A WISE newspaper editor once told me the mark of a good paper was that by the time you put it down, you’d learnt lots of stuff you didn’t know before you picked it up.

In the spirit of that, I’ve been wondering what we know at the end of 2020 that we didn’t know when it started.

Last January, what would have been your answer to the following question: What is it that will happen in the year ahead that will bring the whole world together in the same crisis, something ordinary folk from Sidmouth to Sydney and Sao Paulo to Shanghai will be united in battling?

I think I would have gone for a nuclear war, a huge meteor spotted heading towards us or the supervolcano beneath Yellow- stone National Park blowing its top.

It’s not been quite that bad, so far anyway. But neither has it been anyone’s idea of a picnic.

Looking back, there was an air of farce about the early days. At the end of January escapees from the eye of the coming storm, the Chinese city of Wuhan, were flown into RAF Brize Norton.

They were taken from there in buses to a hospital on the Wirral and essentially locked up. Bizarre. I hope somebody remembered to let them out.

We were always told this pandemic thing would befall us one day. I think we kind of assumed that by the time it happened we’d have invented the means to stop it in its tracks. As our Prime Minister might have put it, we’d send it packing.

Aids, the Sars virus, Ebola and malaria have all claimed countless lives but, for most of us in this country, never came knocking on our doors. Now we’ve had a taste of something that, one way or another, has knocked on all our doors.

Even as we watched it creep from China towards us and then wreak havoc in Italy, we still somehow didn’t think it would be so bad here. How wrong we were.

