It was already late on Nov. 9 when Eric Coomer, then the director of product strategy and security for Dominion Voting Systems, left his temporary office on Daley Plaza in Chicago and headed back to the hotel where he’d been staying for the previous few weeks. Both the plaza and the hotel had the eerie post-apocalyptic feel of urban life during the pandemic, compounding the sense of disorientation and apprehension he felt as he made his way up to his room.

Earlier that evening, a colleague sent him a link to a video of Coomer speaking at a conference with a menacing comment below it. “Hi Eric! We know what you did,” the commenter wrote. That link eventually led Coomer to a second video, which he watched in his hotel room. What he saw, he quickly realized, was something that was likely to wreck his life, hurt his employer and possibly erode trust in the electoral process.

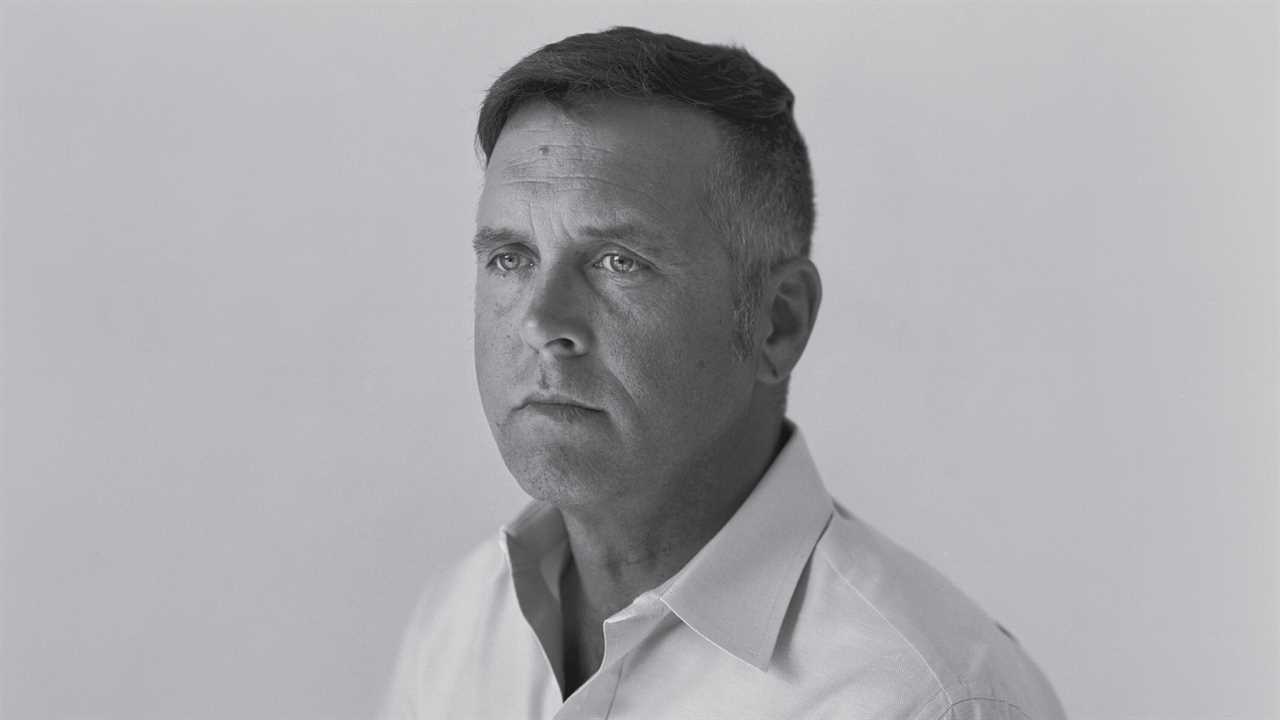

Over the past decade, Coomer, 51, has helped make Dominion one of the largest providers of voting machines and software in the United States. He was a gifted programmer, known to be serious about his work but informal about almost everything else — prone to profanities, with a sense of humor that could have blunt force. Coomer, who traveled around the world for competitive endurance bike races, would have blended in on the campus of Google, just one in a crowd of nonconformist tech types. In the more corporate business of elections, he stood out for the full-sleeve tattoos on his arms (one of Francis Bacon’s “Screaming Popes,” some Picasso bulls) and the half-inch holes in his ears where he once wore what are known as plugs.

Coomer was accustomed to working long days during the postelection certification process, but the stress that November was building quickly. Donald Trump was demanding recounts. The president’s allies in the Stop the Steal movement had spent months stoking fears of election fraud. And then on Sunday, Nov. 8, Sidney Powell, a lawyer representing the Trump campaign, appeared on Fox News and claimed, without evidence, that Dominion had an algorithm that switched votes from Trump to Biden.

The video Coomer watched in his hotel room represented a new development in Dominion’s troubles. It was that day’s episode of “The Conservative Daily Podcast,” a program previously unknown to Coomer, which had been posted to YouTube. “We’re going to expose someone inside of Dominion Voting Systems, specifically related to antifa, and related to someone that is so far left, and is controlling elections and his fingerprints are in every state,” said the show’s co-host, a man using the pseudonym Joe Otto. Otto — who would eventually reveal himself to be Joe Oltmann, a Colorado entrepreneur — claimed that he had found a smoking gun that proved fraud at Dominion: “We 100 percent know that the election was rigged.”

About 11 minutes in, Coomer heard Oltmann say his name. “The conversation will be about a man named Eric Coomer,” Oltmann said, spelling it out: “C-O-O-M-E-R.” Next Coomer was staring at a photo of himself up on the screen in what Oltmann called “his little outfit,” a bike uniform Coomer wore in 2016 for a six-day endurance mountain-biking race. Coomer was looking at his own half-smirk, half-smile, the face of a middle-aged man with a sparse goatee, staring into the glare in sunglasses. What other photos did Oltmann have? What other artifacts of his life, of his family — and how hard was this man looking for all of it?

