WASHINGTON — In the hours before Lance Cpl. Jared Schmitz, 20, was killed by a terrorist’s bomb in Afghanistan, he posed for a photograph taken by a bunkmate. In the image, the Marine’s brow was furrowed. He flashed a peace sign.

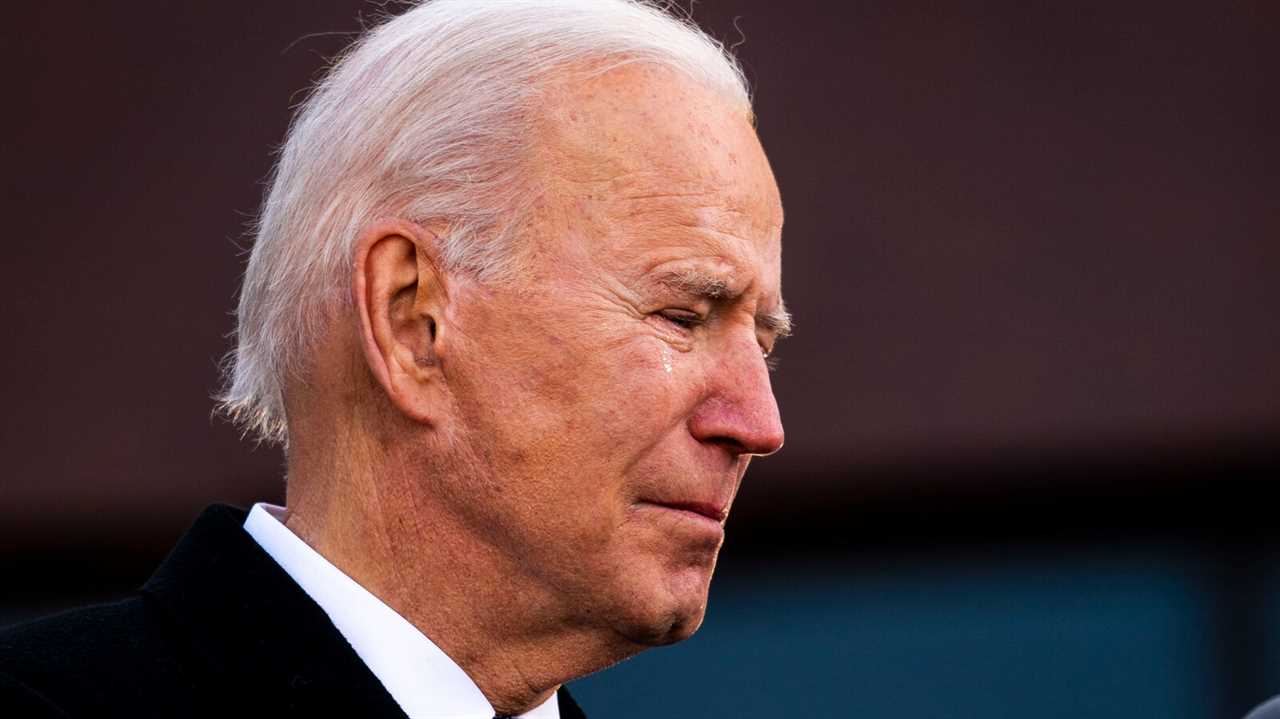

“This is Jared Schmitz,” his father, Mark Schmitz, said he told President Biden days later at Dover Air Force Base, where the two men had traveled to observe the dignified transfer of the remains of 13 U.S. Marines killed last week in the attack in Kabul. “Don’t forget his name.”

But Mr. Schmitz was confused by what happened next: The president turned the conversation to his oldest son, Beau, who died of brain cancer in 2015. Referring to him has become a reliable constant of Mr. Biden’s presidency. In speeches, Oval Office discussions and personal asides, Mr. Biden tends to find a common thread back to his son, no matter the topic. But for Mr. Schmitz, another father consumed by his grief, it was “too much” to bear.

“I respect anybody that lost somebody,” Mr. Schmitz added in an interview, “but it wasn’t an appropriate time.”

The Biden administration, seeking to avoid a public rift with Gold Star families, has not pushed back on criticism from Mr. Schmitz and other families who have said the president brought up his own son too often and acted distant during the ceremony at Dover. But the moment crystallized just how much Mr. Biden is still haunted by the memory of a son he had always described to confidants as “me, but without all the downsides,” and how his anguish over that loss can clash with the political realities of being president.

Mr. Biden’s reputation is staked, in part, around his ability to withstand soul-shattering tragedies. His first wife, Neilia, and his infant daughter, Naomi, were killed in a car accident in 1972. But it was Beau’s death that left the people in Mr. Biden’s life wondering if he would ever recover, let alone wage a third bid for the presidency. His son, they say, is a major reason he decided to stay in public life.

“He is a relentlessly optimistic person,” said Shailagh Murray, a former adviser of Mr. Biden’s, “and in many respects, Beau was the human embodiment of that optimism.”

The president still sometimes mentions his son in the present tense in private discussions, according to people who have spoken with him. He carries his son’s rosary beads with him, once holding them aloft during a virtual meeting at the White House this spring with the president of Mexico. Several people close to Mr. Biden conceded that he sometimes does not always seem to be aware that broaching his own loss can make others uncomfortable.

But, of his rocky reception with some families at Dover, Ms. Murray said, “I’m sure he understands the reaction he got better than a lot of people.”

