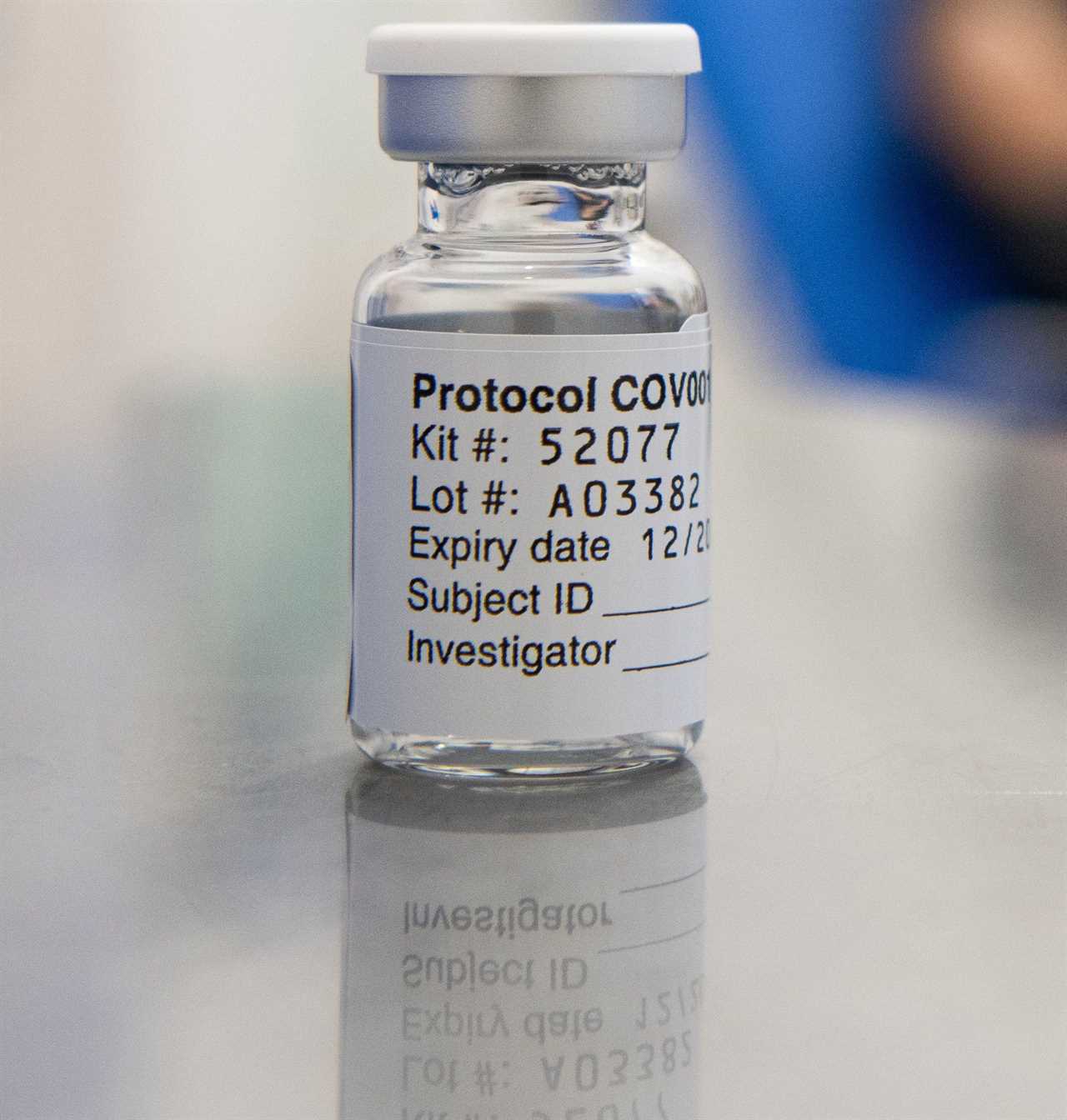

IT took Emma Bolam nearly four hours to painstakingly place tiny virus particles into 500 vials to create the first vaccines for Covid-19.

