimes and misdemeanors.

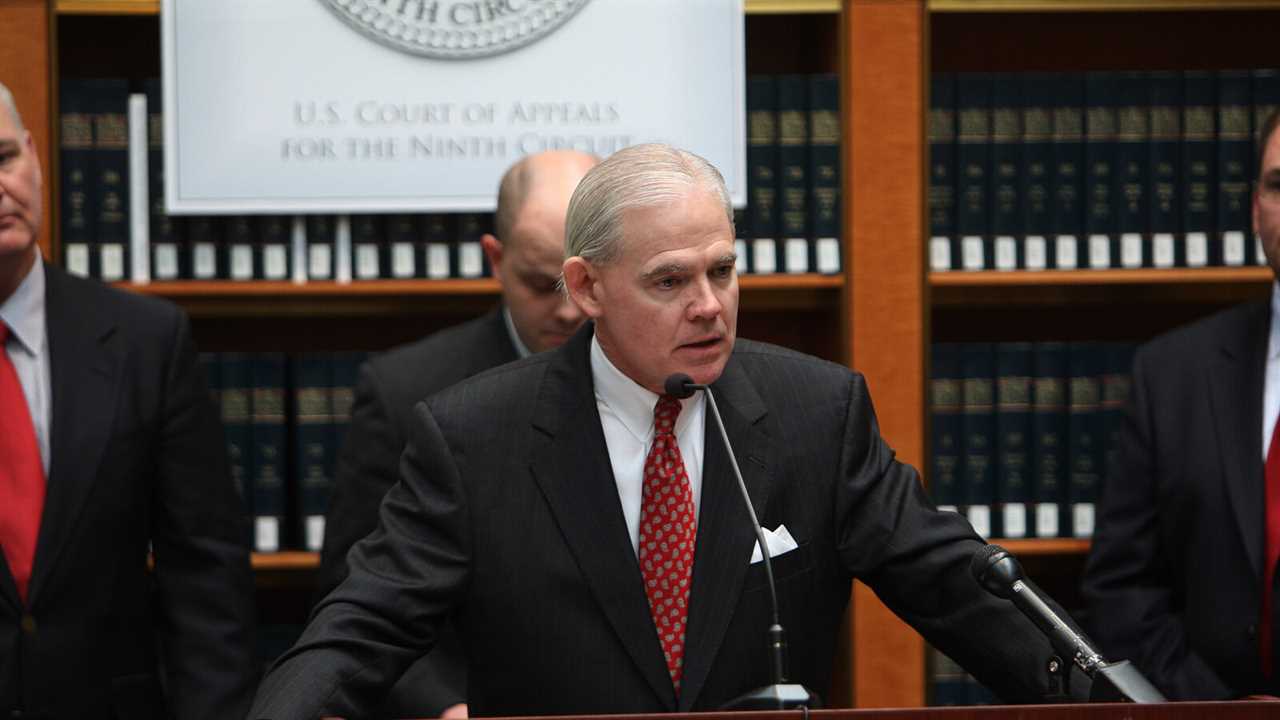

In an opinion piece posted on The Wall Street Journal’s website, the lawyer, Charles J. Cooper, who is closely allied with top Republicans in Congress, dismissed as illogical the claim that it is unconstitutional to hold an impeachment trial for a former president. The piece came two days before the Senate was set to start the proceeding, in which Mr. Trump is charged with “incitement of insurrection” in connection with the deadly assault on the Capitol by his supporters on Jan. 6.

Since the rampage, Republicans have made little effort to excuse Mr. Trump’s conduct, but have coalesced behind the legal argument about constitutionality as their rationale for why he should not be tried, much less convicted. Their theory is that because the Constitution’s penalty for an impeachment conviction is removal from office, it was never intended to apply to a former president, who is no longer in office.

Many legal scholars disagree, and the Senate has previously held an impeachment trial of a former official — though never a former president. But 45 Republican senators, including Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, the minority leader who is said to believe that Mr. Trump committed impeachable offenses, voted last month to dismiss the trial as unconstitutional on those grounds.

