THE Delta Covid variant first seen in India is now dominant in the UK.

A delay of lockdown lifting in England is on the cards, leaving millions with questions about why.

Read our coronavirus live blog for the latest updates

With such a hugely successful vaccine programme, why would a new Covid variant pose a threat?

The good news is, vaccines will go a long way to reduce the impact of the Delta variant.

Fully vaccinated people can still catch Covid, but they have a decent level of protection against disease caused by the Delta variant.

But those with only one dose of the jab have only around a 33 per cent protection against Delta – although the risk of severe disease or hospitalisation is much reduced.

And those with no jab – the large majority of under 30s – have zero immunity against it.

Fears more cases would lead to hospitalisations, putting pressure on the NHS, as well as cases of long Covid lead Boris Johnson to delay June 21’s Freedom Day.

So what do we know about the Delta variant?

What are the symptoms?

There is no evidence that symptoms of B.1.617.2 are any different to the original ones, including a new, persistent cough, high temperature and loss of taste and smell.

People who have received one or two doses of a vaccine have been warned they may show very little or zero symptoms as the jab appears to make infection more mild.

There is now evidence Delta causes more severe disease, according to PHE, doubling the rate of hospitalistion.

Figures for England showed a “significantly increased risk of hospitalisation” for people with the Delta variant, of 161 per cent.

People were also 67 per cent more likely to attend A&E.

Stats for Scotland – which has seen a surge in cases driven by the Delta variant – show a similar picture.

Experts say parents should look out for the following symptoms in their kids:

- Fatigue

- Headache

- Fever

- Sore throat/runny nose

- Loss of appetite

Adults are seeing different symptoms to the classic Covid set. Instead experts are reporting a headache, sore throat and runny nose for the under 40s.

The over 40s are more often experiencing headaches, runny nose and sneezing.

Who is most affected?

Cases are predominantly in younger people who are unvaccinated.

People being hospitalised are also younger than previous waves, meaning they are “less in need of critical care”.

It’s reassuring, however makes the case for jabbing all those under 30 before the lockdown lifts stronger.

Prof Andrew Pollard, of the Oxford Vaccine Group who led trials of the AstraZeneca vaccine, told BBC Radio 4’s Today Programme: “If you’re unvaccinated, then the virus will eventually find those individuals in the population who are unvaccinated.

“And of course if you’re over 50 and unvaccinated, you’re at much greater risk of severe disease.”

Experts have said “deprived, ethnic, urban communities may suffer disproportionately” from the Delta.

Uptake of the jab has been lowest among those of ethnic minority, and the coronavirus spreads faster in poorer and more crowded areas.

