WASHINGTON — The early political and economic debate over President Biden’s $2 trillion American Jobs Plan is being dominated by a philosophical question: What does infrastructure really mean?

Does it encompass the traditional idea of fixing roads, building bridges and financing other tangible projects? Or, in an evolving economy, does it expand to include initiatives like investing in broadband, electric car charging stations and care for older and disabled Americans?

That is the debate shaping up as Republicans attack Mr. Biden’s plan with pie charts and scathing quotes, saying that it allocates only a small fraction of money on “real” infrastructure and that spending to address issues like home care, electric vehicles and even water pipes should not count.

“Even if you stretch the definition of infrastructure some, it’s about 30 percent of the $2.25 trillion they’re talking about spending,” Senator Roy Blunt, Republican of Missouri, said on “Fox News Sunday.”

“When people think about infrastructure, they’re thinking about roads, bridges, ports and airports,” he added on ABC’s “This Week.”

Mr. Biden pushed back on Monday, saying that after years of calling for infrastructure spending that included power lines, internet cables and other programs beyond transportation, Republicans had narrowed their definition to exclude key components of his plan.

“It’s kind of interesting that when the Republicans put forward an infrastructure plan, they thought everything from broadband to dealing with other things” qualified, the president told reporters on Monday. “Their definition of infrastructure has changed.”

Mr. Biden defended his proposed $2 trillion package, saying it broadly qualified as infrastructure and included goals such as making sure schoolchildren are drinking clean water, building high-speed rail lines and making federal buildings more energy efficient.

Behind the political fight is a deep, nuanced and evolving economic literature on the subject. It boils down to this: The economy has changed, and so has the definition of infrastructure.

Economists largely agree that infrastructure now means more than just roads and bridges and extends to the building blocks of a modern, high-tech service economy — broadband, for example.

But even some economists who have carefully studied that shift say the Biden plan stretches the limits of what counts.

Edward Glaeser, an economist at Harvard University, is working on a project on infrastructure for the National Bureau of Economic Research that receives funding from the Transportation Department. He said that several provisions in Mr. Biden’s bill might or might not have merit but did not fall into a conventional definition of infrastructure, such as improving the nation’s affordable housing stock and expanding access to care for older and disabled Americans.

“It does a bit of violence to the English language, doesn’t it?” Mr. Glaeser said.

“Infrastructure is something the president has decided is a centrist American thing,” he said, so the administration took a range of priorities and grouped them under that “big tent.”

Proponents of considering the bulk of Mr. Biden’s proposals — including roads, bridges, broadband access, support for home health aides and even efforts to bolster labor unions — argue that in the 21st century, anything that helps people work and lead productive or fulfilling lives counts as infrastructure. That includes investments in people, like the creation of high-paying union jobs or raising wages for a home health work force that is dominated by women of color.

“I couldn’t be going to work if I had to take care of my parents,” said Cecilia Rouse, the chair of the White House Council of Economic Advisers. “How is that not infrastructure?”

But those who say that definition is too expansive tend to focus on the potential payback of a given project: Is the proposed spending actually headed toward a publicly available and productivity-enabling investment?

“Much of what it is in the American Jobs Act is really social spending, not productivity-enhancing infrastructure of any kind,” R. Glenn Hubbard, an economics professor at Columbia Business School and a longtime Republican adviser, said in an email.

Specifically, he pointed to spending on home care workers and provisions that help unions as policies that were not focused on bolstering the economy’s potential.

Senator Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, the Republican leader, has called the Biden plan a “Trojan horse. It’s called infrastructure. But inside the Trojan horse is going to be more borrowed money and massive tax increases.”

Republicans have slammed the provisions related to the care economy and electric vehicle charging options, and they have blasted policies that they have at times classified themselves as infrastructure.

Take broadband, something that conservative lawmakers have in the past clearly counted as infrastructure. Senator Roger Wicker, Republican of Mississippi, has said that the White House’s broadband proposal could lead to duplication and overbuilding. While Mr. Blunt has allowed it to count as infrastructure in a case where you “stretch the definition,” top Republicans mostly leave it out when describing how much of Mr. Biden’s proposal would go to infrastructure investment, focusing instead on roads and bridges.

Likewise, Senator Rob Portman, Republican of Ohio, said the proposal “redefines infrastructure” to include things like work force development. But one of Mr. Portman’s own proposals said that skills training was essential to successful infrastructure investment.