Head to toe in protective clothing and wearing three pairs of gloves, she filled the first batch of the treatment which reached “efficacy” last weekend — proving it stops people falling ill.

When we visited the Oxford University team this week, we discovered head of production Emma is among hundreds of specialists who have been working round the clock to help save lives.

Emma, 49, said: “Getting to this stage in nine months has been record breaking and so exciting. It’s never been done before and I’m so proud of the team.

“We filled the first batch of vaccine on April 2. I was working at an isolator with filtered, sterile air.

“I manually filled 500 vials with half a millilitre in each. It had to be the exact amount.

“Then I put a stopper in each vial. My colleague sat beside me, crimping the metal seal on top of them. It was nerve wracking. So much depended on it.”

Emma has helped produce several vaccines at the Clinical BioManufacturing Facility run by Professor Cath Green — and ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 has been her toughest assignment yet.

She worked long hours, even buying son Alex, 12, an electric scooter to say sorry for spending so little time with him of late.

She has not seen her “proud” parents, Chris and Toni in Wales, since last Christmas as they don’t do Zoom, or her sister. She won’t see them this Christmas, either.

Mixing is “madness” until the vaccine is being administered, she says, but a get-together is planned for spring.

She added: “All the sacrifices have been worth it.”

They certainly have. Last Monday, the world heard the UK’s Covid vaccine — from AstraZeneca and Oxford University — was highly effective in advanced trials.

It gave hope of another jab, one cheaper and easier to distribute than the impressive Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna mRNA vaccines unveiled days earlier.

The University of Oxford’s Jenner Institute and Oxford Vaccine Group have been developing vaccines for more than 30 years.

But before Professor Green’s team could produce the latest, Sarah Gilbert, 58 — the lead researcher of the development programme and professor of vaccinology at Oxford — had to create the formula.

She has worked on vaccines for MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome) and Lassa fever.

She also helped develop an Ebola vaccine after the 2014 outbreak, although the epidemic was nearly over by the time it was ready.

The World Health Organisation told the institute it needed to prepare for future diseases and to respond to a potential pandemic.

They did, so when reports of a new disease came in January, and when the genetic sequence arrived from China ten days later, Sarah was confident they could crack it.