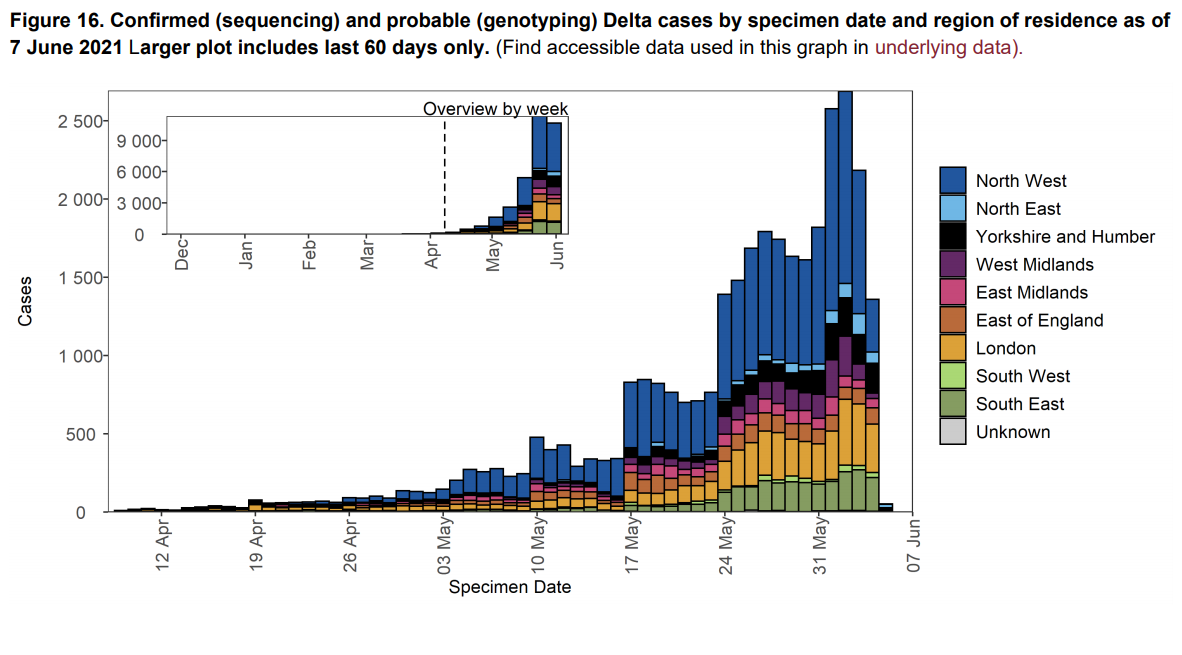

How many cases are there?

The latest data from Public Health England (PHE), on June 18, says there have been 76,000 cases caused by Delta so far.

It first emerged in the UK in mid-April.

Infections have risen by 80 per cent since PHE’s last update a week prior.

Delta now accounts for 99 per cent of new cases in the UK, PHE revealed.

It means the rapidly-spreading mutated virus has overtaken the Kent strain which forced England into the third national lockdown in January.

Maps have shown how rapidly the variant spread across England in a matter of weeks.

Where are cases highest?

Ever since Delta emerged, there have been areas that have suffered the most.

These are Bolton, Blackburn with Darwen and Bedford.

But the strain has since spread further out, affecting swathes of Greater Manchester and Lancashire.

After the North West region, London has been hardest hit – but not with cases anywhere near as high.

Although most regions in England have now got the Delta variant as the dominant virus – with shocking maps showing how fast it has spread.

Maps from the Wellcome Sanger Institute show the dramatic change in the picture over the past few weeks.