Oltmann claimed that, earlier that year, he had infiltrated what he said was an antifa phone call and overheard someone — someone he claimed had been identified as Eric at Dominion — assure his supposed fellow antifa members that Trump would lose. “He responds — and I’m paraphrasing this, right? — ‘Don’t worry about the election, Trump is not going to win. I made effing sure of that,’” Oltmann said. He told his listeners that he thought little of who this Eric at Dominion might be until after the election, when a friend sent him a Facebook post about election troubles that mentioned Eric Coomer’s name. Suddenly, Oltmann said, his interest was reawakened. He started looking into Coomer, he said, and “the more information I got, the scarier it got.”

Coomer had given conspiracy theorists a valuable resource, a grain of sand they could transform into something that had the feel — the false promise — of proof.

Oltmann said that in his research he found that Coomer had written “vile” anti-Trump Facebook posts. Oltmann proceeded to read from one of those posts, from July 2016, which characterized Donald Trump as “autocratic,” “narcissistic” and a “fascist,” among other, more vulgar insults. “I don’t give a damn if you’re friend, family or random acquaintance,” Oltmann read. Anyone who decided to “pull the lever, mark an oval, touch the screen for that carnival barker ... UNFRIEND ME NOW.” Oltmann displayed a screenshot of the post, which said that the author’s opinions “are not necessarily the thoughts of my employer, though if not, I should probably find another job. Who wants to work for complete morons?” Oltmann’s co-host, Max McGuire, also read from an anonymous open letter that explained that, while there was no formal organization known as “antifa,” the ideas the public associates with it are worth supporting. “There’s no such thing as being antifascist; either you are a decent human being with a conscience, or you are a fascist,” McGuire read. The letter, Oltmann said, had appeared on Coomer’s Facebook.

Coomer watched the video in shock. He is adamant that he never participated in any antifa phone call, and he felt disgusted by the accusation that he had done anything to change the results of the election. The Trump campaign and its allies have introduced more than 60 lawsuits claiming election fraud in this country, but no court has found persuasive evidence to support the idea that Coomer, Dominion or anyone else involved in vote-counting changed the election results. Bipartisan audits of paper ballots in closely contested states such as Georgia and Arizona confirmed Biden’s victory; and prominent Republicans, including Attorney General Bill Barr and Trump’s official in charge of election cybersecurity, have reaffirmed the basic facts of the election: Over all, the results were accurate, the election process was secure and no widespread fraud capable of changing the outcome has been uncovered.

Oltmann is now the subject of a defamation suit brought by Coomer. It currently names, as co-defendants, 14 parties responsible for the dissemination of Oltmann’s claims about that alleged antifa phone call, including Sidney Powell, Rudy Giuliani and the Trump campaign. (Dominion has filed separate defamation suits against Giuliani, Powell, Fox News and others. Lawyers for Giuliani, Powell and for the Trump campaign declined to comment. Fox called the Dominion litigation “baseless” and defended its right to tell “both sides” of the story.) Oltmann’s best defense would be to provide corroboration of his claims about that phone call — he has said there were as many as 19 people on the line — but he has so far declined to do so.

As Coomer watched the video, though, he felt a second strong emotion: a powerful sense of regret — because the Facebook posts were, in fact, authentic. Why, he thought, hadn’t he just deleted them? Coomer could imagine how his words would sound to just about any Republican, let alone someone already hearing on Fox News that Dominion was switching votes for Biden. He told me that he believed every word of what he said on Facebook, but when colleagues later asked him what he was thinking, he was frank: He had screwed up. At a time when well-funded efforts to sow mistrust in the election were already underway, Coomer had given conspiracy theorists a valuable resource, a grain of sand they could transform into something that had the feel — the false promise — of proof.

Elections in the United States are impossibly convoluted. Every county — and, in some states, every municipality — runs its own election, creating a patchwork system in which voters in one place may have a remarkably different voting process from their neighbors just a few miles away. That variation can breed mistrust: If voters in one county believe their election process is being administered correctly, different methods in other counties might strike them as suspect.

Local governments also rely on private companies like Dominion and its competitors ES&S and Hart InterCivic, which together control 90 percent of the voting-machine market, to provide machines, software and technical support. For Americans who are suspicious about an election result — or are looking to create suspicions — these relatively obscure, private companies present an obvious target. In 2004, after George W. Bush narrowly won the presidency, Democrats focused on possible irregularities in Ohio, whose 20 electoral votes would have given the presidency to John Kerry. The voting machines used in Ohio that year came from Diebold, whose chief executive, Walden O’Dell, was a longtime Republican donor. A year before the election, O’Dell wrote a letter to about 100 people inviting them to a fund-raiser: “I am committed to helping Ohio deliver its electoral votes to the president next year,” he wrote. The language reinforced mistrust of Diebold machines among some Democrats. O’Dell later said the letter was a “huge mistake,” and Diebold ultimately sold its voting-machine business.

Dominion was founded in the wake of a different controversy: the failure of punch-card voting machines — and their infamous hanging chads — in the 2000 election. After Congress funded a bill to replace those machines, many counties purchased direct-recording electronic (D.R.E.) voting machines, which eliminated paper ballots altogether. The limits of that approach became apparent in 2006, when, in Sarasota, Fla., a Congressional race that used D.R.E. machines made by ES&S produced a result that struck partisans and neutral observers as unlikely. ES&S stood by the results, but in the absence of a paper ballot, doubts and uncertainty lingered.

Dominion was well-positioned at that moment. John Poulos, the company’s chief executive and one of its founders, started the business in 2003, serving a small circle of clients who favored a paper ballot. Additionally, Dominion developed a tabulator that kept a digital image of the paper ballots so they could be easily audited. (They also sold machines that met the needs of visually impaired voters, with audio interfaces and headphones that allowed for independence and anonymity.)