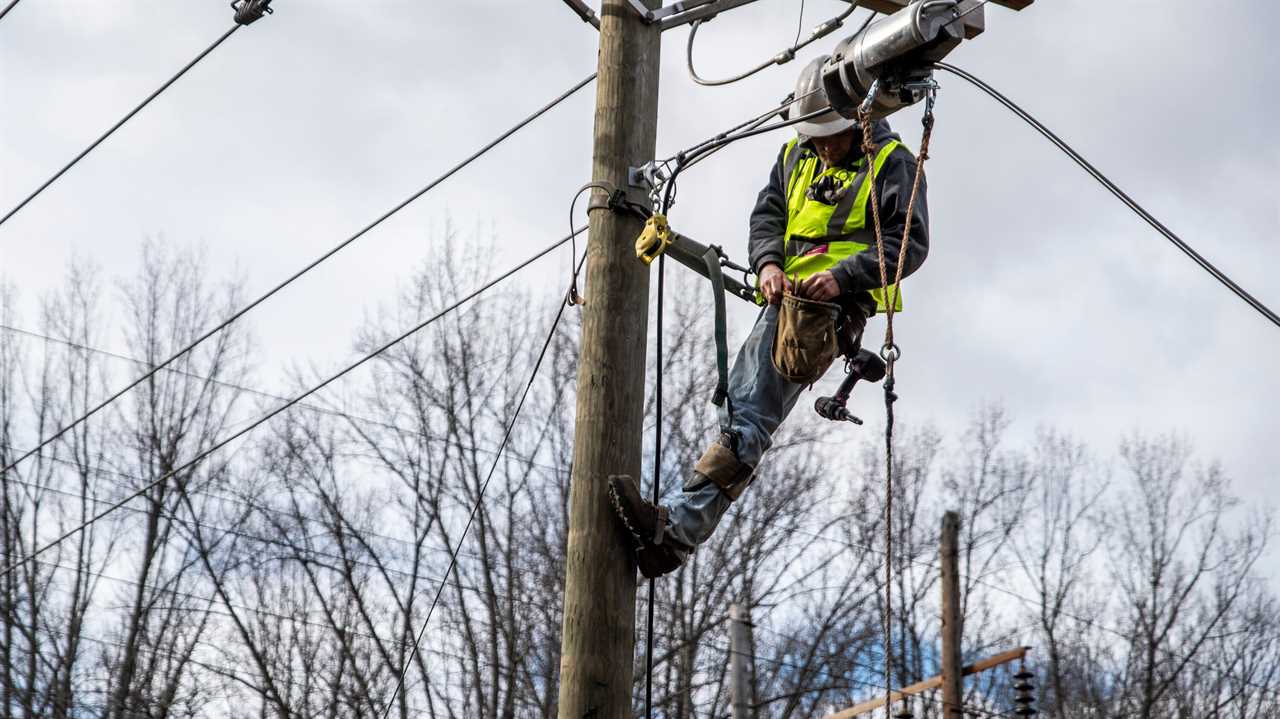

“Many people in the states would be surprised to hear that broadband for rural areas no longer counts,” said Anita Dunn, a senior adviser to Mr. Biden in the White House. “We think that the people in Jackson, Miss., might be surprised to hear that fixing that water system doesn’t count as infrastructure. We think the people of Texas might disagree with the idea that the electric grid isn’t infrastructure that needs to be built with resilience for the 21st century.”

White House officials said that much of Mr. Biden’s plan reflected the reality that infrastructure had taken on a broader meaning as the nature of work changes, focusing less on factories and shipping goods and more on creating and selling services.

Other economists back the idea that the definition has changed.

Dan Sichel, an economics professor at Wellesley College and a former Federal Reserve research official, said it could be helpful to think of what comprises infrastructure as a series of concentric circles: a basic inner band made up of roads and bridges, a larger social ring of schools and hospitals, then a digital layer including things like cloud computing. There could also be an intangible layer, like open-source software or weather data.

“It is definitely an amorphous concept,” he said, but basically “we mean key economic assets that support and enable economic activity.”

The economy has evolved since the 1950s: Manufacturers used to employ about a third of the work force but now count for just 8.5 percent of jobs in the United States. Because the economy has changed, it is important that our definitions are updated, Mr. Sichel said.

The debate over the meaning of infrastructure is not new. In the days of the New Deal-era Tennessee Valley Authority, academics and policymakers sparred over whether universal access to electricity was necessary public infrastructure, said Shane M. Greenstein, an economist at Harvard Business School whose recent research focuses on broadband.

“Washington has an attention span of several weeks, and this debate is a century old,” he said. These days, he added, it is about digital access instead of clean water and power.

Some progressive economists are pressing the administration to widen the definition even further — and to spend more to rebuild it.

“The conversation has moved a lot in recent years. We’re now talking about issues like a care infrastructure. That’s huge,” said Rakeen Mabud, the managing director of policy and research at the Groundwork Collaborative, a progressive advocacy group in Washington. But “there’s room to do more,” she said. “We should take that opportunity to really show the value of big investments.”

Some economists who define infrastructure more narrowly said that just because policies were not considered infrastructure did not mean they were not worth pursuing. Still, Mr. Glaeser of Harvard cautioned that the bill’s many proposals should be evaluated on their merits.

“It’s very hard to do this much infrastructure spending at this scale quickly and wisely,” he said. “If anything, I wish it were more closely tied to cost-benefit analysis.”

Did you miss our previous article...

https://trendinginthenews.com/usa-politics/asa-hutchinson-gop-governor-of-arkansas-vetoes-antitransgender-bill