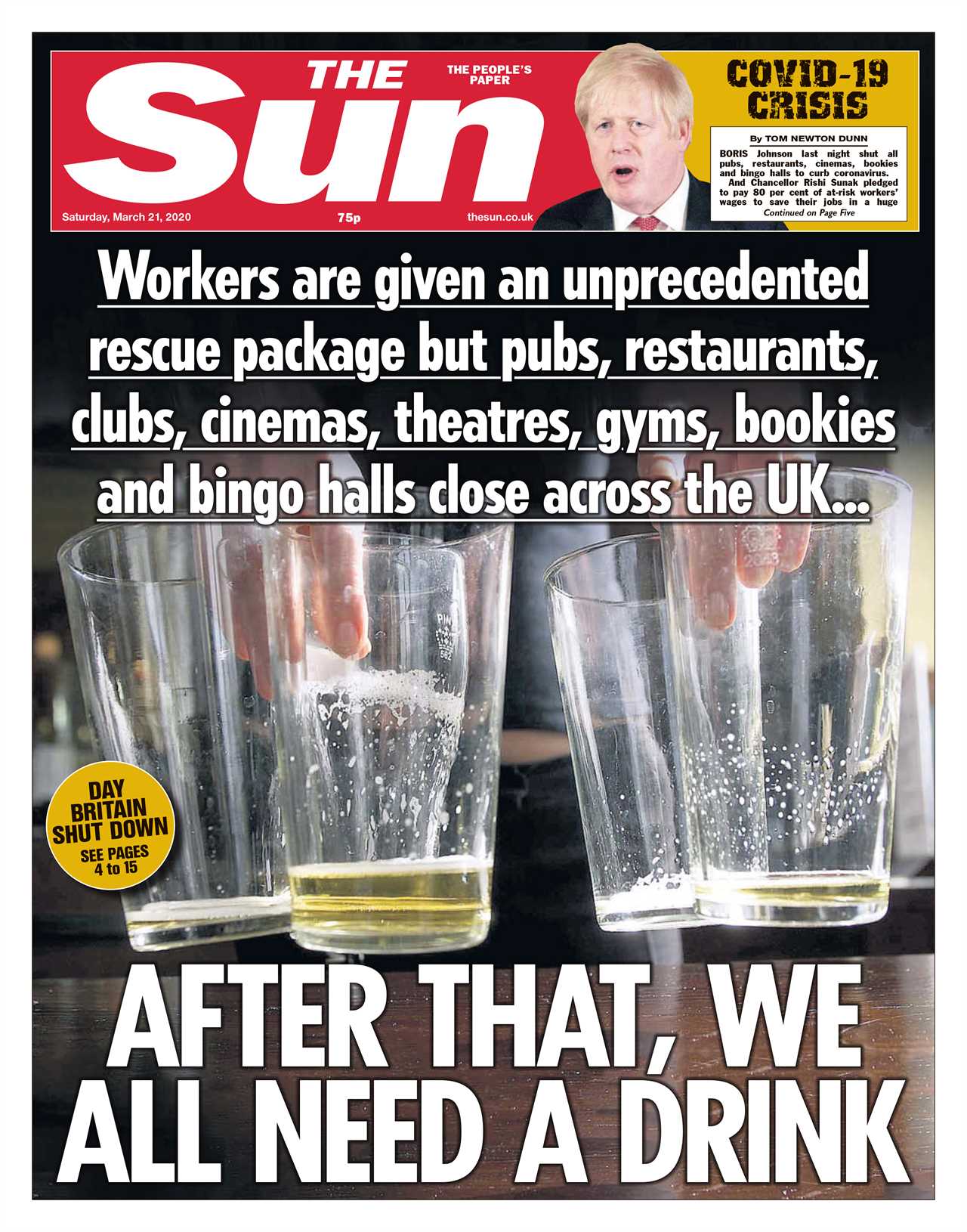

World War Flu, as a Sun headline had it, was with us. And this is the first lesson we’ve learnt: Count your blessings while you have them because occasionally the prophets of doom are bang on the money.

ROLLING AROUND

Before long, nothing else seemed to matter, everything seemed trivial. In early February I remember reading slack-jawed about Phillip Schofield coming out. The showbiz world turned on its axis. If he’d left it another couple of months, I doubt anyone would have batted an eyelid.

