Two months ago, Republicans in Georgia won more votes for Senate than the Democratic candidates, even as Joe Biden defeated President Trump at the top of the ticket. On Tuesday for the runoff races, the Georgia electorate was very different; so was the outcome.

Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock prevailed in Georgia with the help of superior Democratic turnout, especially among Black Georgians, which allowed them to overcome their disadvantage with voters who might have been decisive in Mr. Biden’s victory but voted Republican down-ballot.

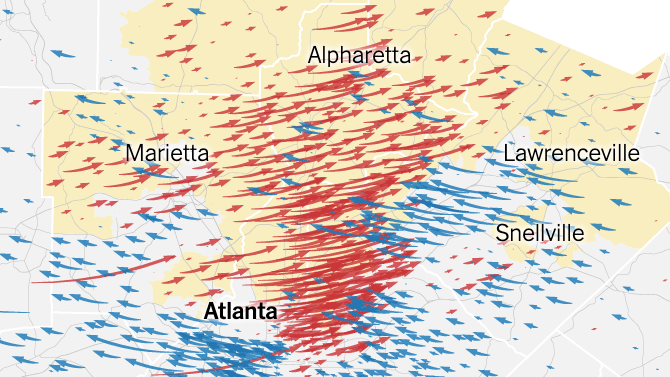

An authoritative analysis of the results won’t be possible until the state releases detailed data on exactly who voted and who stayed home. But the data available so far shows that Democrats benefited from a more favorable electorate, as a greater proportion of Democrats and especially Black voters returned to the polls than Republicans and white voters without college degrees. (The accompanying map shows how the margins shifted for Mr. Ossoff in his race against David Perdue; the map for Mr. Warnock vs. Kelly Loeffler, not shown, is essentially the same.)

Over all, turnout reached a remarkable 92 percent of 2020 general-election levels in precincts carried by Mr. Biden in November, compared with 88 percent of general election-levels in the precincts carried by Mr. Trump. These tallies include Upshot estimates of the remaining uncounted vote by precinct, and it suggests that nearly all of the Democratic gains since the November election can be attributed to the relatively stronger Democratic turnout.

A majority of Georgia’s Democratic voters are Black — they are roughly 30 percent of the overall electorate — and it was these voters who drove the stronger Democratic turnout. Over all, turnout reached 93 percent of 2020 levels in precincts where Black voters represented at least 80 percent of the electorate. In comparison, turnout fell to 87 percent of general election- levels in white working-class precincts.

In any election, it can be hard to decide whether to frame the result as a strong turnout for one side as opposed to a weak one from the other. In this election, it is easier to argue that the Black and Democratic turnout was strong rather than to say that the Republican turnout was weak. Republican turnout was extremely strong for a runoff election; had analysts been told of G.O.P. turnout in advance, most would have assumed the Republicans were on track to win.

The relatively strong Democratic turnout produced such a marked shift in part because the November election featured relatively weak Black turnout. In the November election, the Black share of the Georgia electorate appeared to fall to its lowest level since 2006; Black turnout, though it increased, did so to a lesser degree than non-Black turnout. In part for this reason, Democrats had legitimate cause to hope they could enjoy a more favorable electorate in the runoff than in the general, even though they have tended to fare worse in Georgia runoffs over the last two decades.

It will be some time before the Black share of the runoff electorate can be nailed down with precision, but the results by precinct and early voting data suggest it may rise two points higher than in the general election, to a level not seen in the state since Barack Obama’s re-election bid in 2012.

As a result, Democratic gains were concentrated in the relatively Black and Democratic areas where superior Democratic turnout overwhelmed Republican support.

Democrats made their largest gains in the predominantly Black counties of the so-called Black Belt — a region named for its fertile soil but now associated with the voters whose ancestors were enslaved to till it — as well as the growing majority-Black suburbs south of Atlanta.

Democrats also made gains in the state’s small number of majority-Hispanic areas. Turnout fell to a far greater extent in these precincts than they did elsewhere in the state. The Democratic gains in these precincts might have been because a decline in Hispanic turnout increased the Black share of the electorate in relatively diverse but predominantly Hispanic precincts, or because the Latino voters who stayed home were relatively likely to back Republicans in November.

At the same time, the relatively limited Democratic gains in Republican areas suggest that there was virtually no shift in voter preference since the November election, despite hundreds of millions of dollars in television advertisements.

Democrats had cause for hope they might change some minds. Mr. Biden had run ahead of the Democratic Senate candidates in November, and they sought to lure some of these voters to their side — especially after the president’s effort to foment doubts about the outcome of the November election. Instead, Republican candidates fared even better in affluent precincts — those with a median income over $80,000 per year — than they did in the general election, and in the precincts where Republican candidates ran farthest ahead of Mr. Trump in November.

It is hard to tell whether any Republican gains in these precincts can be explained by underlying shifts in turnout or an intentional shift to ensure divided government. If there is any silver lining for Republicans in the election, it is the possibility that these voters — who are decisive in many competitive congressional districts even if not always in statewide elections — may be inclined to serve as a check against the Democrats in the midterms, as has often been the case in recent political history.

For now, it won’t be much consolation.