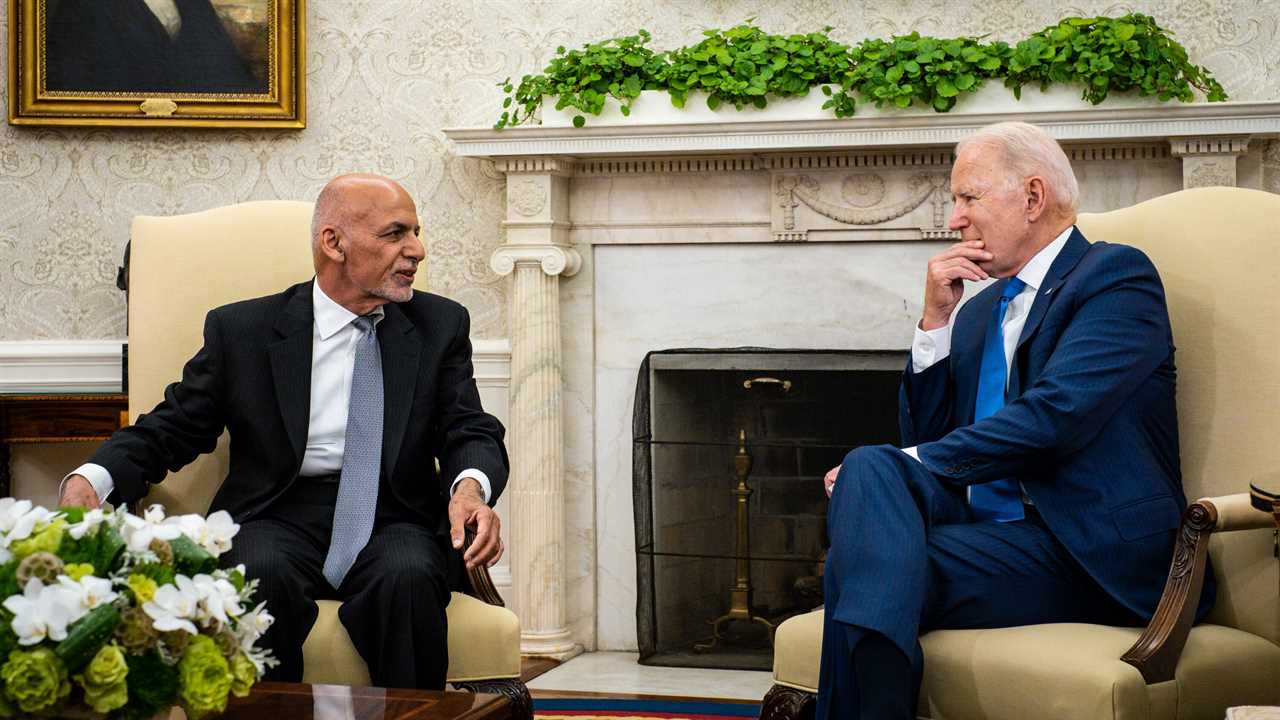

WASHINGTON — President Biden said Friday that the future of Afghanistan was in its own hands, but he promised its president, Ashraf Ghani, that the United States would support the country even after American forces withdraw following nearly 20 years of war.

During a visit to Washington by Mr. Ghani and Abdullah Abdullah, Afghanistan’s chairman of the High Council for National Reconciliation, Mr. Biden said the United States would continue to offer security assistance, as well as diplomatic and humanitarian aid.

But his message was clear: The U.S. military is leaving.

“Afghans are going to have to decide their future, what they want,” Mr. Biden said at the White House. “The senseless violence has to stop.”

His decision to pull out American troops by Sept. 11 is one of the most consequential of his presidency so far, a deeply personal calculation that comes “from the gut,” as one official put it. And despite the worsening security situation, gloomy intelligence reports and the likelihood the White House will face terrible images of human suffering and loss in the coming weeks and months, Mr. Biden has vowed to withdraw regardless of the conditions on the ground.

Those conditions are increasingly dire.

While military planners and intelligence analysts have long had differing assessments on Afghanistan’s prospects, they have come to a consensus that Mr. Ghani’s government could fall in as few as six months, according to officials briefed on the intelligence work. They cite recent setbacks by Afghanistan’s security forces, including the defeat of an elite commando unit.