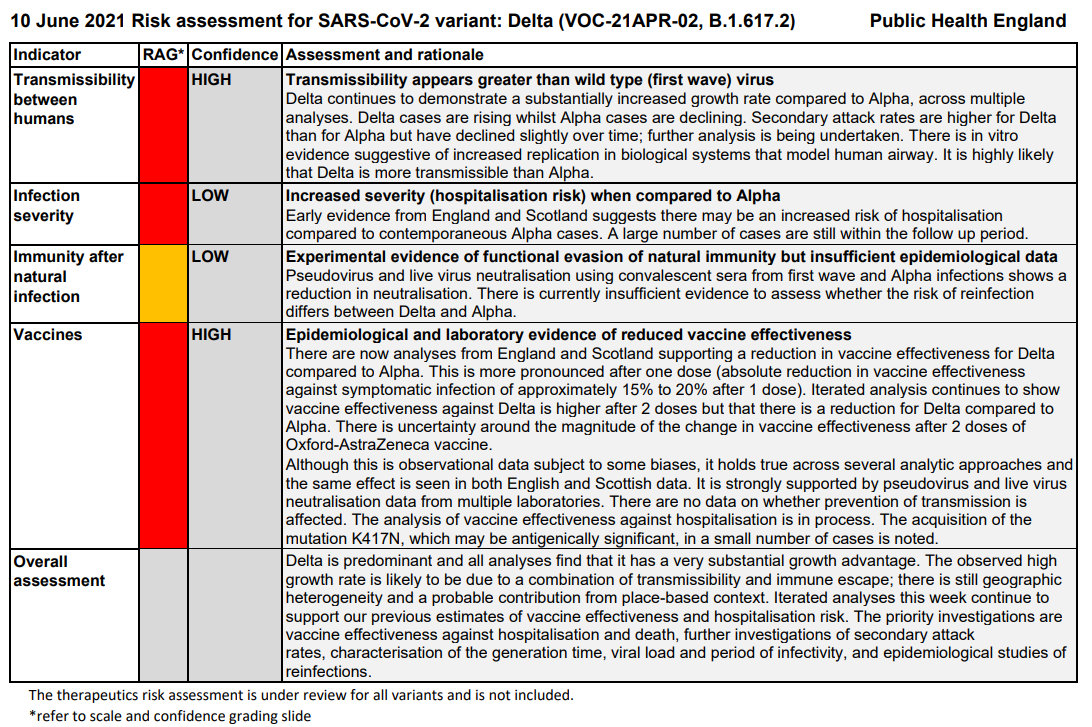

Why is the Delta variant a concern?

The strain is thought to be up to around 80 per cent more transmissible than the Alpha (Kent) strain.

The Alpha variant put England back into a third national lockdown because it spread so much faster than the original strain from Wuhan, China.

It looks like the doubling time for cases is less than a week, which is as bad as just before Christmas, according to one leading expert.

Therefore, the Delta variant threatens freedoms, even though the UK has a successful vaccination programme.

It could infect those who are unvaccinated – currently a quarter of the population – or vulnerable people who have not been able to get the jab or for whom the jab does not work for.

The strain also has the ability to dodge some immunity from vaccines.

This contributes to it being able to spread faster, as it can infect people even though they may have had a jab.