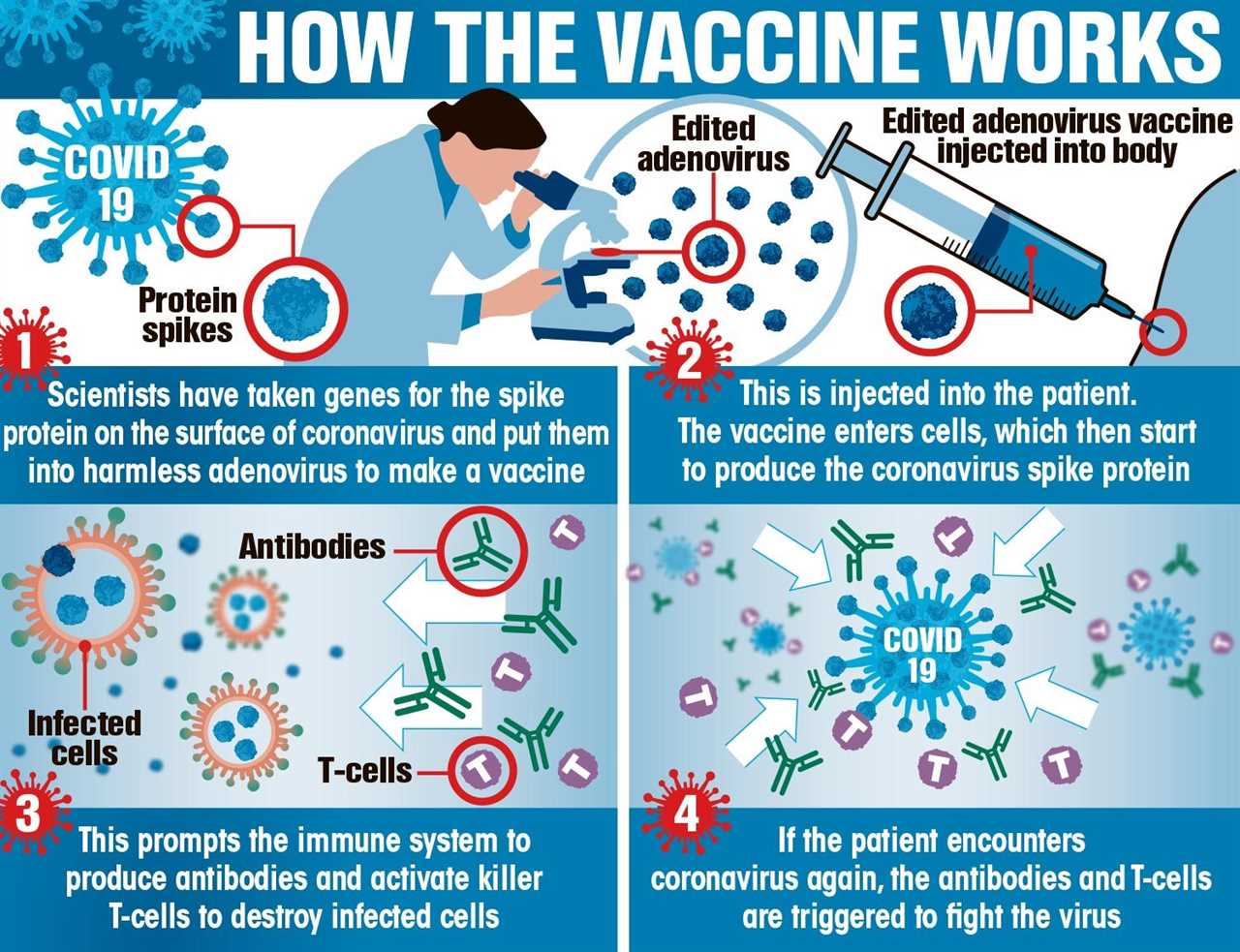

She said: “The prep work was already there. We’d worked on MERS, which is also a coronavirus, so all we did was repeat the stages and instead add the genetic code for the spike protein from this coronavirus to make it.

“At every stage we saw what we expected. We didn’t get to testing efficacy on MERS but we knew it was safe and created an immune response.

“This vaccine isn’t rushed — we’ve effectively been making it for a decade.”

Sarah, who worked 15 hours a day, read detective fiction at night to “chill out” and is looking forward to some long walks.

She was not allowed to volunteer for the clinical trials but her science student triplets, aged 21, did.

It can take a year for vaccines to be regulated by the Government’s Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency but data has been passed to them during the project to speed up the process.

Sarah added: “More than 20,000 people have been involved in trials. A vaccine can typically apply to be marketed after 5,000.”

She believes Covid-19 will remain “seasonal” and thinks we will face a future pandemic, probably from a virus found in birds or bats, but she insists: “We’re prepared. We can do it again.”

She adds: “I created the Covid-19 vaccine — it’s the pinnacle of my career. I did get emotional on Monday morning. My computer wouldn’t work, everything was going wrong.

“Then I pulled myself together and we had a Zoom call with Prince William, which was just wonderful!”

Another on the project was principal investigator Maheshi Ramasamy.

She is also a consultant physician who treated patients when Covid first hit.

She said: “It was terrifying. You’re used to being the expert but people were dying. We didn’t know how to treat them.

“As a physician, I’m used to patients sometimes dying but usually we could give them a ‘good’ death, with symptoms well controlled and their families around them.

“This was different. I couldn’t sit on their bed, or hold their hands and they couldn’t see our faces. Their families weren’t allowed in.

“You can’t lose it at work. I’d get home to my husband, an oncologist, who understood and just cry.”

Maheshi, who has children aged ten, 13 and 15, was involved in writing the protocol for the trial’s conduct and recruiting and screening volunteers.