Mr. Cooper said they were misreading the Constitution.

“The provision cuts their interpretation,” he wrote. He argued that because the Constitution allows the Senate to bar officials convicted of impeachable offenses from holding public office again in the future, “it defies logic to suggest that the Senate is prohibited from trying and convicting former officeholders.”

Mr. Cooper’s decision to take on the argument was particularly significant because of his standing in conservative legal circles. He was a close confidant and adviser to Senate Republicans, like Ted Cruz of Texas when he ran for president, and represented House Republicans — including the minority leader, Representative Kevin McCarthy of California — in a lawsuit against Speaker Nancy Pelosi. He is also the lawyer for conservative stalwarts like John R. Bolton and Jeff Sessions, and over his career defended California’s same-sex marriage ban and had been a top outside lawyer for the National Rifle Association.

But Mr. Cooper, who is said to be dismayed by the unwillingness of House and Senate Republicans to hold Mr. Trump accountable, took on the main claim made by his own confidants and clients, offering a series of scholarly and technical arguments for why the Constitution allows for a former president to stand trial.

It was unclear whether Mr. Cooper’s opinion would have any influence on the outcome of the trial. It could provide cover to Republican senators open to convicting Mr. Trump who were caught off guard by last month’s vote, forced by Senator Rand Paul of Kentucky, to effectively dismiss the case as unconstitutional. Some Republicans have since said they did not necessarily mean to signal that they were opposed to hearing the case, or had made up their minds about Mr. Trump’s guilt.

Seventeen Republicans would have to join with all 50 Democrats to reach the two-thirds threshold necessary to convict Mr. Trump — something that appears to be exceedingly unlikely.

But Mr. Cooper seemed to be working to change minds. He wrote in his opinion piece that in the short time since the vote, legal experts’ understanding of the issue had evolved and “exposed the serious weakness of Mr. Paul’s analysis.”

“The senators who supported Mr. Paul’s motion,” he wrote, “should reconsider their view and judge the former president’s misconduct on the merits.”

The question of constitutionality could come to a head quickly when the trial opens on Tuesday. Though Senate leaders were still debating the precise structure of the trial, prosecutors and Mr. Trump’s defense team were preparing for the possibility that Mr. Paul or another senator could force a second vote on the question on the opening day, before either side gets into their full presentations.

Mr. Cooper has a deep and long history in the conservative legal movement. He grew up in Alabama, and despite not attending an Ivy League law school, landed a clerkship for Justice William H. Rehnquist in 1978 before he became the chief justice, and at a time when Justice Rehnquist was considered the most conservative member of the court.

Mr. Cooper went on to become the head of the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel during the Reagan administration, writing several highly conservative and controversial interpretations of the law, including one about whether employers could decline to hire someone who may have AIDS.

As a private lawyer, he has defended issues like school prayer and was an active member in the Federalist Society. In 2010, when the Republican National Lawyers Association named him the Republican lawyer of the year, there were three speakers for Mr. Cooper: Mr. Bolton; the head of the N.R.A., Wayne LaPierre; and Ed Meese, an attorney general under Ronald Reagan who was considered among the most conservative in the department’s history.

In the early days of the Trump administration, Mr. Cooper — who is longtime friends with Mr. Sessions — was considered to be the solicitor general. But Mr. Cooper remained in private practice, becoming the lawyer for Mr. Sessions as he was enmeshed in controversy related to the Russia investigation. In the second half of the Trump presidency, Mr. Cooper represented Mr. Bolton and his deputy, Charles Kupperman, in the first impeachment trial of Mr. Trump.

Mr. Cooper has continued to represent Mr. Bolton as the Justice Department has sued him to recoup money he made from a damning book he published about Mr. Trump.

Nicholas Fandos contributed reporting.

Did you miss our previous article...

https://trendinginthenews.com/usa-politics/biden-wants-harris-to-have-a-major-role-what-it-is-hasnt-been-defined