WASHINGTON — The top Democrats in Congress on Wednesday endorsed a bipartisan $908 billion stimulus compromise as a baseline for talks, offering a significant concession in an effort to pressure Republicans to revive stalled talks on providing additional relief before the end of the year.

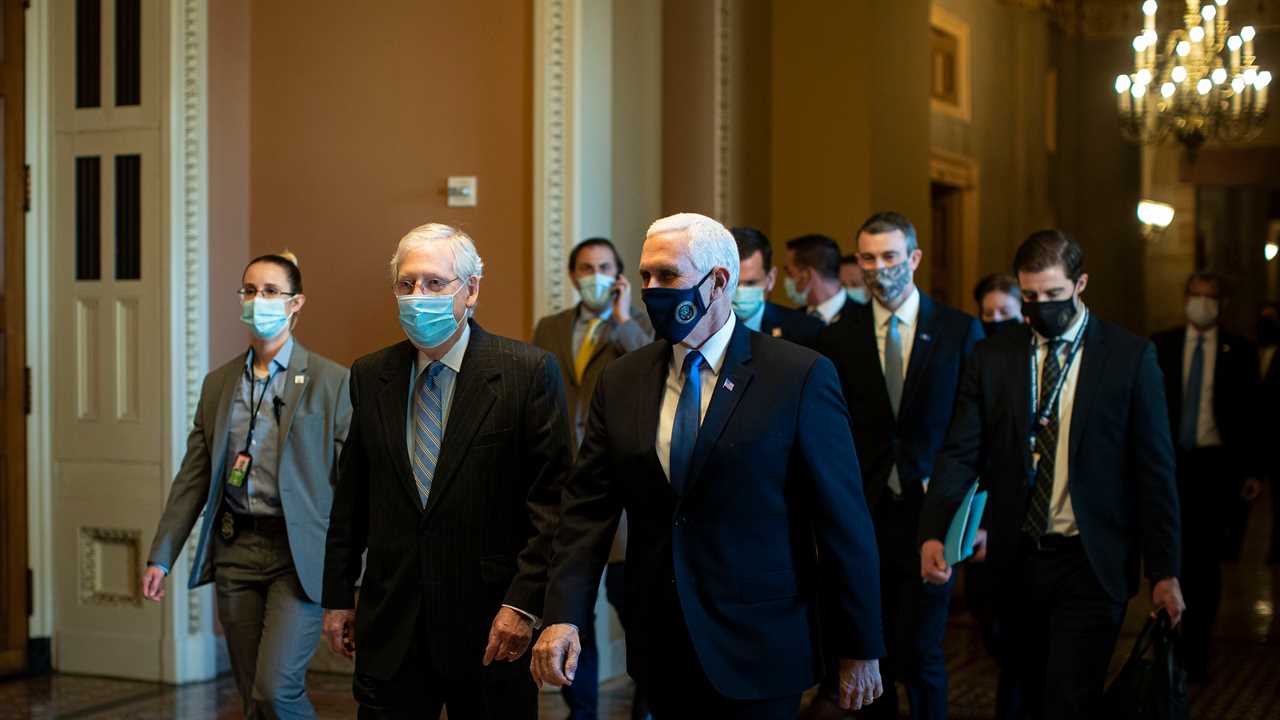

After months of publicly insisting that another stimulus package must provide at least $2 trillion, Speaker Nancy Pelosi of California and Senator Chuck Schumer of New York, the Democratic leader, called on Senator Mitch McConnell, Republican of Kentucky and the majority leader, to return to the negotiating table with a bill less than half that size as a starting point.

President-elect Joseph R. Biden Jr., whose advisers had pushed privately in recent weeks for lawmakers to make compromises to pass an economic aid agreement as quickly as possible, also offered a blessing of sorts for the effort. In a virtual event with laid-off workers and a small-business owner struggling amid the pandemic, Mr. Biden said the bipartisan package “wouldn’t be the answer, but it would be immediate help for a lot of things, quickly.”

The measure, spearheaded by Senator Joe Manchin III, Democrat of West Virginia, and Senator Susan Collins, Republican of Maine, would restore lapsed federal jobless benefits, providing $300 a week for 18 weeks; would include $288 billion for struggling small businesses, restaurants and theaters and $160 billion for fiscally strapped cities and states; and would create a temporary liability shield for businesses operating amid the pandemic.

The Democratic decision to publicly embrace it offered no guarantee of a swift deal with Mr. McConnell, who on Tuesday began circulating a significantly smaller framework with the promise of a presidential signature. Should talks resume, it also remains unclear how hard Democrats would push to expand the size of the package.