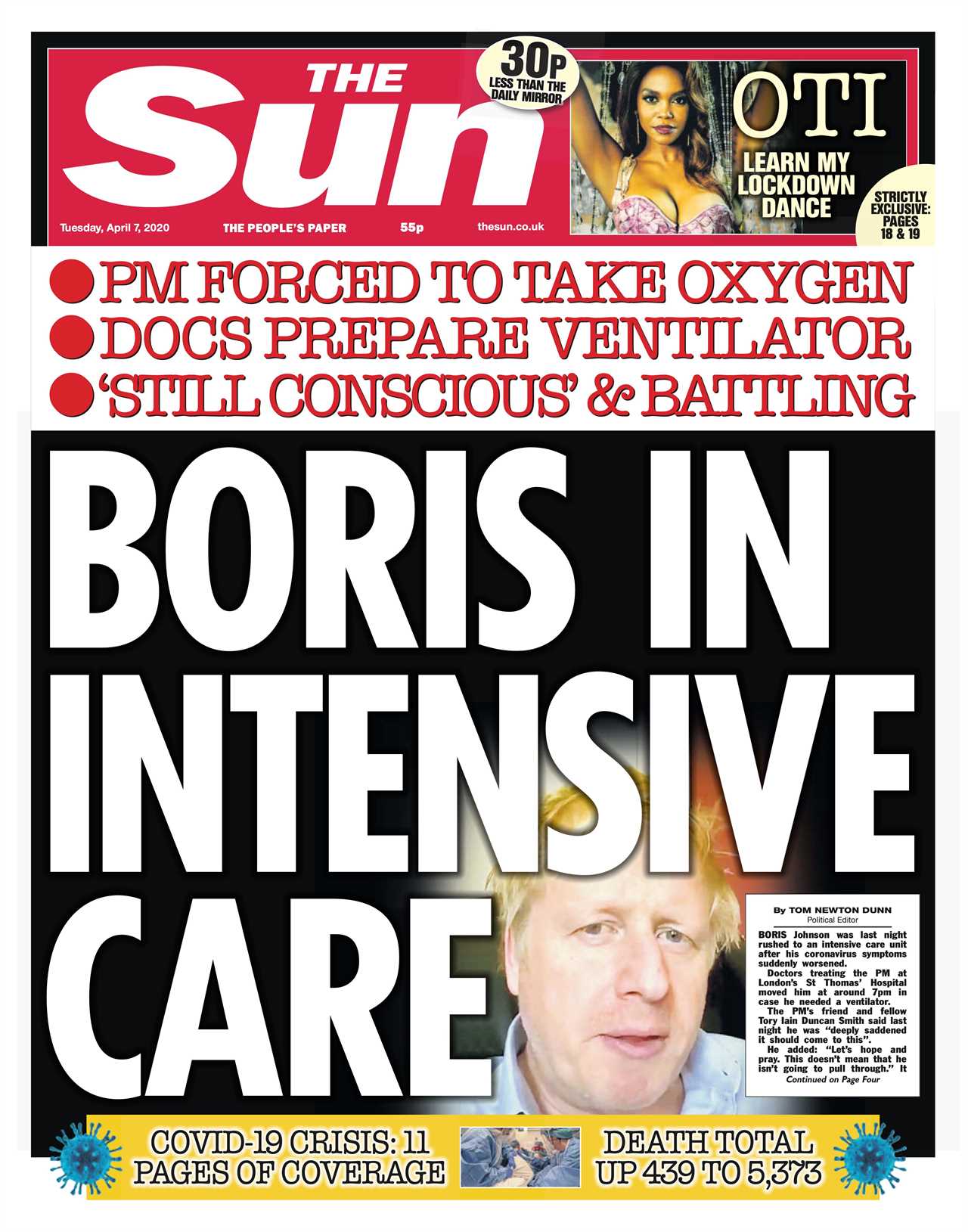

By then, for heaven’s sake, we were all confined to our homes, watching the news as our Prime Minister was in hospital fighting for his life. The man who’d warned that many of us would, “lose loved ones before their time”, nearly found himself among their number.

Thankfully, he made it. But now we knew that, as humans, we were all vulnerable, and flawed with it. The cleverest of us proved to have, on occasion, the brains of rocking horses.

Professor Neil Ferguson, the gloomiest of epidemiologists, implored us to behave ourselves but then turned out to be rolling around with a lover married to someone else.

The great political brain Dominic Cummings was caught clocking up hundreds of miles carting his family up and down the country, checking his eyesight as he went. The professor apologised for all he was worth, Mr Cummings not so much.

Somehow, the rest of us had to deal with our worlds closing in around us. Our four walls became as much of life as we could experience.

On the good days we could reflect that at least we had learnt how precious the small things were to us. Just the privilege of spending time with our friends and family, being at a football match, or in a cinema, or in a pub or club, or even a school or a college. These we had all taken for granted.

May we never do so again. Many of us missed the physical contact as even handshakes were ill-advised.

Touching elbows became the norm, a practise which I found absurd until it too was essentially banned.

And so it was that within weeks of scorning this stupid elbow business, I was actually missing it, thinking of what I wouldn’t give for a rub of someone’s elbow.

Lockdown was much easier to bear for some than others. I was blessed to be able to actually enjoy aspects of it, so I winced when I saw the Oxford epidemiologist Professor Sunetra Gupta describe lockdown as “a middle-class luxury”.

And I read someone else describe it as a time when people who could afford to do so stayed at home, while those who couldn’t brought things to them.

Yes, hard-working people using bikes, mopeds and vans saw that our needs were catered for, and that the shops we were allowed to visit were stocked with what we went there for.

And this all taught us who the essential workers really are.

Laughably, as a journalist, I was classed as one. How absurd. It goes without saying that the doctors, nurses, paramedics and care workers are critically important, but no less so are the legions of fetchers and carriers and fixers without whom the cogs of this country grind to a halt.

Next time I hear someone disparage the notion of “white van man”, I’ll be minded to throw them under one.

However bad things got, we learnt we have the capacity to just get on with it. By way of relief we managed to lose ourselves in other worlds. To misquote Churchill, never have so many box sets been watched so much by so many of us.

Football returned, and we even managed to deal with watching it played in empty grounds — although, to be fair, by year’s end we’ve had enough of that.