In his public meetings with world leaders, doctors, military officials and families, Mr. Biden often shares how his experience with his son’s deployment to Iraq or battle with brain cancer affected his family. Invoking Beau’s memory amid the violent collapse of Afghanistan, to result of the most politically volatile decision of his presidency to date, provided a rare moment for critics to pounce on a penchant for eulogizing his son.

“Mr. Biden is not a Gold Star father and should stop playing one on TV,” William McGurn, a speechwriter for President George W. Bush, wrote in an op-ed in The Wall Street Journal. Mr. Biden has never claimed that his son died in combat, but he has often spoken of his son’s overseas deployment and the toll it took on his family. Mr. Biden’s supporters say that military families are entitled to their grief, but that the president is also entitled to his.

“The families who are grieving, they are free to feel however they feel,” Fred Guttenberg, whose 14-year-old daughter, Jaime, was killed in a mass shooting in 2018 at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla., and who has received periodic calls from Mr. Biden, said in an interview. “But to anyone else who may have been critiquing: The president’s children, those living and those not, they formed who the president is.”

They have also influenced Mr. Biden’s presidency from the start. In January, before Mr. Biden left Delaware for Washington, he told his advisers that he wanted to deliver a farewell speech at the Delaware National Guard headquarters. It is a building named for his son.

“I only have one regret,” Mr. Biden said as he gave tearful remarks that day. “That he’s not here, because we should be introducing him as president.”

As commander in chief, Mr. Biden is without a critical political adviser whose advice he trusted more than almost anyone else’s. He talks daily to his other children, Hunter and Ashley, aides said, but he used to speak to his oldest as many as four times a day, comparing notes and discussing next moves.

They were each other’s primary sounding boards, especially when it came to political and messaging strategy. And Beau, who was attorney general of Delaware, was considered the heir apparent of the Biden political brand. He was calm and intelligent, with a self-deprecating sense of humor. Like his father, he tended to be an idealist.

“He was Biden 2.0,” Ted Kaufman, a friend and adviser, said. “They were father and son. They happened to be in the same business.”

Before Beau became sick, he talked to his confidants about running for governor of Delaware and, from there, possibly running for the presidency.

“He was a person of such tremendous integrity to a point where it’s as if he wouldn’t dare jaywalk,” said Louis D. Lappen, a deputy U.S. attorney who worked closely with Beau. “I’m certain that when he has his toughest decisions to make,” he said of the president, “that he has conversations in his mind with Beau.”

When it came to picking key jobs in his administration, Mr. Biden installed several officials who were former rivals, but were also people his son had liked or admired. He has said Pete Buttigieg, the transportation secretary, reminds him of Beau.

Vice President Kamala Harris served as attorney general of California at the same time Beau served in the same position in Delaware. At one point, Ms. Harris has said, they spoke daily. That experience became an asset when Mr. Biden was assessing his running mates.

“I know how much Beau respected Kamala and her work, and that mattered a lot to me, to be honest with you, as I made this decision,” Mr. Biden said last summer in announcing his selection. “There is no one’s opinion I valued more than Beau’s.”

Beau had also known Lloyd J. Austin III, the retired general who is now Mr. Biden’s defense secretary, from his time in the Army National Guard in Iraq. Mr. Austin, who is Catholic, would sit next to Beau during Mass. And several of Beau’s former aides were dotted across the Biden transition teams after Mr. Biden’s election.

The general thinking among Mr. Biden’s supporters is that he is a welcome change from President Donald J. Trump, who was almost always publicly unable to express empathy. They believe Mr. Biden is the right president for this moment in history, one so far marked by the unthinkable loss caused by the coronavirus pandemic and images of human desperation that accompanied a violent end to America’s longest war — an ending that has been politically costly but one Mr. Biden has staunchly defended, often in the context of refusing to send more of America’s sons and daughters to war.

“He obviously has learned a lot about what it means to mourn and what it means to grieve,” said Representative Jamie Raskin, Democrat of Maryland, who received a call from Mr. Biden days after his son, Tommy, killed himself on New Year’s Eve last year.

Mr. Raskin said that he had been in such anguish that he had barely been able to speak, but the president’s hard-won assurance that the passage of time would begin to heal his family’s pain offered a small degree of comfort.

“People can obviously have different reactions to that,” Mr. Raskin said, “but we found it enormously consoling.”

Mr. Raskin and others who have encountered Mr. Biden in the depths of their grief said that Beau had come up frequently and at length. Mr. Guttenberg said that the president called him out of the blue about a week after his daughter’s death, and during that conversation, he spoke about Beau.

“He wanted to talk to me about his kids,” Mr. Guttenberg said, “but in a weird way it was also so that I would talk to him about my kids. It was his way of saying, ‘We have a bond here, and you can be comfortable with me.’”

But Mr. Biden’s advisers privately acknowledge that not everyone responds in the same way, and he does not always adjust his approach depending on the audience.

Mr. Schmitz, the father of the young Marine who died in Afghanistan, said that in the past week, he had looked for opportunities to tell anyone who would listen about who his son was. His son Jared, he said, had been proud to be a Marine in a Navy family and had wanted to serve in Afghanistan for a chance to help people there. He wants the world to know his son was a hero.

“I wanted to make sure that people that didn’t know him had a chance to know a little piece of him,” he said. “These guys are amazing human beings.”

Mr. Schmitz said he was contacted by military officials again this week and asked if he would be open to receiving a phone call from Mr. Biden. He declined.