President Biden mentions it in private calls. The White House reads its work. And Senator Chuck Schumer, the majority leader, teams up with its leaders for news conferences, blog posts and legislation.

The embrace of Data for Progress by the highest ranks of the Democratic Party is a coming-of-age moment for a left-leaning polling firm and think tank that is barely three years old.

This week, legislation that was championed by the group and that would pour nearly a quarter-trillion dollars into scientific research and development passed the Senate. Earlier this year, Julian Brave NoiseCat, vice president of policy and strategy, led a successful campaign to nominate and confirm Deb Haaland as the first Native American cabinet secretary.

Part of the group’s early success reflects a Democratic Party that shifted to the left during the Trump era. But it also signifies the maturing of a new generation of liberal activists, who are grappling with how to wield political power when they’re no longer the opposition.

For Data for Progress, the strategy is Politics 101: Politicians like policies that are popular.

“The secret sauce here is that we’ve developed a currency that they’re interested in,” says Sean McElwee, the executive director of the group. “We get access to a lot of offices because everyone wants to learn about the numbers.”

The big “secret”? Polling data that’s targeted, cheap and fairly accurate.

Aides to Democratic congressional leaders say Data for Progress can quickly poll on policies — like expanding the Child Care Tax Credit or unemployment benefits, or spending $400 billion on senior care — that would be considered too specific for a full survey by some other polling firms. And by finding ways to do operations that pollsters traditionally outsource, the organization can charge tens of thousands of dollars less than more established firms, according to Mr. McElwee.

Data for Progress then uses those quick-turnaround surveys to push its version of a progressive agenda, boosting liberal candidates in primaries and persuading Democrats to rally around popular liberal policies once in office.

It doesn’t hurt that Mr. McElwee has a talent for self-promotion.