Dominion grew fast, acquiring the assets of a competitor, Sequoia Voting Systems, in 2010. Among Sequoia’s staff was Eric Coomer, who became Dominion’s vice president of engineering for the United States. Coomer worked with Poulos for more than a decade at Dominion. (The investment firm Staple Street Capital owns a majority share in the company.) Coomer’s role shifted over time from overseeing the company’s engineers to a more strategic role, working directly with election officials in various states and discussing Dominion’s services on technical panels.

For the 2020 election, activists and experts pushed for paper ballots nationwide, to offer a straightforward, easily audited record. Coomer, expressing a common assurance among election specialists, has pointed out that because every Dominion system “creates a durable, voter-verifiable, paper record of the cast votes, which is the official record,” voters had concrete evidence of how the vote went in the face of any allegations of electronic vote-switching or other fraud.

At the same time, voting-machine businesses knew that paper ballots can create some confusion among voters — such as the worry that ink from Sharpies and other markers could bleed through the page and invalidate their vote. In fact, ballot layouts can avoid misreads from bleed-throughs, and Sharpies have the advantage drying quickly, so ink doesn’t smudge on the scanner.

Concerns about Sharpies, however, ending up feeding into coordinated efforts to cast doubt on the 2020 election. In Maricopa County, Ariz., the most populous county in a key swing state, Dominion ballots with a Sharpie-friendly layout were used, and poll workers handed the markers out. Some voters weren’t prepared to use Sharpies after years of being told to avoid them. The confusion reached social media, where, in the hands of partisan messaging networks, the charge quickly became: Republicans were being given Sharpies in Maricopa County in an effort to invalidate their votes.

Dominion was still trying to help election officials address so-called Sharpiegate when Poulos got a call, on Nov. 4, with more bad news: in Antrim County, Michigan, ballots were updated shortly before Election Day but the system used to tabulate them was not. A series of fail-safe procedures meant to address such an error had been overlooked. As a result, preliminary returns showed Joe Biden leading in the heavily Republican county before they were corrected. To the frustration of key players in the election community, neither local officials nor Dominion immediately released a statement explaining what went wrong; the silence created an opportunity for those charging fraud to fill the vacuum with unfounded allegations.

Security experts distinguish between disinformation — straightforward lies — and malinformation, information that starts with a detail that is true but is then used or taken out of context to support a false story line. “It’s harder to fight malinformation, because of the fundamental truth being used to spread the lies,” says Matthew Masterson, who was a senior adviser for election security at the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency during the Trump Administration. Antrim County, he worried at the time, could be used as a prime source of malinformation.

It was not until Nov. 6 that Michigan election officials began explaining what happened. By then, rumors — including the false suggestion that Nancy Pelosi’s husband owned Dominion — had spread. Ronna McDaniel, chairwoman of the Republican National Committee, held a news conference asserting that “the fight is not over,” and that Antrim County made her worry that there could be similar irregularities elsewhere. The Michigan State Legislature issued a subpoena to state election officials asking for more information.

That same week, reports emerged of an Election Day glitch in Spalding County, Ga. There, Dominion machines were unable to call up voters’ ballots because of a problem with an outside vendor’s database and because procedures that would have caught the error or provided other ways of calling up the ballots were not followed. The local elections supervisor, however, told Politico that a Dominion representative had explained that the problem was the fault of an update the company made the night before the election.

Poulos was baffled: The technology did not allow for that kind of remote update, as the machines are not connected to the internet. “It would be like me saying I came into your house and updated your kitchen table without your knowing it,” Poulos said. None of his employees’ phone records reflected any such call, and Georgia election authorities reported that a log file that would have reflected an update the previous day showed none. The Republican secretary of state, Brad Raffensperger, eventually called for the ouster of the official. (She is no longer in that position.) But the incident was another story that would stick to Dominion. “Georgia Counties Using Same Software as Michigan Counties Also Encounter ‘Glitch,” ran the headline on Breitbart News on Nov. 7.

After Sidney Powell’s Nov. 8 appearance on Fox News, Dominion became a fixture in election-conspiracy theories. Originally, right-wing chatter was linking Dominion to election fraud even in cities like Pittsburgh, which the company did not serve. Over time, the focus shifted to three important swing states — Georgia, Arizona and Michigan — that used Dominion machines.

Before he left for work on Nov. 10, Coomer checked the settings on his Facebook account. Had he been careless? As he thought, his privacy settings ensured that his posts were only visible to his 300 or so Facebook friends. Coomer started deleting old posts, but he realized how foolishly he had put his faith in a notion of digital privacy. Any one of Coomer’s “friends”— and he had several whom he knew to be Trump supporters — could have taken screenshots of his posts and sent the information along to someone who could use it.

At work, Coomer felt an increasing sense of dread, but Poulos, the chief executive, seemed confident that the Oltmann story would blow over. From Poulos’s perspective, the Conservative Daily Podcast was hardly a top concern when Fox News was allowing Sidney Powell to air claims that Dominion switched votes.

Coomer’s younger brother, who requested that his name not be used out of fear for his safety, set up a dashboard to track online references to Eric Coomer. “I deleted it within two days,” he said — the material was too disturbing and overwhelming. He recalled some of what he saw: “People were essentially taking bets on how my brother’s corpse would be found and which nefarious shadow group would be behind his death. He would be executed by the state or he would be found with a falsified suicide note and two gunshots in the back of his head.” He and Eric’s older brother, Bill, deleted their social media profiles and alerted friends and associates not to answer questions about them; they directed their parents to do the same. The younger brother packed a go bag in case he had to flee his home.

