WASHINGTON — The new infrastructure law signed by President Biden includes almost $50 billion to protect communities against climate change, the largest such investment in United States history and a recognition that the effects of warming are outpacing America’s ability to cope.

Mr. Biden has insisted that at least 40 percent of the benefits of federal climate spending will reach underserved places, which tend to be low income, rural, communities of color, or some combination of the three.

But historically, it is wealthier, white communities — with both high property values and the resources to apply to competitive programs — that receive the bulk of federal grants. And policy experts say it’s unclear whether, and how quickly, federal bureaucracy can level the playing field.

“These tensions have to be squarely faced,” said Xavier de Souza Briggs, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution who volunteered on Mr. Biden’s transition team. The White House “is trying to transform some of these deep structures of government that have needed attention for a long, long time,” he said.

Some local governments have tried to distribute money for climate resilience in a more equitable manner. But the political backlash can be fierce.

After Hurricane Harvey devastated Houston in 2017, voters approved a $2.5 billion bond to fund more than 500 flood-control projects around the county. Officials decided to prioritize those projects based in part on the “social vulnerability” of the communities they protected — an index that includes the percentage of residents who are minorities.

Residents in wealthier neighborhoods, along with their elected representatives, complained the policy would push their communities to the back of the line.

The new climate provisions in the infrastructure bill inject billions of dollars into competitive grant programs. These are pots of money that towns, cities and counties can access only by submitting applications, which federal agencies then rank, with funds going to applicants with the highest scores.

That system is designed to ensure that funding goes to the most worthwhile projects.

But it also hinges on something outside the control of the federal government: The ability of local officials to use sophisticated tools and resources to write successful applications. The result is a process that has widened the gap between rich communities and their less affluent counterparts, experts say.

‘What good is it?’

The disparity begins even before the application process begins. That’s because local governments must be aware of the grant programs in the first place, which means having dedicated staff to track those programs. Then they need to design proposals that will score highly, and correctly complete the reams of required paperwork.

Even if they are awarded a grant, communities are required to pay a share of the project — often 25 percent, which is unaffordable for many struggling towns and counties.

Governments that can clear those obstacles face a final hurdle: Demonstrating that the value of the property that would be protected is greater than the cost of the project. That rule often excludes communities of color and rural areas, where property values are usually lower than in white communities.

“We have counties and municipalities that do not have the institutional capacity to participate in this alphabet list of programs that the federal government has created for hazard mitigation and climate adaptation,” said Jesse Keenan, a professor at Tulane University who focuses on how governments try to cope with global warming.

During a virtual meeting in October, advocates challenged senior White House officials to explain how they would fulfill their promises of racial equity, given the history of federal grant programs.

“It’s one thing to have an idea of how to build back better,” said Beverly Wright, founder and executive director of the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice. “But if the people who need it the most can’t afford it, what good is it?”

Yoca Arditi-Rocha is executive director of the CLEO Institute, a nonprofit group in Florida that promotes climate change education, advocacy and resilience, especially for low-income communities.

“The price tag to adapt to the significant climate risk our communities are facing is truly enormous,” she said. “To build back better, the federal government cannot leave behind communities like my own.”

Officials conceded the challenge, and said they were looking for ways to address it, without giving specifics. “We’re very aware that this is an issue that needs work,” said Candace Vahlsing, associate director for climate at the White House Office of Management and Budget.

‘If this grant doesn’t qualify, then I’m not sure what would’