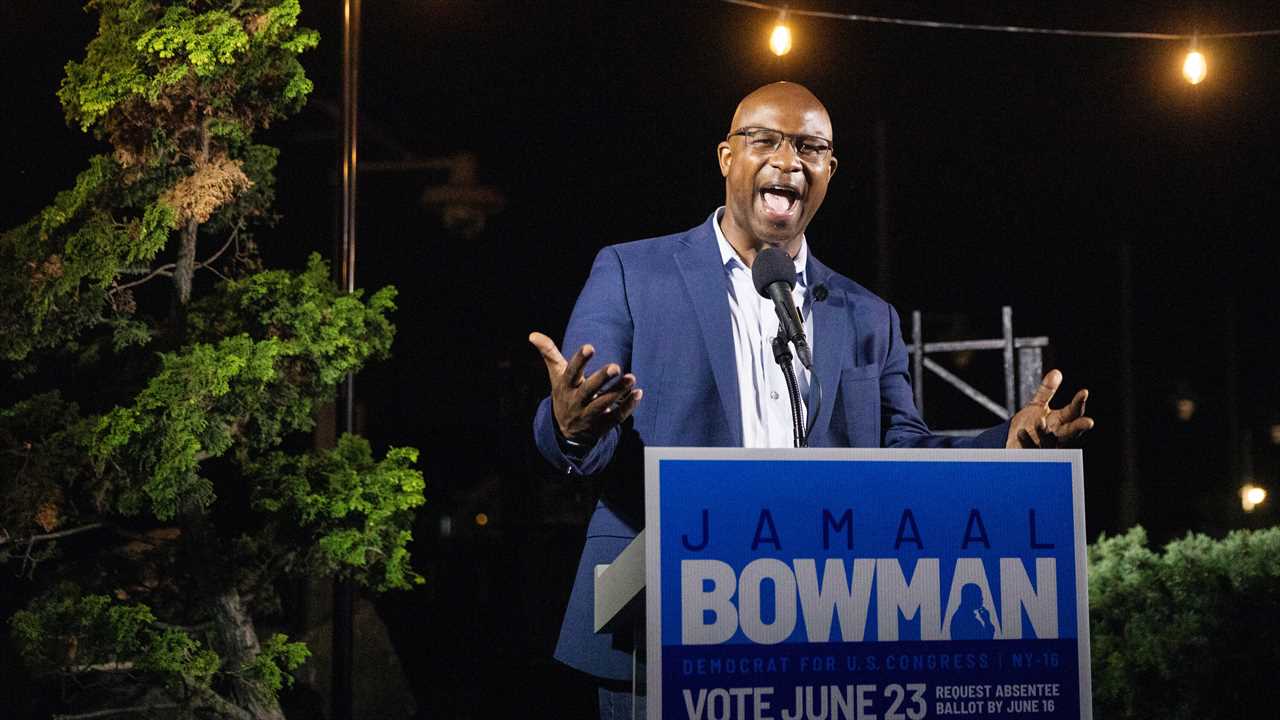

“Does anyone put out polls to push media narratives more effectively than @SeanMcElwee,” quipped my colleague Shane Goldmacher last summer, after a Data for Progress survey that showed Jamaal Bowman, a client of the group, leading his primary race prompted an influx of liberal donations and energy into his campaign to defeat a longtime congressman in New York.

For his part, Mr. McElwee, 28, once described himself as “Radiohead for donors — you can’t really explain why I’m good but everyone knows that I’m good at it.” (Data for Progress is funded by a mix of private donations, paid polling work and support from foundations that back its policy research on issues like climate change.)

Of course, for many political activists, strategists and officials, leveraging approval ratings to push an agenda is a pretty basic political strategy. But in a world of young progressive activists who often argue that a central goal is to bring left-wing ideas from the fringes into the mainstream, the Data for Progress approach can be controversial, criticized in some quarters as shrinking expectations and selling out a bolder vision of racial justice and economic equality to appeal to wealthier and more moderate voters.

“Imagine Sean McElwee giving a keynote address at the Walmart Center for Racial Equity — forever,” wrote Matt Karp, a history professor at Princeton and a contributor to the liberal magazine Jacobin, warning of a left that gives away too much of its agenda to a “corporate Democratic Party.”

Mr. McElwee and his organization, which now employs nearly two dozen data scientists, policy experts and communication aides, say spending their political capital now that Democrats control Washington is kind of the point.

“The point of being a progressive and being involved in politics is to make progress happen,” said NoiseCat, an activist and author who was Data for Progress’s first employee. “At a certain point progress should mean we got x and y thing done that made people’s lives better. I think it’s kind of ironic that a lot of progressives forget that the main point is we’re supposed to do the progress thing.”

Over the past three years, Mr. McElwee made his own shift from self-described “Overton Window mover” to a more pragmatic approach, coming to embrace Mr. Biden — “I don’t like him very much,” he said in 2019 before meeting with his campaign less than a year later — and moving away from calls to #AbolishICE, a slogan he helped popularize that became a rallying call for the left in 2018. (Only about a quarter of voters backed the idea of eliminating Immigration and Customs Enforcement, according to polling at the time.)

Now, his group advocates what Mr. McElwee has called a “normie progressive theory of change,” backing liberal candidates who can build broad coalitions around popular policies. Think lawmakers like Representative Lauren Underwood, who flipped her suburban Illinois district, rather than more firebrand progressive leaders like Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

On policy, they’ve come to embrace what they believe are the most popular parts of a liberal agenda as a way of persuading voters who might be skeptical of bolder rhetoric. Emphasizing a clean electric standard, instead of a carbon tax, for example. Or focusing on passing Mr. Biden’s agenda through reconciliation rather than fighting over abolishing the filibuster, a proposal that currently lacks sufficient support among Senate Democrats.

Data for Progress is also trying to move more into electoral politics, hoping to expand its list of campaign clients beyond Senator Elizabeth Warren’s re-election race and the Senate campaign of John Fetterman, Pennsylvania’s lieutenant governor and one of the state’s most prominent Democrats.

“We’re relatively young, but my belief about progressive politics is that first and foremost we have a moral obligation to win,” Mr. McElwee said. “The demands in a lot of corners for policymakers to hold positions that are highly unpopular is wrong.”

Drop us a line!

By the numbers: 17

… That’s the percentage of people in 16 countries who think democracy in the U.S. is a good example for other nations to follow, according to a new survey conducted by Pew Research Center.

… Seriously

Fridgegate and calls to release E-ZPass records: Whatta town!

Did you miss our previous article...

https://trendinginthenews.com/usa-politics/garland-confronts-longbuilding-crisis-over-leak-inquiries-and-journalism