Before long, hundreds of Dominion employees had their private information — address, phone numbers, names of loved ones — published on social media, and threats started pouring in to their Dominion email. Angry email messages kept arriving for Coomer as well, and hostile posts continued to appear on social media: “He’s goin’ to GITMO. No one escapes this. Pain is comin’!”

Over the next few days, as Coomer tried to focus on wrapping up the election certification in Chicago, he thought about his complicated past and wondered what else might surface. He grew up the rebellious child of a high-ranking military officer, a Vietnam veteran who fought during the Tet offensive and was awarded the Silver and Bronze Stars. Coomer, brainy and restless, received an R.O.T.C. scholarship but it was rescinded because of his asthma. As a teenager and into his 20s, he considered himself a skinhead, but he was aligned with a faction who were opposed to racism. “To me, being skin is being proud that you have a shaved — at least short — hair,” he wrote in 1991.

Coomer earned his Ph.D. in nuclear engineering from Berkeley in 1997 but grew disenchanted with academia. He started to fill more of his time with rock climbing and moved to Colorado. He summited Yosemite’s El Capitan several times and became well known enough among elite climbers that he landed a job at Planetoutdoors.com, which employed top athletes to answer customer questions. While he was there, he started writing code for the company. He continued climbing, until problems in his personal life slowed him down.

In 2004, at age 34, he wrote on a climbing message board about his struggles with heroin and cocaine and how much they had damaged his life. By then, he was on the verge of bankruptcy, had lost his marriage and had ended up in prison after being charged with several counts of driving under the influence. “Another bout of dry heaves racked my body as I lay on the cold cement floor of the jail cell,” he wrote. “Jail is no picnic under the best of circumstances — being in jail while withdrawing from heroin is absolutely the worst I can imagine.”

In 2005 he managed to stop using heroin for good. “I stayed with a friend for a week and told him to take my shoes and my wallet,” Coomer told me. Three months later, while he was still in withdrawal, he received a cold call from someone asking if he would consider doing programming work for Sequoia, the voting-machine company whose assets Dominion purchased five years later.

Soon, he was channeling the same obsessive focus he had for climbing into the voting-machine business, its obscure state laws and county regulations, its competing and complicated demands for privacy, security, access and verifiability. “I fell in love with the election business,” Coomer said. “There’s no money in it, and you only ever hear from people complaining about what went wrong. But it felt meaningful.”

In 2016, Coomer was on Facebook when he came across a few posts from a relative referring to Barack Obama as a Muslim born in Kenya. Coomer was appalled that one of his own family members was spreading disinformation, but instead of confronting his cousin directly, he poured all his disgust and disappointment into a 200-word anti-Trump screed that he posted on Facebook. “It was not intended for the general public,” Coomer said. “It was a lashing out.” Years later, after the death of George Floyd, Coomer posted links to a punk band singing “Pigs for Slaughter” and a hip-hop song called “Cop Shot.” (On his podcast, Oltmann highlighted Coomer’s linking to both songs.)

About a year before the 2020 election, Coomer was part of several conversations among Dominion employees about how to balance their right to express themselves with the sensitivities specific to their industry. Dominion also searched through its employees’ social media accounts, checking for comments or tweets that might reflect poorly on the company. No one ever raised any concerns with Coomer about his posts, because his posts were available only to his Facebook friends.

On Friday, Nov. 13, the right-wing news outlet the Gateway Pundit, picking up on Oltmann’s podcast, ran a story that mentioned Coomer by name in the headline, included links to videos in which Coomer was talking about election security, and ran a full reprint of the open letter about antifa that he had reposted on Facebook. While most of that letter was uncontroversial — “Antifa supports and defends the right of all people to live free from oppressive abuse of power” — one line concluded that while nonviolent protest was preferable, “we cannot and will not take responsibility for telling people how they are allowed to be righteously outraged.” The letter also called for President Trump and Vice President Pence to resign, although “Nancy Pelosi isn’t a great deal of improvement.” (Coomer says he considered the letter satirical.) As soon as the Gateway Pundit article ran, Coomer knew he no longer could hope, realistically, that his name would recede from the news.

Later that evening, Poulos asked Coomer to join a call with Gabriel Sterling, the chief operating officer for the Georgia secretary of state. Sterling met Coomer in 2019, when Dominion won a contract to help Georgia upgrade its voting machines. Someone had forwarded Sterling an article — possibly the one in the Gateway Pundit, he says — that featured the Facebook posts as well as Oltmann’s claim about Coomer rigging the election. “My gut told me it was crap to begin with, but I had to ask the question,” Sterling says.

Yes, Coomer told both men, I did write or repost those things; no, it has never affected my work. No, I never was on an antifa phone call. No, I never said that I would interfere in the election in any way. Sterling — who considered Coomer “one of the best” in the business — told Coomer that those postings, especially the one about antifa, were “a dumb-ass thing to do.” Coomer sounded deflated to Sterling. Coomer says it was “excruciating” to realize that Sterling’s reputation might suffer.

When they hung up the phone, Poulos made it clear that he found the situation deeply problematic. Coomer began to fear he might lose his job but became defiant. “I was like — ‘I don’t know, First Amendment?’” Coomer told me. Dominion, he reminded Poulos, had done nothing wrong; he had done nothing wrong. “My attitude was: This is bullshit. I’ve never done anything but try to make the whole process more transparent and auditable and free and fair.”

Election officials who knew Coomer were surprised that he would express his political views so bluntly. “It’s not what we do in this industry,” says Masterson, the election-security adviser in the Trump administration. “Generally, this community is very tough on people who don’t toe that line.” Masterson considered the misstep an anomaly for Coomer, someone he had known for about a decade. “He was serious about his job,” Masterson said. “I never encountered him as being anything other than professional and making the system as good as he could.”