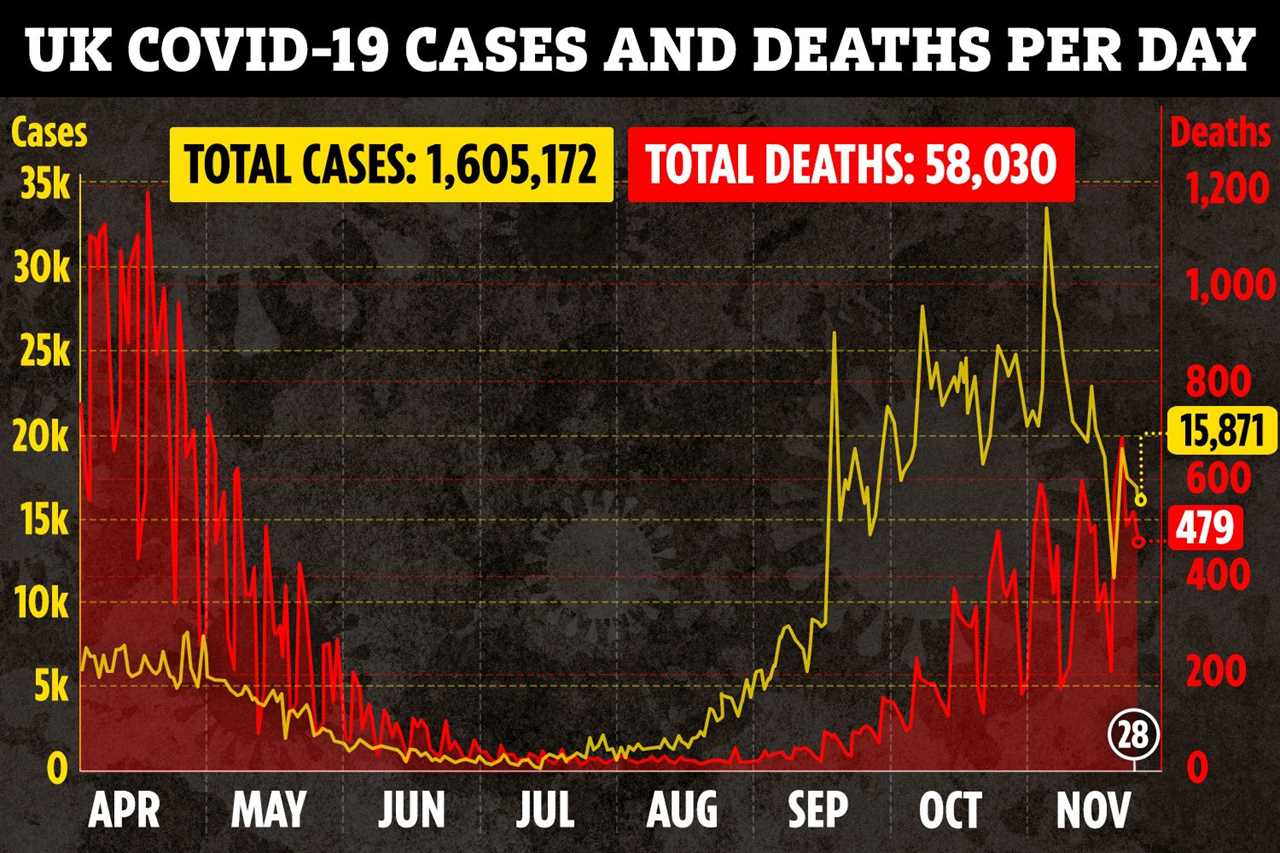

The results showed an overall efficacy of 70 per cent, a lower one of 62 per cent and a higher of 90 per cent — because different doses of the vaccine were used in the trial.

Some volunteers were given shots half the planned strength. Yet that “wrong” dose might end up as being crucial.

Maheshi added: “We know that 90 per cent were protected from getting ill when they were given a smaller, then a larger dose.

“Now we are looking at why. There are antibody immune responses in every age group and that older adults mount similar responses to younger adults.”

The NHS is preparing to administer the vaccine next month. It has side effects similar to the flu vaccine — a sore arm, tiredness, muscle ache and flu-like symptoms — but those over-70 suffer fewer of them.

Maheshi said: “You don’t think about saving the world, you are focused on the task in hand.

“This Christmas, I’ll be on the wards. It will be tough, but this time we understand better how to treat people. We’ve done it before and we will get through it again, together.”