Earlier this year Mighty Well, an adaptive clothing company that makes fashionable gear for people with disabilities, did something many newish brands do: It tried to place an ad for one of its most popular products on Facebook.

The product in question was a gray zip-up hoodie ($39.95) with the message: “I am immunocompromised — Please give me space.” The “immunocompromised” was in a white rectangle, kind of like Supreme’s red one. It has rave customer reviews on the company’s website

Facebook — or rather, Facebook’s automated advertising center — did not like the ad quite so much.

It was rejected for violating policy — specifically, the promotion of “medical and health care products and services including medical devices,” though it included no such products. Mighty Well appealed the decision, and after some delay, the ruling changed.

This may not seem like such a big deal. After all, the story ended well.

But Mighty Well’s experience is simply one example of a pattern that has been going on for at least two years: The algorithms that are the gatekeepers to the commercial side of Facebook (as well as Instagram, which is owned by Facebook) routinely misidentify adaptive fashion products and block them from their platforms.

At least six other small adaptive clothing companies have experienced the same problems as Mighty Well, which was founded four years ago by Emily Levy and Maria Del Mar Gomez — some to an even greater extent. One brand has been dealing with the issue on a weekly basis; another has had hundreds of products rejected. In each instance, the company has had to appeal each case on an item-by-item basis.

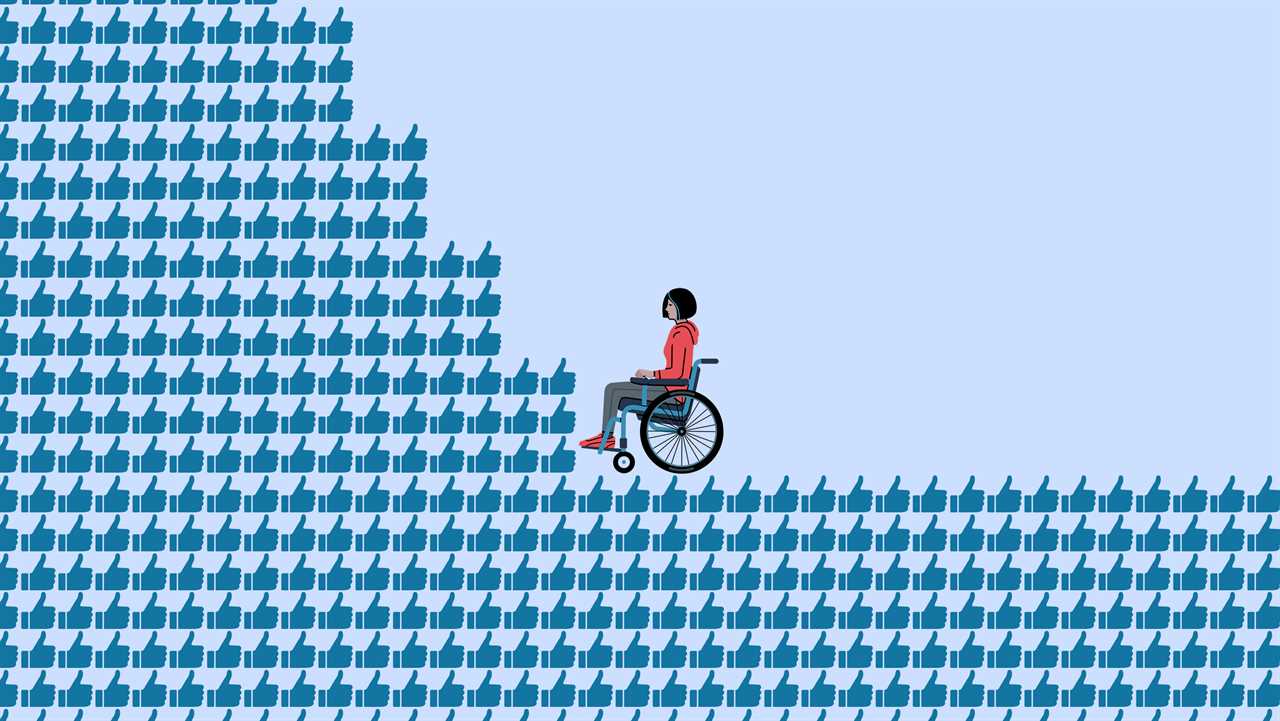

At a time when the importance of representation is at the center of the cultural conversation, when companies everywhere are publicly trumpeting their commitment to “diversity, equity, and inclusion” (D.E.I.) and systemic change, and when a technology company like Facebook is under extra deep scrutiny for the way its policies can shape society at large, the adaptive fashion struggle reflects a bigger issue: the implicit biases embedded in machine learning, and the way they impact marginalized communities.

“It’s the untold story of the consequences of classification in machine learning,” said Kate Crawford, the author of the coming book “Atlas of AI” and the visiting chair in A.I. and justice of the École Normale Supérieure in Paris. “Every classification system in machine learning contains a worldview. Every single one.”

