MOUNTAIN VIEW, Calif. — Google’s first office was a cluttered Silicon Valley garage crammed with desks resting on sawhorses.

In 2003, five years after its founding, the company moved into a sprawling campus called the Googleplex. The airy, open offices and whimsical common spaces set a standard for what an innovative workplace was supposed to look like. Over the years, the amenities piled up. The food was free, and so were buses to and from work: Getting to the office, and staying there all day, was easy.

Now, the company that once redefined how an employer treats its workers is trying to redefine the office itself. Google is creating a post-pandemic workplace that will accommodate employees who got used to working from home over the past year and don’t want to be in the office all the time anymore.

The company will encourage — but not mandate — that employees be vaccinated when they start returning to the office, probably in September. At first, the interior of Google’s buildings may not appear all that different. But over the next year or so, Google will try out new office designs in millions of square feet of space, or about 10 percent of its global work spaces.

The plans build on work that began before the coronavirus crisis sent Google’s work force home, when the company asked a diverse group of consultants — including sociologists who study “Generation Z” and how junior high students socialize and learn — to imagine what future workers would want.

The answer seems to be Ikea meets Lego. Instead of rows of desks next to cookie-cutter meeting rooms, Google is designing “Team Pods.” Each pod is a blank canvas: Chairs, desks, whiteboards and storage units on casters can be wheeled into various arrangements, and in some cases rearranged in a matter of hours.

To deal with an expected blend of remote and office workers, the company is also creating a new meeting room called Campfire, where in-person attendees sit in a circle interspersed with impossible-to-ignore, large vertical displays. The displays show the faces of people dialing in by videoconference so virtual participants are on the same footing as those physically present.

In a handful of locations around the world, Google is building outdoor work areas to respond to concerns that coronavirus easily spreads in traditional offices. At its Silicon Valley headquarters, where the weather is pleasant most of the year, it has converted a parking lot and lawn area into “Camp Charleston” — a fenced-in mix of grass and wooden deck flooring about the size of four tennis courts with Wi-Fi throughout.

There are clusters of tables and chairs under open-air tents. In larger teepees, there are meeting areas with the décor of a California nature retreat and state-of-the-art videoconferencing equipment. Each tent has a camp-themed name such as “kindling,” “s’mores” and “canoe.” Camp Charleston has been open since March for teams who wanted to get together. Google said it was building outdoor work spaces in London, Los Angeles, Munich, New York and Sydney, Australia, and possibly more locations.

Employees can return to their permanent desks on a rotation schedule that assigns people to come into the office on a specific day to ensure that no one is there on the same day as their immediate desk neighbors.

Despite the company’s freewheeling corporate culture, coming into the office regularly had been one of Google’s few enduring rules.

That was a big reason Google offered its lavish perks, said Allison Arieff, an architectural and design writer who has studied corporate campuses. “They get to keep everyone on campus for as long as possible and they’re keeping someone at work,” said Ms. Arieff, who was a contributing writer for the Opinion section of The New York Times.

But as Google’s work force topped 100,000 employees all over the world, face-to-face collaboration was often impossible. Employees found it harder to focus with so many distractions inside Google’s open offices. The company had outgrown its longtime setup.

In 2018, Google’s real estate group began to consider what it could do differently. It turned to the company’s research and development team for “built environments.” It was an eclectic group of architects, industrial and interior designers, structural engineers, builders and tech specialists led by Michelle Kaufmann, who worked with the renowned architect Frank Gehry before joining Google a decade ago.

Google focused on three trends: Work happens anywhere and not just in the office; what employees need from a workplace is changing constantly; and workplaces need to be more than desks, meeting rooms and amenities.

“The future of work that we thought was 10 years out,” Ms. Kaufmann said, “Covid brought us to that future now.”

Two of the most rigid elements in an office design are walls and the heating and cooling systems. Google is trying to change that. It is developing an array of different movable walls that can be packed up and shipped flat to offices around the world.

It has a prototype of a fabric-based overhead air duct system that attaches with zippers and can be moved over a weekend for different seating arrangements. Google is also trying to end the fight over the office temperature. This system allows every seat to have its own air diffuser to control the direction or amount of air blowing on them.

