AFTER STEVE: How Apple Became a Trillion-Dollar Company and Lost Its Soul, by Tripp Mickle

Between 2001 and 2010, Apple launched the iPod, the iPhone, the MacBook Air and the iPad; each redefined its product category. Of these, the iPhone was the most important. Its obvious superiority forced every other company selling expensive phones to copy Apple’s design or collapse. (Nokia, BlackBerry and Palm were gutted within years.) The Apple of 2010, at the end of its , had a record of hardware innovation no other electronics firm could match. Including the Apple of 2020.

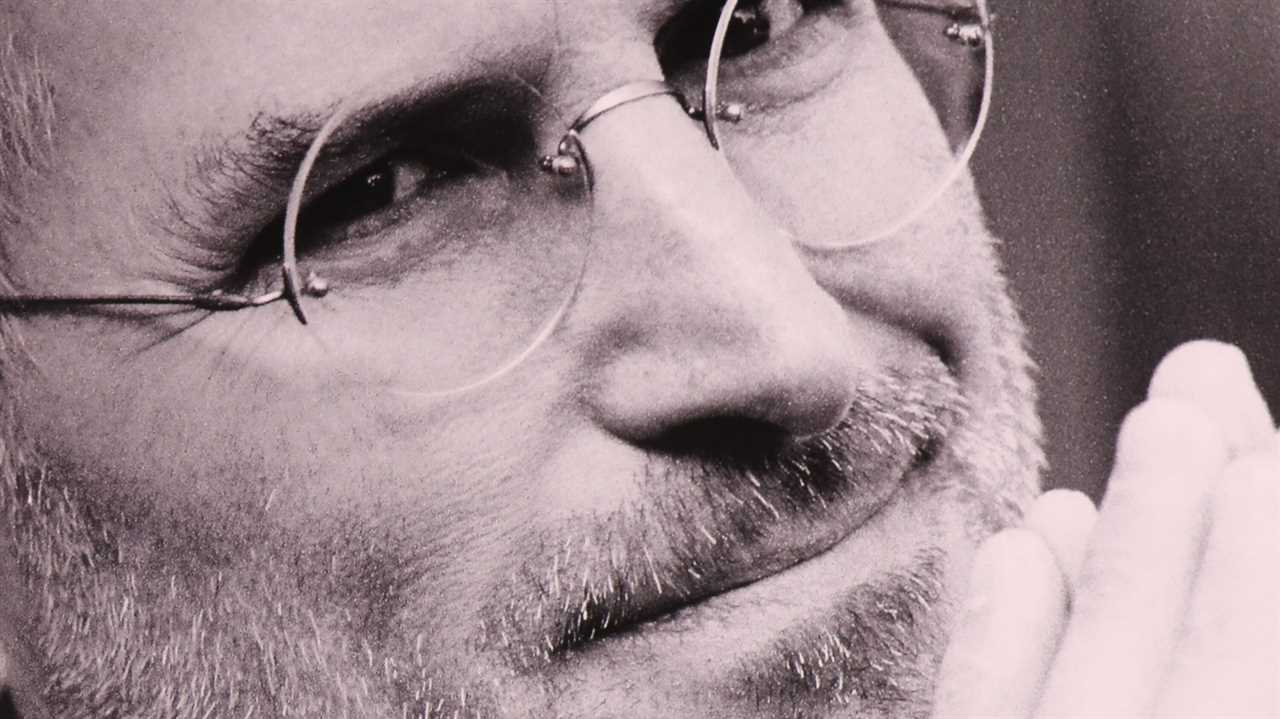

Steve Jobs, Apple’s co-founder and animating spirit, died in 2011, leaving the firm in the hands of Jony Ive, the British-born designer-savant, and Tim Cook, a child of Alabama who’d become a master of supply chains and production costs. “After Steve,” by the Wall Street Journal reporter Tripp Mickle, covers Ive’s and Cook’s careers, and how they and the company changed after they took over.

The book traces the evolution and end of Ive and Cook’s partnership, involving compendious review of public sources and over 200 interviews with current and former Apple employees and advisers; the cast of characters itself runs to four pages. Some of this technique is in response to Apple’s “culture of omertà” — apparently, neither Ive nor Cook agreed to speak to the author for attribution — but Mickle uses comparative descriptions to sketch out their differences, like how Ive drives to work in a bright yellow Saab, Cook in a drab Honda Accord.

Both men helped save a sinking Apple in the 1990s — Ive first, overseeing the design of a new line of computers with candy-colored transparent cases. When the iMac launched in 1998, Jobs unveiled Ive’s creation by pulling a sheet off it, as if it were a sculpture, saying, “It looks like it’s from another planet, a good planet with better designers.” Those eye-catching iMacs improved the company’s public perception, staff morale and bottom line all at once. Apple was saved. Now it just had to grow.

That same year, Jobs tapped Cook to rework Apple’s inefficient production line. Cook, who’d previously run the supply chain for Compaq, was famously demanding and detail-oriented. When his staff presented a plan to increase inventory turnover from 25 times a year to 100 to save money on “spoiling parts,” Cook calmly asked, “How would you get to a thousand?” Joe O’Sullivan, who was running operations when Cook arrived, said, “I saw grown men cry. … He went into a level of detail that was phenomenal.”