The posts also pained Jennifer Morrell, a founder of the Elections Group, a company that helps counties and states comply with voting regulations. “It didn’t look good,” she said. “And that’s the frustrating part. I know this individual to be a really decent person who cares a lot about democracy and getting things right and transparency — and you read something like that, and it is a really hard thing to get past, for critics.” Morrell, who came to know Coomer through a Colorado working group intended to improve the state’s audit system, described him as “irreverent” but clearly ethical; the posts, she said, did not reflect the person she knew.

Coomer was hardly the first person to seek the rush of righteous self-expression on social media, only to discover the long-lasting costs later. He spent a lot of time wondering how Oltmann got his hands on those posts. Had a political operative been doing opposition research on various election officials, keeping it at the ready, depending on the election results? Coomer, a self-described motorhead with an interest in vintage cars, started to think the source might have been a Facebook friend he made at Bandimere Speedway, a racetrack he sometimes visited. The racetrack had hosted a meeting organized by a local businessman who was starting to make a name for himself in Colorado politics, Joe Oltmann.

If Eric Coomer’s life changed on Nov. 9, so did Joe Oltmann’s. On his follow-up podcast the next day, Oltmann told his audience that he had good news. “I have been in touch with someone who has put us in touch with the Trump attorneys,” he said.

That week, Oltmann spoke to Jenna Ellis, a Trump campaign lawyer who frequently appeared with Giuliani to promote lawsuits to challenge the election results. She told him that he should prepare a notarized affidavit of his allegations, which he did with help from the lawyer and conservative radio host Randy Corporon. That Saturday, Corporon invited Oltmann on his radio show, and Representative Lauren Boebert, a Republican from Colorado, called in to talk about the election. She thanked Oltmann for his work.

Before the election upended his life, Oltmann was the chief executive of PIN Business Network, a digital-marketing company that he founded, which had about 60 employees. The co-owner of a gun shop, he was politically conservative and community-minded — a member of the United Way Tocqueville Society and a board member for a nonprofit group that assists refugees. (Oltmann asked that I not name the organization, though it confirmed his association. He also rejects the label “conservative” despite the name of his podcast.) The arrival of the coronavirus pandemic marked his move into a more public role: In the spring of 2020, he helped start the Reopen Colorado movement, which organized anti-lockdown protests. People were struggling as others were “throwing the Constitution in the trash,” he told me. He began giving impassioned interviews about the public-health measures imposed by the state’s governor, Jared Polis.

By that October, following the 2020 summer of protests, he had founded a nonprofit group, FEC United, intended, its website says, “to defend the foundation of our American Way of Life through the pillars of Faith, Education and Commerce.” FEC formed a partnership with a group known as the United American Defense Force, which, the site explains, offers “protection and support when first responders are unwilling or unable to fulfill their civic duties.” Oltmann characterizes it as a humanitarian group, though he added in an email, “We are all armed.” At one early FEC event, a so-called Patriot Muster, a Trump supporter assaulted and pepper-sprayed a security guard, who shot and killed him. (The guard was charged with second-degree murder and has pleaded not guilty.)

The Coomer story took Oltmann from the small world of right-wing politics in Colorado into broader Republican circles. The same week that he spoke to Jenna Ellis, Oltmann gave an interview about Coomer to Michelle Malkin, a former Fox contributor in Colorado who had joined the even-further-right network, Newsmax.

Around this time, Oltmann began developing his theory of how a voting system could allow for fraud, which he later explained at length in a film called “The Deep Rig”: Someone could manipulate the system in various ways to allow for the possibility of adding fake or phantom ballots, which could be entered into the tabulation system. Real ballots would be replaced with the fake ones without a history of that happening. “It’s clear from the video that Joe Oltmann does not understand how elections are conducted or how the technology works,” says Morrell, who said some of what Oltmann proposed would require a widespread effort of workers from both parties colluding to bypass some key systems.

Thanks to Oltmann and others, the conviction that Dominion had helped rig the election for Joe Biden seemed to solidify among some of Trump’s most loyal supporters. On Thursday, Nov. 12, One America News Network, also known as OAN, ran a story about Dominion. Shortly after that, Trump retweeted: “REPORT: DOMINION DELETED 2.7 MILLION TRUMP VOTES NATIONWIDE,” the first of many times Trump went to Twitter to attack Dominion. Five days later, an OAN correspondent, Chanel Rion, tweeted out Oltmann’s claims about what Coomer supposedly said on that antifa phone call. Then, just eight days after Oltmann first mentioned Coomer on his podcast, Eric Trump broadcast it to its widest audience yet. “Trump’s not gonna win. I made f**ing sure of that!” Eric Trump tweeted, above a photo of Coomer and a link to another Gateway Pundit article that called Coomer, in its headline, “an unhinged sociopath.” (Lawyers for Malkin, Rion, OAN and the Trump campaign, each a defendant in the Coomer lawsuit, did not respond to requests for comment. Lawyers for the Gateway Pundit, another Coomer defendant, declined to comment.)

Rion later invited Oltmann on her show to discuss his claims, and the segment became one of OAN’s highest rated clips, amassing 1.5 million views on YouTube. By then, Eric Coomer’s name started trending on Twitter, along with #ArrestEricCoomer.

On Nov. 19, Poulos, sitting in his office at his home in Toronto, turned on a small television to watch a news conference happening at the Republican National Committee headquarters, which Rudy Giuliani and Sidney Powell were hosting. He knew that Giuliani and Powell had each separately accused Dominion of wrongdoing on Fox News and on right-wing news sites; but he dreaded hearing his company’s name at an event that seemed to have the full legitimacy of the R.N.C. behind it.