And this one, she said, suggests that “the standard human” — one who may be interested in using fashion and style as a form of self-expression — is not automatically recognized as possibly being a disabled human.

“We want to help adaptive fashion brands find and connect with customers on Facebook,” a Facebook spokeswoman emailed when contacted about the issue. “Several of the listings raised to us should not have been flagged by our systems and have now been restored. We apologize for this mistake and are working to improve our systems so that brands don’t run into these issues in the future.”

Facebook is not alone in having A.I.-erected barriers to entry for the adaptive fashion businesses. TikTok and Amazon are among the companies that have had similar issues. But because of Facebook’s 2.8 billion users and because of its stance as the platform that stands for communities, Facebook, which recently took out ads in newspapers, including this one as well as The Washington Post and The Wall Street Journal, saying they were “standing up” for small businesses, is particularly important to disabled groups and the companies that serve them. And Instagram is the fashion world’s platform of choice.

Of Clothes and Context

Adaptive fashion is a relatively new niche of the fashion world, though one that is growing quickly. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1 in 4 adults in the United States is living with a disability, and Coherent Market Insights has projected that the global adaptive clothing market will be worth more than $392 billion by 2026.

There are now brands that create covers for catheter lines that look like athletic sleeves; colostomy and ostomy bag covers in vivid colors and patterns; underwear that attaches via side closures rather than having to be pulled on over the legs; chic jeans and pants tailored to accommodate the seated body with nonirritating seams; and button-up shirts that employ magnetic closures instead of buttons. These and many other designs were created to focus on the individual, not the diagnosis.

There are some big companies and retailers working in the space, including Tommy Hilfiger, Nike and Aerie, but many of the brands serving the community are small independents, most often started by individuals with personal experience of disability and focused on direct-to-consumer sales. Often they include designers and models with disabilities, who also appear in their advertisements and storefronts.

Maura Horton is one of the pioneers of adaptive clothing. In 2014, she created MagnaReady, a system of magnetic buttons, after her husband learned he had Parkinson’s. In 2019, she sold her company to Global Brands Group, the fashion behemoth that owns Sean John and Frye. Last year Ms. Horton and GBG created JUNIPERunltd, a content hub, e-commerce platform and community focused on the disabled sector, as well as Yarrow, their own proprietary adaptive fashion brand. Ms. Horton planned to advertise on both Facebook and Instagram.

Between November and January, she submitted four series of ads that included a pair of Yarrow trousers, one designed with a “standing fit,” and featuring a woman … well, standing up, and one designed for a person who is seated and featuring a young woman using a wheelchair (the cut changes depending on body positioning). Each time, the standing ad was approved and the wheelchair ad was rejected for not complying with commerce policies that state: “Listings may not promote medical and health care products and services, including medical devices, or smoking cessation products containing nicotine.”In the “seated fit,” the system apparently focused on the wheelchair, not the product being worn by the person in the wheelchair. But even after Ms. Horton successfully appealed the first rejection, the same thing happened again. And again. Each time it took about 10 days for the system to acknowledge it had made a mistake.

“Automation,” Ms. Horton said, “can’t really do D.E.I.”

The problem, Ms. Crawford said, is context. “What does not do context well? Machine learning. Large-scale classification is often simplistic and highly normalized. It is very bad at detecting nuance. So you have this dynamic human context, which is always in flux, coming up against the gigantic wall of hard coded classification.”

Not one of the adaptive fashion companies spoken to for this article believes the platform is purposefully discriminating against people with disabilities. Facebook has been instrumental in creating alt text so that users with impaired vision can access the platform’s imagery. The company has named disability inclusion as “one of our top priorities.” And yet this particular form of discrimination by neglect, first called out publicly in 2018, has apparently not yet risen to the level of human recognition.

Instead, machine learning is playing an ever larger role in perpetuating the problem. According to the Facebook spokeswoman, its automated intelligence doesn’t just control the entry point to the ad and store products. It largely controls the appeal process, too.

The Latest in a History of Misunderstandings

Here’s how it works: A company makes an ad, or creates a shop, and submits it to Facebook for approval, an automated process. (If it’s a storefront, the products can also arrive via a feed, and each one must comply with Facebook rules.) If the system flags a potential violation, the ad or product is sent back to the company as noncompliant. But the precise word or part of the image that created the problem is not identified, meaning it is up to the company to effectively guess where the problem lies.

The company can then either appeal the ad/listing as is, or make a change to the image or wording it hopes will pass the Facebook rules. Either way, the communication is sent back through the automated system, where it may be reviewed by another automated system, or an actual person.

According to Facebook, it has added thousands of reviewers over the last few years, but three million businesses advertise on Facebook, the majority of which are small businesses. The Facebook spokeswoman did not identify what would trigger an appeal being elevated to a human reviewer, or if there was a codified process by which that would happen. Often, the small business owners feel caught in an endless machine-ruled loop.