Still, for Mr. Ghani, the meeting at the White House was a chance to show he still had financial backing from the West, even without a U.S. military presence.

“We are fully satisfied that this decision has been taken in the spirit in which it was offered, which is not abandonment of Afghanistan,” Mr. Ghani told reporters at a news conference afterward. “This is a new chapter in our relationship.”

Since May 1, when U.S. forces officially began their withdrawal, the Taliban swept across the north, toppling dozens of districts in a part of the country that has long been considered a stronghold against the insurgent group.

Mr. Ghani described the challenge his government was facing as the Taliban gain more territory, comparing the situation to the Union fighting off the Confederacy in 1861.

“Rallying to the defense of the republic, determined the republic is defended — it’s a choice of values,” Mr. Ghani said, adding that Afghan security forces had retaken six districts on Friday. “The values of an exclusionary system or an inclusionary system. We’re determined to have unity, coherence, national sense of sacrifice and will not spare anything.”

The Taliban, on the other hand, seem increasingly intent on achieving a military victory as peace talks in Doha, Qatar, remained stalled.

As U.S. air support wanes, the Afghan security forces remain largely demoralized, reliant on their elite commando forces to retake territory and their air force — plagued with burned out pilots and growing mechanical issues — to resupply and evacuate the quickly shrinking constellation of checkpoints, outposts and bases across the country.

Mr. Biden, however, remains resolute in his choice. According to an Associated Press/NORC poll last year, only 12 percent of Americans said they were closely following news related to the U.S. presence in Afghanistan.

Administration officials said at least three major factors had influenced Mr. Biden’s calculus. First was the strong likelihood that the peace talks in Doha between the Taliban and the Afghan government would not succeed. That was largely preordained by the Trump administration’s failure to hold the Taliban accountable to the terms of the deal signed in February 2020, administration officials said. By the time Mr. Biden took office, the United States had already drawn down to about 3,500 troops, and the Taliban had seized the momentum on the battlefield, with little incentive to bargain.

Given that, the second major factor was that if the United States did not honor the peace agreement and left, any remaining U.S. forces would come under attack — an outcome the Taliban had generally avoided after signing the deal. Under the new scenario, American air power could keep the Taliban, as well as Al Qaeda and the Islamic State, at bay, but there would be no clear political end in sight to a campaign that American commanders concluded long ago could not be won by military might alone.

“The president made his decision, which is consistent with his view that this was not a winnable war, to bring the U.S. troops home after 20 years of fighting this war,” the White House press secretary, Jen Psaki, said on Friday. “A big part of that decision was also around the fact that if we left our troops there, our troops would be at risk of the Taliban shooting them by May 1.”

Finally, American intelligence officials told Mr. Biden that the threat Al Qaeda and the Islamic State posed to the United States homeland had been greatly diminished — and was likely to take at least two years to reconstitute.

To keep that threat in check, the Pentagon already has stationed armed MQ-9 Reaper drones at bases in the Persian Gulf to keep watch. But finding hostile targets on the ground will be much more difficult without Afghan government troops and spies to help identify them, and the risk of accidental civilian casualties from American airstrikes will increase, commanders warn.

The Biden administration has assured Mr. Ghani with financial support, including $266 million in humanitarian aid and $3.3 billion in security assistance, as well as three million doses of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine and oxygen supplies. In Afghanistan, efforts to address a third wave of the coronavirus have been hampered by fighting in the area.

A small embassy security force will also stay behind in Afghanistan.

The administration will also soon begin relocating “a group of interpreters and translators, as well as other at risk categories who have assisted us,” Ms. Psaki said on Friday. She later confirmed in a statement that those who were in the pipeline for visas but had already fled Afghanistan for fear of retaliation would still be eligible.

But the White House is bracing for a long, difficult summer.

“You don’t fight and die with your Afghan partners for 20 years and then just pull the rug out from under them,” said Lisa Curtis, the senior director for South and Central Asia at the National Security Council under the Trump administration. “Everyone understands the need to withdraw our troops but there’s also a need to do it responsibly and in a way that gives the Afghans a fighting chance.”

Zolan Kanno-Youngs and Eric Schmitt reported from Washington, and Thomas Gibbons-Neff from Kabul, Afghanistan. Julian E. Barnes contributed reporting from Washington.

Did you miss our previous article...

https://trendinginthenews.com/usa-politics/they-seemed-like-democratic-activists-they-were-secretly-conservative-spies