Ive was also demanding, of both his colleagues and external suppliers. In one meeting, shown a piece of polished aluminum for a laptop case, Ive became visibly upset at imperfections barely visible to the others. Seeking to calm him, one of his colleagues handed him a red Sharpie, telling Ive to circle what was wrong. “I’ve got a different idea,” came Ive’s reply. “Get me a bucket of red paint. I’ll dip this in it and wipe off the things that are right.” Ive was not just a perfectionist but a corporate infighter as well. He revoked engineers’ access to the design wing if they talked too loudly or mentioned costs. This sort of behavior was so widely known, a source in H.R. told Mickle they’d sometimes physically hidden staff from Ive to keep them from getting fired.

Perfectionism isn’t enough to create a great product, however. After Jobs’s death, there was uncertainty about what the Next Big Thing might be. Home automation, health care devices, self-driving cars, televisions and various headphones were all explored, and some launched. But for most of Ive’s remaining tenure, the centerpiece of Apple’s device work — and therefore of Mickle’s book — would be the Apple Watch.

Ive had been the key figure in product design for years, but in his elevated role, Mickle writes, “designers defined how a product would look and had an outsize voice in its functions. Staff began summarizing their power in a single phrase: ‘Don’t disappoint the gods.’” Apple’s wealth underwrote Ive’s perfectionism. Leather for the wristband was sourced from tanneries across Europe; countless hours were poured into the design and manufacture of the customized winding crown. Determined from the beginning to make ultraexpensive versions, Ive requested — and got — a new 18-karat alloy that was twice as durable as ordinary gold.

Yet as the story unfolds, it becomes clear the watch will not be the Next Big Thing. As Ive acquires more control than he had over the iPhone, the watch shifts from a useful screen on your wrist into a fashion object. Meetings with the Vogue editor Anna Wintour, a product event in Paris and the creation of a $17,000 model run alongside gradually reduced expectations for its health tracking and battery life. By the time it finally launches and sales fall short of projections, the reader has seen it coming, one decision at a time.

In contrast to Ive’s big project, Cook faced a welter of events. He was called before Congress over taxes. He had to apologize for poor performance in the earliest iteration of Apple Maps. The Samsung Galaxy, an iPhone competitor, regularly burst into flames. China’s largest telecom, China Mobile, signaled interest in selling iPhones. In 2014, Cook made history in Bloomberg Businessweek, writing, “While I have never denied my sexuality, I haven’t publicly acknowledged it either, until now. So let me be clear: I’m proud to be gay, and I consider being gay among the greatest gifts God has given me.” He was the first C.E.O. of a Fortune 500 company to come out. And of course, in 2018, he became the first leader of a public company worth a trillion dollars. Then two trillion. Then three.

Mickle builds a dense, granular mosaic of the firm’s trials and triumphs, showing us how Apple, built on Ive’s successes in the 2000s, became Cook’s company in the 2010s. Ive, long since knighted, becomes increasingly captivated by opportunities outside Apple — a museum exhibition, a charity auction, an immersive Christmas tree installation — and goes part time in 2015. Realizing this is worse than having Ive either fully present or absent, Cook persuades him to come back, but his heart clearly isn’t in it. Finally, in 2019, Ive leaves for good.

In the epilogue, Mickle drops his reporter’s detachment to apportion responsibility for the firm’s failure to launch another transformative product. Cook is blamed for being aloof and unknowable, a bad partner for Ive, “an artist who wanted to bring empathy to every product.” Ive is also dinged for taking on “responsibility for software design and the management burdens that he soon came to disdain.” By the end, the sense that the two missed a chance to create a worthy successor to the iPhone is palpable.

It’s also hooey, and the best evidence for that is the previous 400 pages. It’s true that after Jobs died, Apple didn’t produce another device as important as the iPhone, but Apple didn’t produce another device that important he died either. It’s also true that Cook did not play the role of C.E.O. as Jobs had, but no one ever thought he could, including Jobs, who on his deathbed advised Cook never to ask what Steve would do: “Just do what’s right.”

Ive and Cook wanted another iPhone, but, as Mickle’s exhaustive reporting makes clear, there was not another such device to be made. Self-driving cars were too hard, health devices too regulated, television protected in ways music had not been, and even the earbuds and watch, devices they actually shipped, were peripheral, technically and conceptually, to Apple’s greatest product.

Epilogue aside, the book is an amazingly detailed portrait of the permanent tension between strategy and luck: Companies make their own history, but they do not make it as they please. What happened after Steve was that Cook’s greatest opportunities were in Apple’s future, Ive’s in its past. When the Next Big Thing turned out to be services — iCloud, Apple Music, the App Store — built on top of the Last Big Thing, Cook adapted brilliantly. He took Jobs’s advice and did what was right, but in ways that put less of a premium on the kind of work Ive was best at. The moral of that story is there is no moral. Even one of the richest, most beloved firms in the world could not make its most talented employees successful at the same time.

Clay Shirky is a professor at N.Y.U. and the author, most recently, of “Little Rice: Smartphones, Xiaomi, and the Chinese Dream.”

AFTER STEVE

How Apple Became a Trillion-Dollar Company and Lost Its Soul

By Tripp Mickle

495 pp. William Morrow. $29.99.