After half an hour of watching the event at the R.N.C., what Poulos had feared came to pass: Giuliani referenced hacking “being done by a company that specializes in voter fraud,” then turned the microphone over to Sidney Powell. Powell listed a series of implausible claims about Dominion in deadpan, lawyerly tones, pushing up a sleeve of her leopard-print cardigan as if to show she had real work to do. She spoke of “the massive influence of communist money through Venezuela, Cuba and likely China” on Dominion’s operations.

Poulos says that while he watched, he was in such a state of disbelief that he had to remind himself that what he was seeing was real and not part of a nightmare. “Oh, my God!” he screamed. “I can’t believe what’s going on!” He yelled so loudly that his wife and two teenage children came running into his home office. They found him there, beside himself, crying. His children had never seen him remotely emotional about his work; now they stared, shocked and mute. Poulos felt anger toward Giuliani and Powell for using their power to spread false information. He also felt some sympathy for those voters, disappointed by their candidate’s loss, who would inevitably be eager to believe what they were hearing from people so close to the president. The way many people felt watching the insurrection on Jan. 6, Poulos told me, was how he felt during that news conference. “It was an assault on democracy,” he says.

Powell mentioned Coomer by name, embellishing Oltmann’s story by claiming that there was an actual recording of Coomer on the antifa call. Giuliani brought Coomer up as well. “By the way, the Coomer character, who is close to antifa, took off all of his social media. Aha! But we kept it. We’ve got it. The man is a vicious, vicious man,” Giuliani said. The room where he was speaking was, from all reports, hot and airless; Giuliani was sweating. Brown liquid started snaking down both sides of his face. “He wrote horrible things about the president,” Giuliani continued. “He is completely warped. And he specifically says that they’re going to fix this election. I don’t know what you need to wake you up to do your job!”

When Coomer watched the news conference, he started sweating and shaking; he thought he might vomit. Already, earlier that week, he had met with security officials that Dominion hired, who told him it was not safe for him to go home. The day before the news conference, he had gone back to Colorado, where he had arranged to stay at a friend’s cabin in the mountains.

‘People were essentially taking bets on how my brother’s corpse would be found and which nefarious shadow group would be behind his death.’

Trump’s Bid to Subvert the Election

A monthslong campaign. During his last days in office, President Donald J. Trump and his allies undertook an increasingly urgent effort to undermine the election results. That wide-ranging campaign included perpetuating false and thoroughly debunked claims of election fraud as well as pressing government officials for help.

His arrival had been fraught. When the plane touched down at the airport, Coomer tried to log into his work email, with no success. He texted Poulos to let him know he was having a problem. Poulos reminded him that he had suggested Coomer take a break, which Coomer interpreted to mean he should try to take it easy for a while. He was still helping clients, he reminded Poulos; his boss told him the company would take care of things without him. Only then did Coomer realize that the walls were already going up around him. He was officially on leave, but he suspected that he would never work in elections again.

After he left the airport, he stopped by his home to feed his cats and pick up a rifle. He then drove out of town to his friend’s cabin. It was equipped with surveillance cameras, an elaborate security system and a gun safe; he placed multiple guns around the property, so they would be easily reachable. Then he tried to calm down. He had a lot to figure out, including what he was going to do with the rest of his life.

For several months, Coomer moved around to relieve his isolation, visiting close friends, declining to tell his parents and siblings where he was staying to eliminate the possibility that anyone would slip up and reveal details of his whereabouts to someone who might make them public. Even though all his friends told him watching Oltmann’s show was a terrible idea, he did it anyway — it was a way of staying on top of the situation, of confronting his own fears.

He tracked the story on social media as it moved from Oltmann’s assertion that he had rigged the election to an explanation of how he did it. On right-wing Twitter, a particular story line took off, focusing on the Dominion system of adjudication, which had Coomer’s name, among others, on the patent. Like all digital-adjudication systems, Dominion’s allowed election officials to set various parameters to determine at which point a ballot — if it had additional writing on it or only partially-filled ovals — would be directed to a bipartisan panel that would then agree, based on state standards, on voter intent. Rather than making a new paper ballot, the system would create a digital record of the new adjudicated result while preserving the original digital record. In one widely circulated video, Coomer was walking election officials through the ways they could use it, using the first person to describe the various steps, which suspicious viewers took literally, as if he were letting the officials know how he, personally, could change the adjudication settings.

In the latter half of November, a letter arrived at his parents’ home with a handwritten profanity scrawled at the bottom, telling them their son would suffer in jail. His father, now 80, began carrying a weapon on his person, even at home. They received two calls in the middle of the night, strangers asking to speak to Eric.

Coomer’s parents had already suffered more grief than most do in a lifetime. Their daughter died in a car accident when she was only 9 and Coomer was 22. Nine years ago, his older sister, who worked as a paralegal and a teacher, also died, at age 47, after a long illness. Coomer felt powerless: He could not protect his family from harassment, could not spare them further worry for the safety of one of their children. “I’m so sorry,” he told them over and over.

Coomer stopped returning friends’ calls, was sleepless at night and suffered from panic attacks during the day. Occasionally, he returned home for a few hours. On one occasion in mid-December, two men pulled up to the house. Did they follow him there or just get lucky? He had no idea, but he grabbed a gun. One of the men walked around the perimeter of his house; the other came right to the door, peering in the large window. One had a video camera. “Has anybody from the D.O.J. tried to contact you?” the man called out, in Coomer’s recollection. “We just want to know why you threw the election. Do you have a few minutes to talk?” Coomer told them to leave — they were trespassing. Twenty minutes after they left, he got a voice-mail message: One of the men identified himself as a journalist for a right-wing news site, now calling to follow up.

In December, as Trump’s various lawsuits were starting to be dismissed in court, Oltmann began posting more menacing messages. “Eric Coomer, you are a traitor,” he wrote. “We are coming for you and your shitbag company.”