WHOLE LOT BETTER

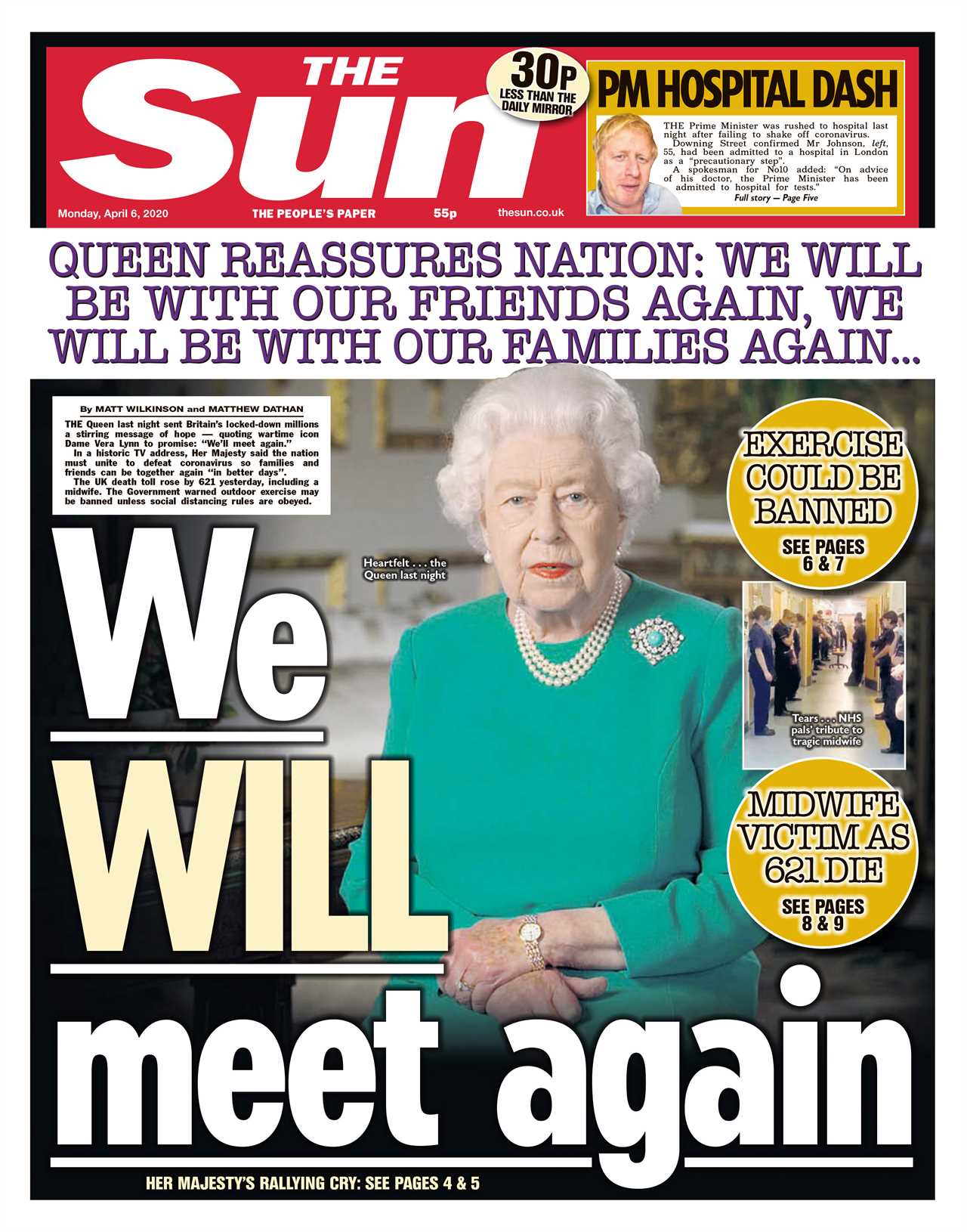

Not for the first time, we were reminded why we need the royals. Setting aside Harry and Meghan for a moment — and they’re supposedly ex-royals after all — William and Kate showed us how it should be done. They’ve always been there, supportive and compassionate.

As for the Queen, you’d need a heart of stone for it not to melt during her Christmas message. To use language Her Majesty might not recognise, she nailed it.

We learnt two things about rules this year: That we hate them and that we need them. I’m caught between several stools here, veering wildly between thinking the rules are too lax and too strict and too randomly applied. I rise to fury when I see someone breaching a rule yet am often wild with indignation if someone dares to suggest I’m doing something risky.

All we know for sure is that if there are too many rules, which change all the time, you end up with no rules at all. And the more you have, the more you get drawn into wrestling with absurd questions like what exactly constitutes a substantial meal.

Never has the scotch egg industry had it so good. My favourite line on this I saw chalked on a board outside a pub in Liverpool: “Soup Of The Day — Carling £2.40.”

Through all this we kept smiling. I was in the Budgens at my local garage one Sunday morning in spring, when it was all dark moods in the brightest of sunshine. One of the staff was at the door dispensing compulsory hand sanitiser. With degrees of grumpiness and gratitude, we complied.

When a huge, angry-looking bloke came to glower his way through the door I feared for the sanitiser man, who was obviously fearing for himself too.

The big guy eyed him for a menacing moment, during which time everyone in this Budgens seemed to fall silent. Then he grinned, held his hand out and said: “Go on then, pal, I’ll have some off you. Haven’t done one for five minutes.” And everyone laughed.

Everyone laughed because we knew we were all in it together, everywhere.

Think about it: Never in human history has everyone in the world been in the same boat. Never before would we have been able to look any one of the world’s other eight billion people in the eye and say: “I know something of what you’re going through.”

It’s a special feeling, and it’s almost a privilege to have lived through it. And now that we’re in the darkest hour before the dawn, when the vaccines will save us, we can be sure of one thing: That 2021 will end up being a whole lot better than 2020.

Before long, it will be definitely be a happier New Year.