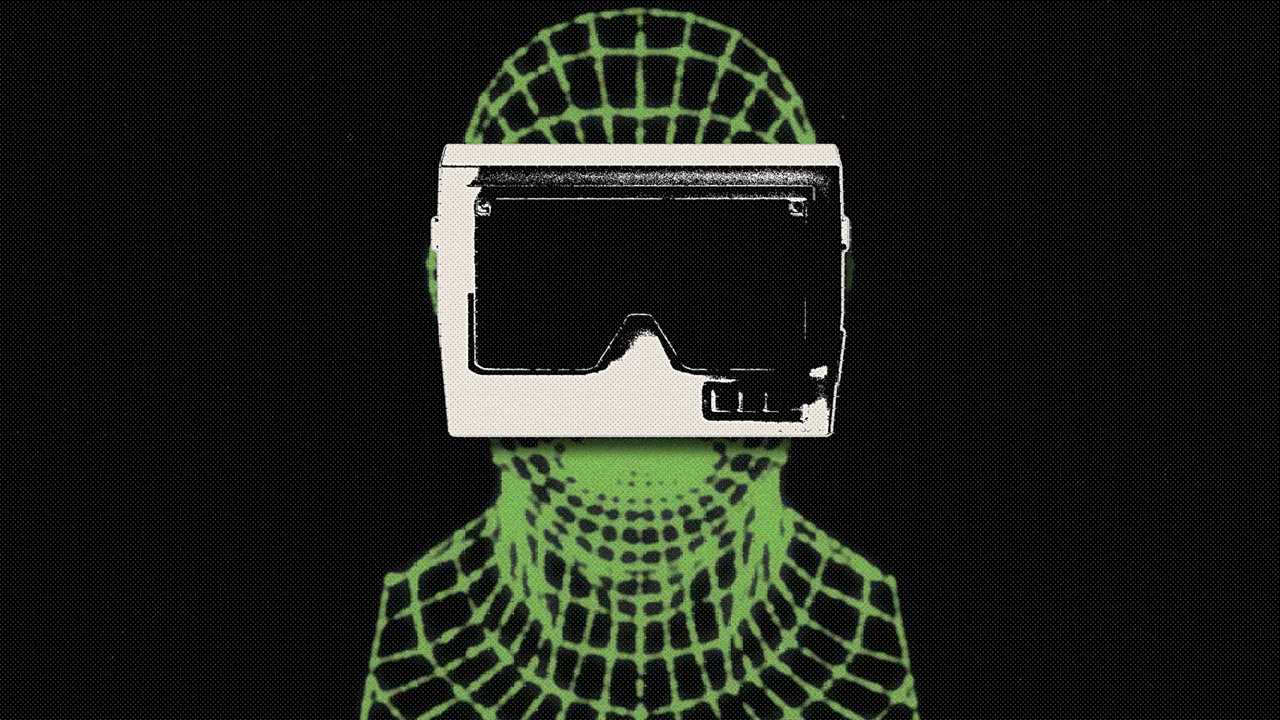

If the tech predictions pan out, we’ll soon be wearing computers on our faces and plugging into immersive realms of virtual people and places, perhaps blended with the real world around us.

(I don’t want to use the buzzword “metaverse” here, because ugh. This term from science fiction has been applied to anything and everything that we should just call . But that’s partly what I’m talking about.)

I am both apprehensive and excited about the potential next generation of technologies that may further blur the lines between computers and us, and between online and real life. I can get into the idea of glasses that let me scroll restaurant menu items and feel as if the sizzling burger is in front of me, or into headgear that lets me exercise next to a virtual lake in Patagonia.

No one can predict how long it might take this imagined future of the internet to come true and go mainstream, if it ever does. But if computers on our faces and more lifelike digital realities are coming for us, let’s start thinking through the implications

I don’t have a fleshed out good humans’ guidebook for the metaverse. (Ugh, that word again.) But I know that instead of letting Mark Zuckerberg or the Apple chief executive Tim Cook decide on the etiquette, ethics, norms, rewards and risks of our potential brave new world of technology, we need to do it.

How we use technology shouldn’t be left to the companies that dream up electronics and software. It should be up to us, individually and collectively. That can happen by deliberate thought and careful design, or by the lack of it.

I’m writing this now because Apple reportedly plans to introduce its first computers for the face in the next year or so.

Apple appears to imagine that its face computers — similar to Microsoft’s HoloLens, Snap’s experimental Spectacles or the failed Google Glass — will blend virtual images with the world around us, sometimes called “augmented reality.” Imagine watching a fix-it video of a car engine while a guide overlays diagrams on the fan belt that you’re trying to repair.

Apple has a reputation for making up-and-coming technology go mass market. We’ll see, but it’s clear that there will be a lot of activity and attention on face computers and immersive technologies in all forms. (Counterpoint: Some tech experts have predicted the rise of face computers for most of the past decade.)

What I want all of us to do — whether we don’t get the fuss over virtual reality or love it — is to begin deliberating over where we want to focus the promise of this technology and limit the risks.

I’m mindful of what has gone wrong when we allowed technology to wash over us and tried to figure out the details later.

Partly through an unwillingness or inability to imagine what could go wrong with technology, we have websites and apps that track us everywhere we go, and that sell the information to the highest bidders. We have carmakers that sometimes protect us with clever tech that helps offset human frailties, and other times seem to exacerbate them. We have the best aspects of human interactions online, and the worst.

We should think about this stuff now, before we might all be wearing supercomputers on our faces.

What do want from this technology? Can we imagine schools, offices or comedy clubs in virtual reality? What do we want from the next generation of immersive internet for our kids? Do we want to drive while our headgear flings tweets into our fields of vision? Do we even want to erase the gap between digital life and real life?

Understand the Facebook Papers

A tech giant in trouble. The leak of internal documents by a former Facebook employee has provided an intimate look at the operations of the secretive social media company and renewed calls for better regulations of the company’s wide reach into the lives of its users.

It might be misguided to establish norms and laws around technologies that might take many years to become big. But tech companies and technologists aren’t waiting. They’re molding their imagined future of the internet now. If we don’t engage, that puts the companies in the driver’s seat. And we’ve seen the downside of that.

Before we go …

Tracking the Chinese propaganda and censorship machine: After the Chinese tennis star Peng Shuai accused a former high-ranking government official of sexual assault, she vanished from public life. My colleagues and ProPublica analyzed how Chinese state media, amplified by a network of fake social media accounts, circulated messages that Shuai was safe and free.

Reading this will make you hungry: One man has made it his mission to have Mexico City’s street food vendors listed in Google Maps, Rest of World reported.

A gazillion speedy delivery apps. With similar fonts: A brand expert writes for Bloomberg Opinion about the similar italics, avocado photos and “bed-headed, bucket-hatted ‘cheat day’ mood of indulgence” used by start-ups like Gopuff, Getir, Fridge No More and Jokr that deliver convenience and grocery items in 15 minutes or less.

Hugs to this

“Behold the fearsome Tyrannosaurus rex — all swaddled in a cozy Christmas sweater.”