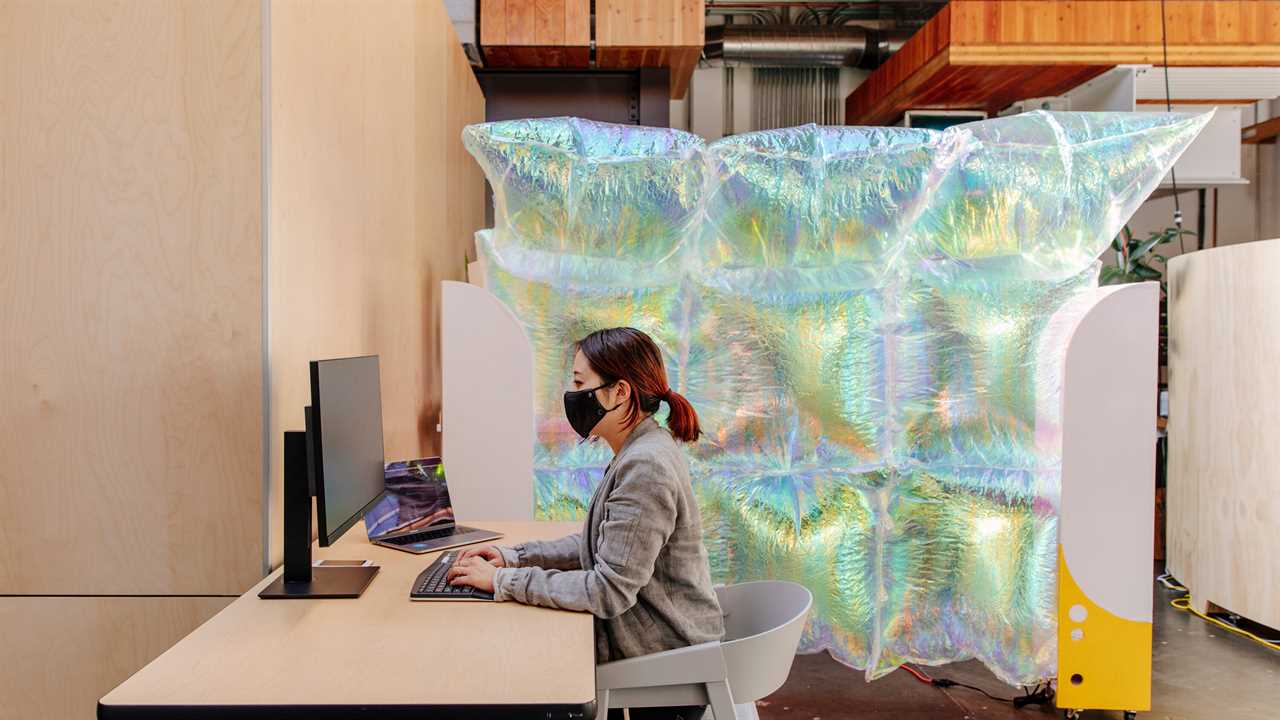

If a meeting requires privacy, a robot that looks like the innards of a computer on wheels and is equipped with sensors to detect its surroundings comes over to inflate a translucent, cellophane balloon wall to keep prying eyes away.

“A key part of our thinking is moving from what’s been our traditional office,” said Ms. Kaufmann.

Google is also trying to reduce distractions. It has designed different leaf-shaped partitions called “petals” that can attach to the edge of a desk to eliminate glare. An office chair with directional speakers in the headrest plays white noise to muffle nearby audio.

For people who may no longer require a permanent desk, Google also built a prototype desk that adjusts to an employee’s personal preferences with a swipe of a work badge — a handy feature for workers who don’t have assigned desks because they only drop into the office once in a while. It calibrates the height and tilt of the monitor, brings up family photos on a display, and even adjusts the nearby temperature.

In the early days of the pandemic, “it seemed daunting to move a 100,000-plus person organization to virtual, but now it seems even more daunting to figure out how to bring them back safely,” said David Radcliffe, Google’s vice president for real estate and workplace services.

In its current office configurations, Google said it would be able to use only one out of every three desks in order to keep people six feet apart. Mr. Radcliffe said six feet would remain an important threshold in case of the next pandemic or even the annual flu.

Psychologically, he said, employees will not want to sit in a long row of desks, and also Google may need to “de-densify” offices with white space such as furniture or plants. The company is essentially unwinding years of open-office plan theory popularized by Silicon Valley — that cramming more workers into smaller spaces and taking away their privacy leads to better collaboration.

Real estate costs for the company aren’t expected to change very much. Though there will be fewer employees in the office, they’ll need more room.

There will be other changes. The company cafeterias, famous for their free, catered food, will move from buffet style to boxed, grab-and-go meals. Snacks will be packed individually and not scooped up from large bins. Massage rooms and fitness centers will be closed. Shuttle buses will be suspended.

Smaller conference rooms will be turned into private work spaces that can be reserved. The offices will use only fresh air through vents controlled by its building management software, doing away with its usual mix of outside and recirculated air.

In larger bathrooms, Google will reduce the number of available sinks, toilets and urinals and install more sensor-based equipment that doesn’t require touching a surface with hands.

A pair of new buildings on Google’s campus, now under construction in Mountain View, Calif., and expected to be finished as early as next year, will give the company more flexibility to incorporate some of the now-experimental office plans.

Google is trying to get a handle on how employees will react to so-called hybrid work. In July, the company asked workers how many days a week they would need to come to the office to be effective. The answers were divided evenly in a range of zero to five days a week, said Mr. Radcliffe.

The majority of Google employees are in no hurry to return. In its annual survey of employees called Googlegeist, about 70 percent of roughly 110,000 employees surveyed said they had a “favorable” view about working from home compared with roughly 15 percent who had an “unfavorable” opinion.

Another 15 percent had a “neutral” perspective, according to results viewed by The New York Times. The survey was sent out in February and the results were announced in late March.

Many Google employees have gotten used to life without time-consuming commutes, and with more time for family and life outside of the office. The company appears to be realizing its employees may not be so willing to go back to the old life.

“Work-life balance is not eating three meals a day at your office, going to the gym there, having all your errands done there,” said Ms. Arieff. “Ultimately, people want flexibility and autonomy and the more that Google takes that away, the harder it is going to be.”

Google has offices in 170 cities and 60 countries around the world, and some of them have already reopened. In Australia, New Zealand, China, Taiwan and Vietnam, Google’s offices have reopened with occupancy allowed to exceed 70 percent. But the bulk of the 140,000 employees who work for Google and its parent company, Alphabet, are based in the United States, with roughly half of them in the Bay Area.

Sundar Pichai, chief executive of Alphabet, said at a Reuters conference in December that the company was committed to making hybrid work possible, because there was an opportunity for “tremendous improvement” in productivity and the ability to pull in more people to the work force.

“No company at our scale has ever created a fully hybrid work force model,” Mr. Pichai wrote in an email a few weeks later announcing the flexible workweek. “It will be interesting to try.”