Ever since the Affordable Care Act became law in 2010 — a big deal, in the (sanitized) words of Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr. — Democrats have itched to fix its flaws.

But Republicans united against the law and, for the next decade, blocked nearly all efforts to buttress it or to make the kinds of technical corrections that are common in the years after a major piece of legislation.

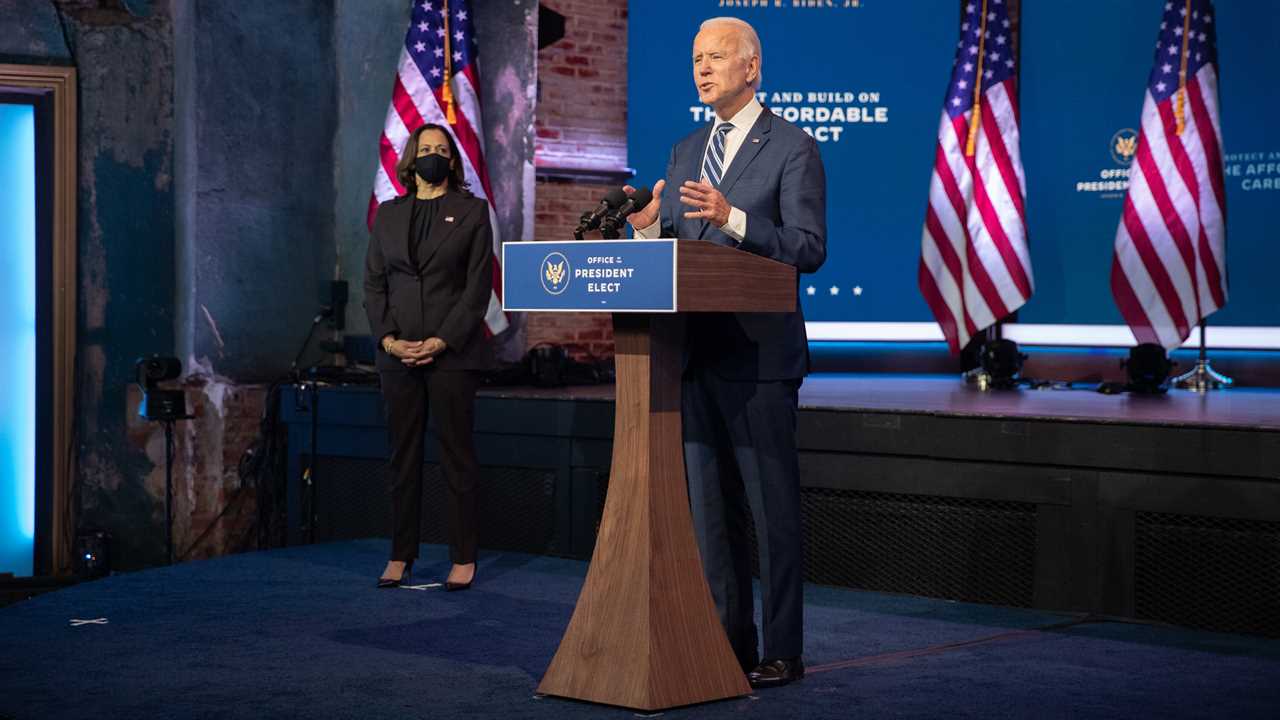

Now the Biden administration and a Democratic Congress hope to engineer the first major repair job and expansion of the Affordable Care Act since its passage. They plan to refashion regulations and spend billions through the stimulus bill to make Obamacare simpler, more generous and closer to what many of its architects wanted in the first place.

“This is the biggest expansion that we’ve had since the A.C.A. was passed,” said Representative Frank Pallone of New Jersey, who helped draft the health law more than a decade ago and leads the House Energy and Commerce Committee. “It was envisioned that we’d do this periodically, but we didn’t think we’d have to wait so long.”

The Affordable Care Act has expanded coverage to more than 20 million Americans, cutting the uninsured rate to 10.9 percent in 2019 from 17.8 percent in 2010. It did so by expanding Medicaid to cover those with low incomes, and by subsidizing private insurance for people with higher earnings. But some families still find the coverage too expensive and its deductibles too high, particularly those who earn too much to qualify for help.

Tucked inside the stimulus bill that the House passed early on Saturday are a series of provisions to make the private plans more affordable, at least in the short term.

The legislation, largely modeled after a bill passed in the House last year, would make upper-middle-income Americans newly eligible for financial help to buy plans on the Obamacare marketplaces, and would increase the subsidies already going to lower-income enrollees. The changes would last two years, cover 1.3 million more Americans and cost about $34 billion, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

For certain Americans, the difference in premium prices would be substantial: The Congressional Budget Office estimates that a 64-year-old earning $58,000 would see monthly payments decline from $1,075 under current law to $412 with the new subsidies.

It was a blow to Obamacare’s authors when the Supreme Court allowed states to refuse to expand Medicaid, the health law’s primary tool for bringing comprehensive coverage to poor Americans. Multiple states have joined the expansion in recent years, some via ballot initiative, but some Republican governors have steadfastly rejected the program, resulting in two million uninsured Americans across 12 states.

The stimulus package aims to patch that hole by increasing financial incentives for states to join the program. Though Democrats are offering holdout states larger payments than they’ve contemplated in the past, it’s unclear whether it will be enough to lure state governments that have already left billions on the table. Under current law, the federal government covers 90 percent of new enrollees’ costs.