On Dec. 8, Coomer responded to some of the attacks. In an op-ed for The Denver Post, he called out the “fringe media personalities” who “continue to prey on the fears of a public concerned about the safety and security of our electoral system.” He also claimed that “any posts on social media accounts purporting to be from me have also been fabricated.” And yet, Coomer had written the posts that Oltmann had highlighted. Asked about the misleading language, Coomer concedes that his writing could have been clearer but says he was referring to social media purporting to be his that were posting at the time (his own Facebook account was no longer active). The column did not help Coomer’s credibility among those inclined to mistrust him already.

His name, virtually unknown in most mainstream circles, was now tightly linked with the story of Dominion fraud, especially among QAnon followers: According to the nonpartisan and nonprofit group Advance Democracy Inc., from Nov. 1 to Jan. 7, Coomer’s name appeared in 25 percent of the tweets that mentioned Dominion in its database of QAnon-related accounts.

On Dec. 22, Coomer filed his defamation lawsuit. “Together, defendants conceived of a story that the results of the election were fraudulent and consciously set out to establish that Dr. Coomer perpetuated this fraud so as to further their own ends,” the amended complaint reads. All the claims they made about Coomer started with Oltmann: It was his story about Coomer being on an antifa call that Eric Trump retweeted, that Giuliani and Powell trumpeted at the Nov. 19 event at the R.N.C. Their defense would rest on the credibility of Oltmann’s claim or at least some proof that it had a basis in reality.

The day before the defamation lawsuit was filed, Oltmann reported on his podcast that the F.B.I. had been asking questions about him, although he did not specify why. Dominion, too, sent him a letter demanding that he retract his statements and preserve all records related to his repetition of the “outlandish story that you infiltrate(d) Antifa.”

Early in the new year, Oltmann was gearing up for the rallies planned before the ascertainment of the election on Jan. 6. “Do not tell me you are tired,” he wrote in a post that 1,001 people liked. “I’m here to tell you we are winning this fight against evil. Now stand the hell up, run some dirt in it, and don’t stop till the evil is crushed with the heel of your shoe. ... we are the warriors who MUST stand up to the evil we face.”

On Jan. 5, at a rally on Freedom Plaza in Washington, a series of anti-vaxxers, conspiracy theorists, Soros-haters and Trump supporters addressed a large crowd. “If they want to fight, they better believe they’ve got one!” the right-wing radio host Alex Jones roared. Peter Navarro, a White House adviser, whipped the crowd into a frenzy about the supposedly false election. And then finally, following Roger Stone, the last speaker of the day stepped up to the lectern: Oltmann. He was introduced as a businessman, a data expert and, “most importantly, the guy who found and fingered Eric Coomer.” Oltmann tried to talk the crowd through a flowchart presentation involving tabulation systems and fake ballots. But by far the biggest response he got was when he mentioned Coomer. “Eric Coomer is suing me,” he said. “I’m going to crush him in discovery.” The crowd roared.

Later, Oltmann described, in various podcast interviews, what happened during his time in Washington. On Jan. 6, he claims that he went to the State Department to talk to a lawyer who worked with Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to explain what he’d uncovered. (“They said, ‘If this is true ... this is a coup!’ I said, ‘Well, that’s exactly, that’s what I would call it!’” he recalled.) He also claimed that he met with John Eastman, a lawyer who was arguing to Trump’s team that Pence could legally reject the election. Oltmann claimed that he fed Eastman the theory of election fraud that he presented at the rally on Jan. 6 near the Ellipse, where Trump spoke shortly before a crowd stormed the Capitol.

Oltmann also said he asked Giuliani to arrange a meeting with Trump to walk him through the same theory of election fraud he had been presenting to others. “I was like, ‘Look, just put me in front of President Trump,’” Oltmann recalled, claiming that Giuliani and others arranged for him to have that meeting on the Jan. 7. (In a deposition, Giuliani said he did not believe he had met Oltmann, but he could not be sure.) But the day after the insurrection, doors that had perhaps once been open were now closed. “There were people who stopped me from having those meetings with President Trump on the 7th,” Oltmann told one podcaster. “We were dealing with a compromised group of people who don’t understand what courage is.”

Instead of meeting with the president, Oltmann said, he received a call from an executive at PIN, who was calling to tell him that he had lost the confidence of the board. Oltmann stepped down. He called it a “sad day and something that is driving my fire to get to the bottom of the truth.”

In those first weeks at his friend’s cabin, Coomer sometimes felt rage at all that had been taken from him. Often he lay awake all night, trying to determine if he heard sounds outside. Following the violent events of Jan. 6, Coomer decided to leave the country ahead of the inauguration. He remained abroad for three weeks, finding respite in a whole world full of people whom he could be fairly sure had never heard of him.

In late April, Coomer decided to take a three-week camping trip with no access to email or text messages. On May 14, when he was again within range of a cellphone tower, his phone started pinging, over and over and over. Congratulations, many of the texts read; but he was also receiving texts and voicemails that reminded him of what he’d left behind — harassment, comments from hostile strangers that arrived on his phone telling him, one way or another, that he was going to jail.

Coomer was receiving a new onslaught of attention because Newsmax, which had originally been named in his defamation lawsuit, had decided to settle. It also issued an apology, acknowledging that it had found “no evidence” to support the claims the network aired about Coomer’s influencing the election. Coomer felt some relief: It sometimes had seemed that there would never be any accountability, for anyone, ever. But at the same time the number of hostile texts he received reminded him that no settlement was likely to put an end to his ordeal.

In May, Coomer formally left Dominion after negotiating “a mutually agreed-upon separation” with them. It was, he says, a surreal day: One more reminder that his life had changed irrevocably.