The two sides would need to bridge big differences on the details, including two particularly thorny issues: whether to send federal money to state and local governments to help patch budgetary holes opened by the recession, which many Republicans oppose at any dollar amount, and how to limit the legal liability for businesses opened during the pandemic, an effort many Democrats have criticized.

“Of course, we and others will offer improvements, but the need to act is immediate, and we believe that with good-faith negotiations, we could come to an agreement,” Ms. Pelosi and Mr. Schumer said in their statement. The pair had sent a new offer of their own on Monday evening to Mr. McConnell and to Representative Kevin McCarthy of California, the Republican leader, but after a group of moderate senators in both parties presented a plan on Tuesday, Ms. Pelosi and Mr. Schumer threw their weight behind the framework “in the spirit of compromise.”

It amounted to a noteworthy admission by Democrats that they could no longer hold out for the sweeping $2.4 trillion package that they had demanded, particularly as coronavirus cases rise across the country and calls for relief continue to mount. For months, Republicans have blamed Democratic leaders for insisting on the expansive plan and blocking smaller pieces of aid — like new loans for small businesses — from advancing.

Democrats have accused Mr. McConnell of blocking an agreement and failing to compromise. Their move on Wednesday was in part an effort to dare him to enter compromise talks, and Democrats could use stalled negotiations as a rallying cry in two runoff elections in Georgia next month that will determine control of the Senate in 2021.

But it was also a bid to find some sort of agreement to bolster the economy that could be enacted before Mr. Biden takes office.

The shift in demands came after Mr. Biden said on Tuesday that any stimulus legislation passed during the lame-duck session “is lucky to be, at best, just a start” and that Congress should act in the coming days. Ms. Pelosi and Mr. Schumer, in their statement, also pointed to the imminent distribution of a vaccine and the federal funds that will be required to safely disperse the first rounds of it across the country.

The compromise plan, drafted by a bipartisan group that included Senators Mark Warner, Democrat of Virginia; Mitt Romney, Republican of Utah; and Angus King, independent of Maine, is intended to serve as a stopgap measure through March. It was endorsed by the bipartisan House Problem Solvers Caucus, whose members and staff consulted on it with some senators after unveiling a similar bipartisan proposal.

Mr. Manchin said the group hoped to have text ready as early as Monday.

“In these past 24 hours, there’s been a lot of socializing of the ideas,” said Senator Lisa Murkowski, Republican of Alaska, adding that she and other senators involved in the framework had broken off into groups to hammer out individual issues. “We’ve been all kind of working with colleagues on the floor saying: ‘Yeah, this is what we’re talking about. Is this something you can get behind?’”

Mr. McConnell appeared to pan the bipartisan framework on Tuesday, repeatedly reiterating that President Trump’s support would be needed for any coronavirus deal. And speaking to reporters on Capitol Hill, Steven Mnuchin, the Treasury secretary, declined to weigh in on the bipartisan measure or the offer put forward by Ms. Pelosi and Mr. Schumer, instead reiterating that Mr. Trump would sign Mr. McConnell’s plan.

But some lawmakers indicated that they would be open to supporting the bipartisan framework, even if it crept closer to $1 trillion than some of their colleagues would have liked. The effort received additional support on Wednesday from the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the influential business lobbying group in Washington, which said in a statement that it “strongly supports the bipartisan group of lawmakers who have put forward a new pandemic relief package” for the lame-duck session.

“There are message bills, and there are bills that can pass,” Mr. Romney said on Wednesday before Democrats announced their support for the plan. “Our bill that we’ve been working on is one that has support both sides of the aisle sufficient, I believe, ultimately to pass.”

Senator John Thune of South Dakota, the No. 2 Senate Republican, suggested to reporters that “maybe we can merge” the bipartisan framework with Mr. McConnell’s outline and that the group of senators “has had a lot of success in winnowing the list of issues.”

Mr. Biden said on Wednesday that he had been “urging our congressional Republicans to work on a bipartisan emergency package now,” though he stressed that such a package, “at best, is only going to be a down payment.”

He also said that his transition team was already drafting legislation to help bolster the economy, which he would push Congress to approve upon taking office.

“To state the obvious,” Mr. Biden told a woman who lost her job in the pandemic, “my ability to get you help immediately does not exist.”

“We’re going to get through this. You’re going to get through this,” he added. “It’s going to be hard as hell for the next 50 to 70 days, unless the House acts in some way, the Senate acts and passes some kind of material.”