“The problem we keep coming up against is channels of communication,” said Sinéad Burke, an inclusivity activist who consults with numerous brands and platforms, including Juniper. “Access needs to mean more than just digital access. And we have to understand who is in the room when these systems are created.”

The Facebook spokeswoman said there were employees with disabilities throughout the company, including at the executive level, and that there was an Accessibility team that worked across Facebook to embed accessibility into the product development process. But though there is no question the rules governing ad and store policy created by Facebook were designed in part to protect their communities from false medical claims and fake products, those rules are also, if inadvertently, blocking some of those very same communities from accessing products created for them.

“This is one of the most typical problems we see,” said Tobias Matzner, a professor of media, algorithms and society at Paderborn University in Germany. “Algorithms solve the problem of efficiency at grand scale” — by detecting patterns and making assumptions — “but in doing that one thing, they do all sorts of other things, too, like hurting small businesses.”

Indeed, this is simply the latest in a long history of digital platform problems in reconciling the broad stroke assumptions demanded by code with complex human situations, said Jillian C. York, the director for international freedom of expression at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a nonprofit focused on digital rights. Other examples include Facebook’s past controversies over banning breastfeeding pictures as sexual, and Instagram’s 2015 banning of photos by the poet Rupi Kaur that explored menstruation taboos. Both issues were later corrected after a public outcry. The difference now is that rather than personal content and free speech, the issue has become one of commercial speech.

“We’ve often talked about this in terms of user content, and Facebook has been pushed to take into account cultural differences,” said Tarleton Gillespie, the author of “Custodians of the Internet.” “But clearly the ability to engage in commerce is crucial for a community, and I don’t think they have been pushed as far in that area.”

Make Noise or Give Up

It was on Dec. 3, 2018, when Helya Mohammadian, the founder of Slick Chicks, a company that creates adaptive underwear that is sold by companies like Nordstrom and Zappos, first noticed the problem. Links to its website posted on Facebook and Instagram sent users to an error page and this statement: “The link you tried to visit goes against the Facebook community standards,” a practice known as “shadow banning.”

The images on the site featured brand ambassadors and customers modeling the product, though not in a provocative way. Still, the algorithm appeared to have defaulted to the assumption that it was looking at adult content.

Ms. Mohammadian began appealing the ruling via the customer support service, sending roughly an email a day for three weeks. “We probably sent about 30,” she said. Finally, in mid-December, she got fed up and started a petition on change.org titled “Make Social Media More Inclusive.” She quickly received about 800 signatures and the bans were lifted.

It could have been a coincidence; Facebook never explicitly acknowledged the petition. But her products were not flagged again until March 2020, when a photo of a woman in a wheelchair demonstrating how a bra worked was rejected for violating the “adult content” policy.

Care + Wear, an adaptive company founded in 2014 that creates “healthwear” — port access shirts and line covers, among other products — spent years being frustrated by the irrational nature of the automated judgment process. One size of a shirt would be rejected by Facebook while the very same shirt in another size was accepted as part of its shop feed. Finally, in March of last year, the company resorted to hiring an outside media buying agency in part because it could actually get a Facebook person on the phone.

“But if you are a small company and can’t afford that, it’s impossible,” said Jim Lahren, the head of marketing.

Abilitee Adaptive, which was founded in 2015 and until late last year made insulin pump belts and ostomy bag covers in bright, eye-catching colors, started advertising their products on Facebook in early 2020; about half of those it submitted were rejected. The company tried changing the language in the ads — it would resubmit some products five times, with different wording — but some bags would be approved and others not.

“The response was very vague, which has been frustrating,” said Marta Elena Cortez-Neavel, one of the founders of Abilitee. In the end, the company stopped trying to advertise on Facebook and Instagram. (Subsequently, the founders split up, and Abilitee is being reorganized.)

Ms. Del Mar Gomez of Mighty Well said she’d had similar problems with language, and on occasion she had to remove so many key words and hashtags from an ad that essentially it became impossible to find. Lucy Jones, the founder of FFora, a company that sells wheelchair accessories like cups and bags, found its products blocked for being “medical equipment.” (“I thought of them more like stroller cups,” she said.) Like Ms. Cortez-Neavel of Abilitee, she simply gave up because she felt that, as a small business, her resources were better used elsewhere.

Alexandra Herold, the founder and sole full-time employee of Patti + Ricky, an online marketplace, said that of approximately 1,000 adaptive fashion products by the 100 designers that it hosts (and wanted to offer on its Facebook store), at least 200 have been mistaken for medical equipment, flagged for “policy violations” and caught up in the appeals process. She is exhausted by the constant attempts to reason with the void of an algorithm.

“How can we educate the world that adaptive clothes” — not to mention the people who wear them — “are a fundamental part of fashion, when I am having to constantly petition to get them seen?” she asked.