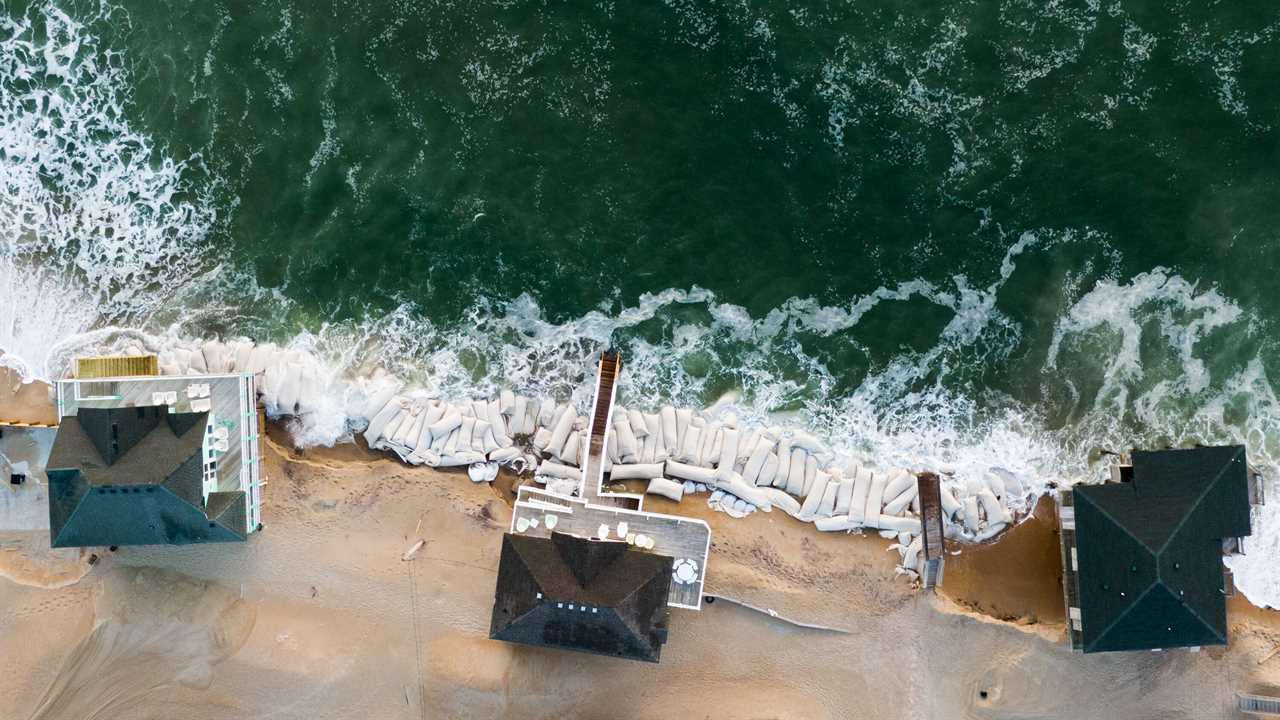

The consequences of the current approach were on display this past summer, when the Federal Emergency Management Agency named the first round of likely winners under a new climate-resilience grant program, funding projects to address future risks from flooding, wildfires and other hazards.

The Biden administration has touted the program, called Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities, or BRIC, as a model that should be expanded. The infrastructure bill provides billions more to the program.

But most of the first round winners were wealthy, predominantly white areas in a handful of coastal states, federal data show.

More than half the money went to California, New Jersey and Washington State. The largest single recipient was a $68 million flood-control project in Menlo Park, Calif., where the median household income is more than $160,000, the typical home costs more than $2 million and only one in five residents are Black or Hispanic. The project is in line to get $50 million from FEMA.

By contrast, FEMA rejected applications from places like Smithland, Ky., a town of just 240 people where the Cumberland and Ohio Rivers meet, halfway between St. Louis and Nashville. The town sought $1.4 million to build a levee along the riverbank, which has crested at flood levels three times in the past 10 years.

“That’s a lot of money for us,” said Garrett Gruber, the top elected official in Livingston County, which includes Smithland.

But he said the cost for the barrier, though large compared with the value of the houses it would protect, would be less expensive than erecting temporary barriers every time the river crests.

“If this grant doesn’t qualify, then I’m not sure what would,” Mr. Gruber added. “It’s almost as if you would rather me just evacuate the city.”

The rules that governed the first round of BRIC awards were set under the Trump administration. A senior official in the Biden administration, who spoke on condition that he not be identified by name, noted that the rules for the next round of awards have been changed, giving extra points for applications that cite benefits for disadvantaged communities.

That’s part of the Biden administration’s “Justice 40” initiative, which calls for disadvantaged communities to receive the “overall benefits” of 40 percent of climate dollars, as defined and calculated by each federal agency. The initiative does not require a specific portion of climate funding be spent in underserved communities.

The new rules for the FEMA program define disadvantaged communities broadly, to reflect one or more of 15 suggested criteria. They include persistent poverty; racial segregation; high costs for housing, transportation, energy or water; “linguistic isolation”; job losses related to the transition away from fossil fuels; “disproportionate impacts from climate”; or even limited access to health care.

And to be successful, communities must still demonstrate that their infrastructure projects would save more money than they would cost, the same criteria that makes it hard for climate resilience projects in low-income communities to get approved.

Protecting property or people

One way to help small or low-income communities would be to draw from history, according to Ellory Monks, who runs a website called The Atlas, where local officials can share information.

Ms. Monks has called for the federal government to recreate a version of circuit riding, in which judges traveled between small towns during the 1800s. Federal agencies would assign staff to work and live in towns or counties for a period, to help local leaders devise resilience projects and then apply for funding.

“You just can’t do that from D.C.,” Ms. Monks said.

If the government really wants to help disadvantaged communities become more resilient to climate change, it should move away from competitive grant programs altogether and instead decide which communities need help, then provide it directly, according to Carlos Martín, a fellow at Brookings.

“Places that we know have high exposure to climate-related effects, and that have low wealth,” Mr. Martín said. “These are easy criteria we could set up.”

Whatever approach it uses, the Biden administration must rethink who gets climate resilience money, said Ms. Arditi-Rocha of the CLEO Institute. “What is most important?” she said. “Protecting property values, or protecting the lives of people?”