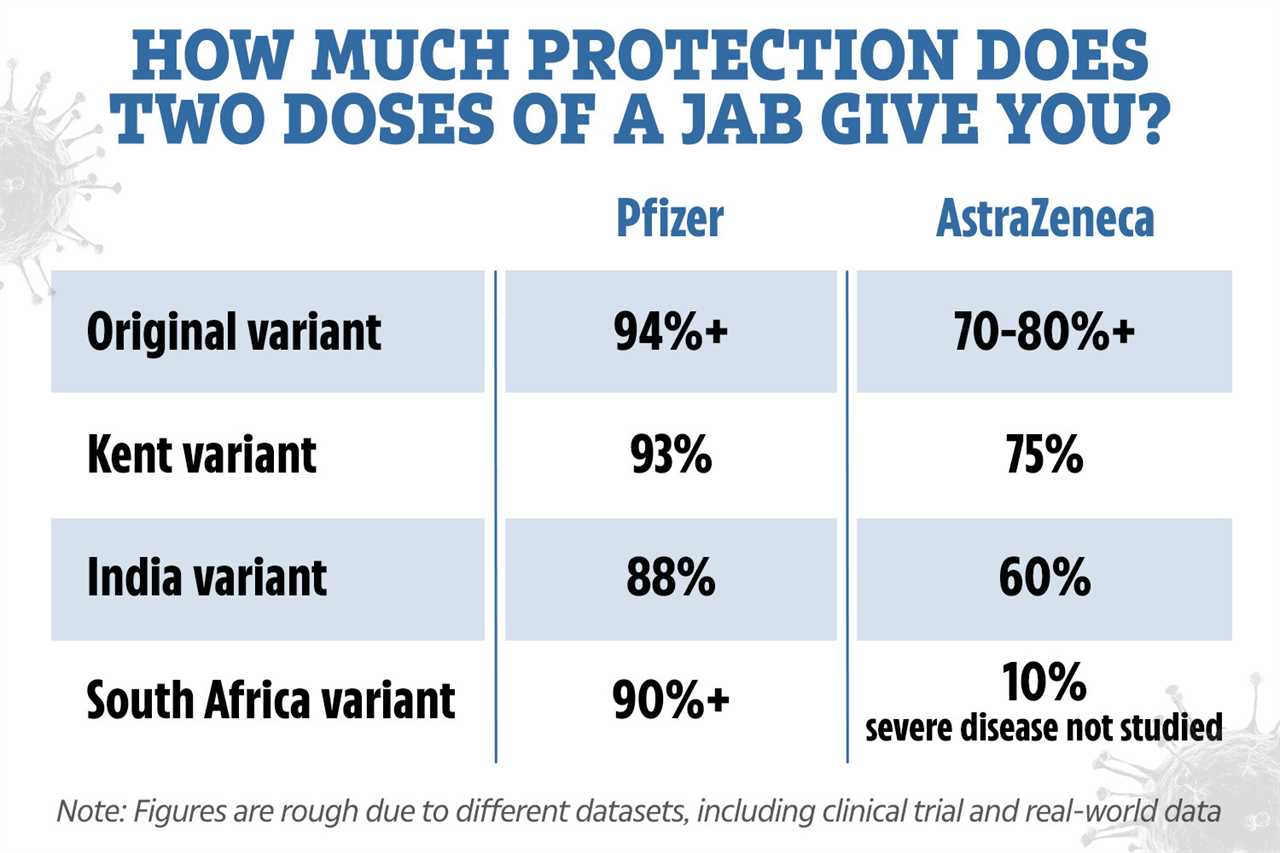

Will vaccines work against it?

Yes, but they are slightly weakened against it.

Data from PHE revealed one dose of either the Pfizer or AstraZeneca jab was 33 per cent effective against Covid disease from the Indian variant.

This compared to 50 per cent against the Kent strain, which had been dominant in the UK for several months.

Two doses of the Pfizer jab gave 88 per cent protection, while two doses of the AstraZeneca jab gave 60 per cent protection against the Indian strain.

But against the Kent strain, two doses of the jabs are 93 per cent and 66 per cent effective, respectively.

PHE’s risk assessment of the Indian variant’s ability to weaken vaccine efficacy had escalated to “high” on the back of the data.

But the Health Secretary Matt Hancock described the findings as “groundbreaking”.

He said “we can now be confident” that more than one in three fully jabbed brits have “significant protection” against the Indian variant.

Scientists said the key message was that it was imperative people got two doses of the jab when invited to protect themselves against the Indian variant.

Professor Ravi Gupta, a member of the Nervtag group advising the Government, said “a single dose is not particularly protective” against the Indian variant.

Will local lockdowns be used?

There were no plans to return to last year’s regional tiered approach to coronavirus restrictions, Communities Secretary Robert Jenrick said this week.

However, the PM said on May 13: “There may be things that we have to do locally and we will not hesitate to do them if that is the advice we get.”

Already millions of people have been told to be more cautious.

Six million people – one tenth of the UK’s population – in Greater Manchester and Lancashire were told to “minimise” travel in and out of the areas, which have been hit with a spike in cases.

Scotland then banned travel from Greater Manchester, with more areas – Birmingham, Blackpool, Cheshire East, Cheshire West and Chester, Liverpool City Region and Warrington – told not to leave their area.

Under the new rules people are urged to meet outside rather than at home and to keep two metres apart from those outside their household.

What is being done to slow the spread?

Targetted measures have been used in areas where the Delta variant is spreading at a worrying rate.

This includes surge testing and campaigns to encourage people to get their jabs urgently if they are eligible, with new vaccination hubs being set up.

The package of measures has helped turn the tide in Bolton, which was the first Indian variant hotspot in the country.

After an explosion in cases it has now got the outbreak under control and is now seeing a steady drop in new infections.

Meanwhile, the gap between first and second jabs will be cut down to eight weeks from the original twelve.

This is to ensure the most vulnerable have the fullest protection as soon as possible to help avoid hospitalisations.

The PM said: “We will accelerate remaining second doses, especially for the clinically vulnerable, right across the country, to just eight weeks after the first date.

“And if you are in this group the NHS, will be in touch with you. We will also prioritise first jabs for anyone eligible who has not yet come forward.”

What are the other Indian variants?

There are in fact three variants that are from India that emerged in the UK around mid-April.

These are B.1.617, B.1.617.2 and B.1.617.3.

The first and third variants are only listed as “under investigation”, rather than “of concern” like B.1.617.2.

Although they have been shown to have “escape mutations”, they have not grown in cases very quickly.