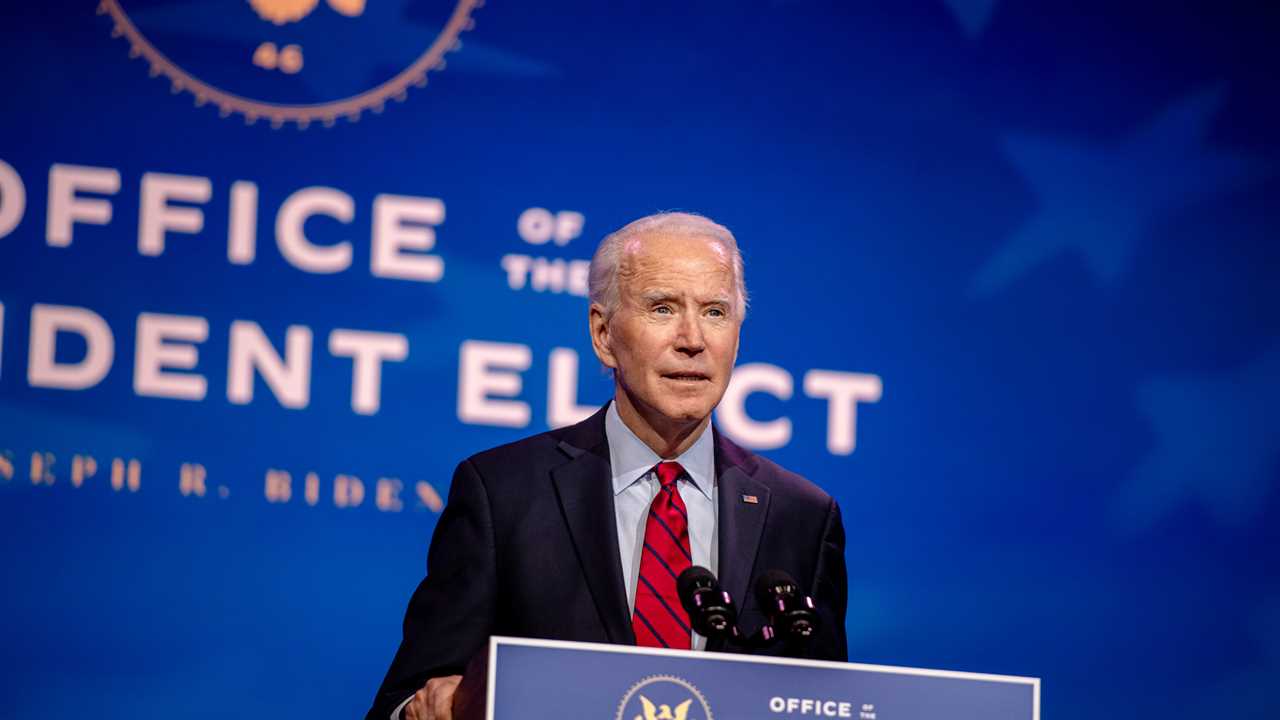

Joseph R. Biden Jr. has already won the presidential election, but on Tuesday he moved one step closer to the White House.

By the end of the day, the nation was set to reach the so-called safe harbor deadline, which is generally accepted as the date by which all state-level election challenges — such as recounts and audits — are supposed to be completed.

Broadly, that means that President Trump’s efforts to overturn the presidential election are nearing the end of the line. After Tuesday, state courts would most likely have to throw out any new lawsuit challenging the election.

That’s because election results that have been certified by the states are now considered conclusive, and by law those states’ Electoral College votes must be counted by Congress. By late Monday, every state but Hawaii had certified its results, and Mr. Biden had secured more than the 270 electoral votes needed to become president.

The safe harbor deadline would normally pass without much notice, but it feels especially notable this year as Mr. Trump and his allies try to subvert the election process. Here are more questions and answers about the deadline:

Where did the safe harbor deadline come from?

A relatively obscure passage of the Electoral Count Act of 1887 says that if there are disputes in a state over the results of an election, but the results are settled “at least six days before the time fixed for the meeting of electors,” those results are conclusive and must be counted by Congress.

That’s what is known as the safe harbor deadline. Federal law says the Electoral College must vote on the Monday after the second Wednesday in December — this year, Dec. 14. The safe harbor deadline falls six days before that, on Dec. 8.

What are the practical implications of the deadline?

It essentially acts as a guarantee that Congress must count the Electoral College votes of states that have certified their elections and signed off on a slate of electors.

In states that have certified their results, the deadline should also help insulate against further legal challenges in state courts.

“It plays into litigation because courts are aware of this deadline and want to give the states this benefit, so they do their best to try to comply with it,” said Richard L. Hasen, an election law expert at the University of California, Irvine.

How do states qualify for safe harbor?

The deadline is traditionally considered met when a state certifies its votes.

The certification processes vary from state to state, but all require the governor to compile the certified results and send them to Congress, along with the names of the state’s Electoral College delegates.

President Trump has urged Republican-controlled legislatures in key states to step in and choose their own slates of electors, but he has been rebuffed at every turn. In the unlikely event that a state legislature attempted to name a separate set of electors, the U.S. House and Senate would need to agree to accept those electoral votes when Congress meets to count the votes on Jan. 6.

Does this mean the end of lawsuits from Trump and his allies?

Not really. But their odds of success are getting even longer. The Supreme Court on Tuesday rejected a request from Pennsylvania Republicans to overturn the state’s election results.

Currently, there are only a few state-level lawsuits left unresolved, including some in Georgia, Arizona, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania.

One open question is whether federal lawsuits can continue after the safe harbor deadline, though it is likely that they can and will. Even so, there are now only three federal lawsuits remaining — two in Wisconsin and one in Arizona — and they will almost certainly wrap up soon.

Regardless, the Trump campaign and its allies have not shown that they will be deterred from filing more election-related lawsuits, even though they have lost nearly 50 cases.

Has safe harbor come into play before?

The Supreme Court majority in Bush v. Gore, the 5-to-4 decision in 2000 that handed the presidency to George W. Bush, cited the safe harbor provision as a reason to move quickly in wrapping up the election.

On Tuesday, lawyers for the Trump campaign downplayed the significance of the deadline in a news release, saying that “it is not unprecedented for election contests to last well beyond December 8.”

“Justice Ginsburg recognized in Bush v. Gore that the date of ‘ultimate significance’ is January 6, when Congress counts and certifies the votes of the Electoral College,” the release said. “The only fixed day in the U.S. Constitution is the inauguration of the president on January 20 at noon.”

But Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg was in dissent in Bush v. Gore.

Adam Liptak contributed reporting.