Republican critics of the law contend that Democrats are seeking to install long-sought permanent policies through a temporary stimulus plan.

“Suffice it to say, this is not Covid relief,” said Senator Bill Cassidy of Louisiana, who helped write a prominent Obamacare repeal bill in 2017. “It’s fulfilling the agenda of the Biden administration under the guise of Covid relief.”

Mr. Cassidy fears that short-term spending increases on Obamacare will prove difficult to undo. He cited a quotation from former President Ronald Reagan: “Nothing lasts longer than a temporary government program.”

The White House and the Department of Health and Human Services (H.H.S.) have already begun to advertise insurance options and make them easier to get. On Feb. 15, the Biden administration opened a special enrollment period so that uninsured people could sign up for coverage right away, making a major effort to publicize the opportunity. Officials have also begun rolling back Trump-era work requirements in the Medicaid program.

Other regulatory changes are also planned. Xavier Becerra, Mr. Biden’s choice to lead H.H.S., testified about his ambitions on Capitol Hill this week. Officials are hoping to resolve the “family glitch” problem, which makes Obamacare insurance expensive for the children or spouses of workers who get insurance only for themselves at their job. Officials plan to tighten the rules for private short-term insurance plans that are not required to cover a full set of benefits. And they are considering a long list of technical changes aimed at making plans more comprehensive.

“Any one of these changes individually is moderate, but stack one on top of another and you get a big boost to the Affordable Care Act,” said Jonathan Cohn, author of “The Ten Year War,” a new history of the health law. “It doesn’t change the law’s structure, but it does make it much more generous.”

Those close to the effort say its ambitions — and its limits — reflect the preferences of those leading the way. Mr. Biden, who was involved in the passage and rollout of Obamacare as vice president, ran on the idea of expansion, not upheaval. And leaders in Congress who wrote Obamacare have been watching it in the wild for a decade, slowly developing legislation to address what they see as its gaps and shortcomings. Many see their work as a continuing, gradual process, in which lawmakers should make adjustments, assess their effects, and adjust again.

“When you think about where we thought the A.C.A. was headed four years ago, and contrast that to where we are right now, on the cusp of a massive expansion of affordability, it’s pretty exciting,” said Christen Linke Young, deputy director of the White House Domestic Policy Council for Health and Veterans Affairs.

But Bob Kocher, an economic adviser in the Obama administration who is now a partner at the venture capital firm Venrock, said that beyond the current changes, Mr. Biden’s mission on Obamacare seemed more modest, more like “don’t break it.”

“I don’t think he has any ambition in mind beyond managing it,” he said.

To aid in the effort, President Biden has recruited a host of former Obama administration aides. His picks for top jobs at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the Office of Management and Budget, as well as key deputies at H.H.S., all worked on the first rounds of Obamacare policymaking. Many key congressional aides working on health care now also helped write the Affordable Care Act.

Born in the Great Recession, the Affordable Care Act was drafted with a focus on costs. Political compromises and concerns about runaway deficits kept the law’s overall 10-year price tag under $1 trillion, and included enough spending cuts and tax increases to pay for it. Those constraints led its architects to scale back the financial help for Americans buying their own coverage. Staffers who wrote the formulas said they ran hundreds of simulations to figure out how to cover the most people within their budget.

Those who wrote the regulations that interpreted the law also recall drafting rules that erred on the side of spending less to avoid blowback or litigation.

Republicans, who spent a decade dead set on repealing the law, blocked any policies to expand its reach. And the fiscal politics of the Obama years would have foreclosed the kind of subsidy expansion under discussion now, even if the law had been less politically divisive.

Now, with Democrats back in control of Congress and the White House, there is new enthusiasm for expanding health coverage. Against the background of the pandemic and changing views about federal debt among many economists, lawmakers are less concerned about deficit spending than they used to be.

But the Biden health project still faces challenges, and it may disappoint his allies. The new proposed spending, which would bring the law’s subsidies in line with early drafts of the Affordable Care Act, is temporary. Making those changes permanent could cost hundreds of billions over a decade, a sum that may spook moderate Democrats once the economy is in better health.

And for many Democrats, the overhauls do not go as far they had hoped. Mr. Biden ran not only on subsidy expansions and technical fixes, but also on a lowering of the Medicare eligibility age and the creation of a so called public-option plan, government insurance that people could choose in place of private coverage. Members of Congress have introduced Medicare expansion and public-option bills, but neither type of proposal appears likely to move soon.

Mr. Becerra has previously supported a single-payer system. He faced questions about his commitment to that idea from Senator Bernie Sanders, who has repeatedly introduced Medicare for All legislation, and from Republican senators who oppose the idea. In each case, he responded similarly: The Affordable Care Act is the president’s focus, and his own as well.

“I’m here at the pleasure of the president of the United States,” Mr. Becerra said. “He’s very clear where he is — he wants to build on the A.C.A. That will be my mission.”

Pramila Jayapal, a Democratic congresswoman from Washington State, who led a joint Biden-Sanders policy task force during Mr. Biden’s presidential campaign, says she is heartened by the measures the administration is taking — but concerned that the current efforts don’t yet match the promises made to progressives during the campaign. She said she would keep pushing for more generous health plans and an expansion of Medicare to cover more Americans, among other measures.

“I believe we’re going to do so many things in this package, and I do think it’s a good package,” she said. “But I believe we haven’t done enough to help everyone who has fallen into the cracks.”