By June, a dossier on Coomer that was more than a hundred pages long began making the rounds on Telegram. It included links to writing Coomer posted as a 20-something about the loss of his younger sister; it included photos of his ex-wife and five possible email addresses for her and listed what it claimed were the make and model of his brother’s car; it proposed a far-fetched theory that Coomer’s animus toward Trump was because of political decisions that hurt his brother’s employer. It also included a link to the essay Coomer had posted on a climbing message board in which he spoke frankly of his drug addiction and where he mentioned, in a back and forth with commenters, a mental-health disorder (although Coomer now says he was never clinically diagnosed). Even before he saw the dossier, Coomer knew from his incoming texts and emails, which overflowed with threats, that something new was out there, continuing to stoke people’s anger.

On Aug. 11, Oltmann was scheduled to be deposed by Coomer’s lawyers for the defamation suit. Coomer arrived at the state courthouse in Denver early that morning; it would be the first time he would be in the same room with Oltmann.

Coomer sat with his lawyer, Steve Skarnulis, who had flown in from Austin, and two other lawyers. At 9 a.m., Oltmann’s lawyer told them that Oltmann would not be appearing in court because he didn’t feel safe in the courthouse. (His lawyer, Andrea Hall, had offered to do the deposition via Zoom.) The judge was compelling him to reveal the name of the person who brought him in on the antifa conference call, and even though the court agreed the name would remain sealed, Oltmann had refused — for that person’s safety and his own, he said. Now he was afraid that if he were put in jail for contempt, he would be “dead within 72 hours,” Hall, told me.

In the previous weeks, the judge assigned to Oltmann’s case made rulings that did not cut in his favor, including allowing Coomer’s legal team to do preliminary discovery with the various defendants. Coomer’s lawyers have also deposed Powell and Giuliani about their roles in spreading their conspiracy theories about Coomer and Dominion.

“The judge has become an activist judge,” Oltmann said on an episode of “Conservative Daily” in July. “She’s allowing things to go forward that should not have been allowed to come forward.” At times, the weight of the charges seems to weigh heavily on him. “I don’t want to get to the place where I feel sorry for myself,” Oltmann said during a special three-part “Conservative Daily” podcast on the topic of the Coomer suit. He sounded emotional. “I don’t feel sorry for myself.”

Oltmann says that he, like Coomer, has been the subject of death threats. On his podcast, though, he continues to push an ever-grander theory of election fraud. The more viewers Oltmann attracts, the bigger his audience for a service he promotes on his show, the so-called Fax Blast, in which users can pay to have faxes sent to various legislators on their behalf. This spring, he started attracting advertisers as well, including MyPillow, a business owned by Mike Lindell, who is also being sued by Dominion for his statements accusing the company of rigging the election. (Previously one of the biggest advertisers on Fox News, Lindell has been boycotting the network since they refused to air an advertisement claiming election fraud. He did not respond to a request for comment.)

The number of hostile texts he received reminded him that no settlement was likely to put an end to his ordeal.

Instead of showing up in court on that August morning, Oltmann was in South Dakota, at a cybersecurity symposium hosted by Lindell, who at one point rushed offstage when it was announced that his motion to dismiss Dominion’s defamation had been rejected. Steve Bannon, who was also at the event, interviewed Oltmann on his podcast, “Bannon’s War Room.” “I think people are asking,” Bannon said to Oltmann, “if it’s a lawsuit and you think you’ve got the truth and law on your side, why would you not show up for a deposition?” The judge, Oltmann explained, was appointed by Jared Polis, a Democrat.

Coomer is finding little comfort in the slow movement of the judicial process. He has started a new business, but he is not yet publicly disclosing what it is. He is still prone to panic attacks. In August, he was disturbed to find out that Jennifer Morrell had been receiving threats after the Gateway Pundit ran a 2018 photo of her at a barbecue at Coomer’s home.

For her part, Morrell says that she misses being able to consult with Coomer on election matters. Earlier this spring, Morrell says, she was struggling to understand a technicality involved in a new audit procedure for a state that hired her. She briefly thought of calling Coomer for clarification, but she realized that talking to him was no longer an option, even if he had still been working in the industry. Talking to Coomer, she worried, could leave her client vulnerable. “There’s this concern — I don’t want any phone record,” she said. “Even though everything seemed crazy and outlandish, and you knew it was false and built on lies and conspiracy — you didn’t want to do anything that could jeopardize other places where you are providing support.”

Although Coomer’s case was especially severe, most election officials she knew had been receiving, since the election, death threats or hateful messages. One colleague had photos of her children sent to her, along with threatening notes, and now had security outside her home. Following earlier mentions of her election work in the press, Morrell had received a flurry of misogynist, violent texts. A message sent to her via her company’s website said that “the Caucasian founding fathers gave us a second amendment to use against the enemies of this nation ... We fully intend to exercise this amendment to rid our society of you and your ilk.”

Morrell says she regularly gets calls from state or local election officials who say they are losing staff. The Times recently reported that 25 percent of the directors or deputy auditors of elections in 14 counties in Ohio have left their jobs. The loss of so much institutional knowledge and expertise, the sheer shortage of workers, is another challenge facing an already frail election system.

Coomer said he no longer wakes up every hour wondering if someone is outside his home. “But in some ways, it’s gotten worse,” he said. When the campaign against him started, he feared for his safety, but he thought the danger would be temporary. But nine months later, he had to accept that the changes to his life were permanent: “Now it’s almost becoming a mainstream accepted narrative that I helped rig an election.” Millions of people now believed that story, and it was how history — or certain authors and readers of history — would forever remember him.

If what happened in Antrim County was one case study in the power of malinformation, Coomer’s is another. “I think Dominion as a company would be facing all of the same things they are right now without me,” Coomer said. “But I was an accelerant. And for lack of a better word, I was a perfect villain.”

Bryan Schutmaat is a photographer based in Austin, Texas, who has won numerous awards, including a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial fellowship, the Aperture Portfolio Prize and an Aaron Siskind fellowship.