Thousands of Texans have had their absentee ballot applications denied as a result of regulations put in place under the state’s new election law, a jump in rejections that could force many older and disabled voters to either vote in person or not at all in primary elections early next month.

With a Friday deadline, election officials in the state’s most populous counties have rejected 10 percent — or 12,000 — of the absentee ballot applications received as of Thursday, according to voting data obtained by The New York Times. Officials said the rejection rate reflected a significant increase from past years, and most often because a voter failed to satisfy the new identification requirements.

“It’s high, there’s no question,” Bruce Sherbet, the election administrator for Collin County, northeast of Dallas, said of the number of rejections. Mr. Sherbet said his county typically rejects a handful of applications. This year, that number was roughly 300.

The Times tallied rejected applications in 12 of the 13 Texas counties with more than 400,000 residents. Bexar County, home to San Antonio, did not disclose its numbers. The total of rejected ballots could still change as applications were still arriving ahead of the Friday night deadline.

The figures are the broadest look yet at the impact of the voting law passed in August by the Republican-led legislature in an attempt to tighten procedures and, supporters of the law argued, to restore voter confidence in the election process.

As they prepare for the March 1 primary, election officials say the new law is sowing confusion among voters and further burdening already taxed local election offices.

As one of 18 states to pass more restrictive voting laws after the 2020 presidential election, Texas’ rocky rollout could provide a preview of what could come elsewhere

Confusion over absentee ballot applications has a more limited impact in Texas than in many other states, however. Texas only allows voters who are over 65 or who have a verified disability to vote by mail. During the 2020 election, more than 1 million Texans voted by mail, although that number is expected to fall, as turnout regularly dips in the midterm elections.

There are signs that the problems, particularly with new identification rules, may extend beyond applications to processing ballots. With less than a week of data on returned ballots, Harris County said its ballot rejection rates were as high as 34 percent, and Dallas County had rejected about 20 percent of ballots.

“We’re seeing an alarming number of mail ballots being rejected and local officials are left scrambling to protect voter access as the deadline looms,” Isabel Longoria, the elections administrator of Harris County, said in a statement.

The new law, a key Republican priority after former President Donald J. Trump claimed there was widespread fraud in the 2020 election, added a host of new restrictions to voting in the state, including banning drive-through voting and 24-hour voting, limiting drop boxes, adding new identification requirements to absentee ballots and preventing local election officials from promoting absentee voting.

Republicans vowed that the law made it “easier to vote, harder to cheat.” But some voters in Texas have found the absentee process far from easy, even those who are highly motivated.

In Corpus Christi, Linda White, 72, has been voting by mail for several years with her husband Jack, 74. A Democrat, she said that she and her husband, a Republican, have had their applications rejected three times this year.

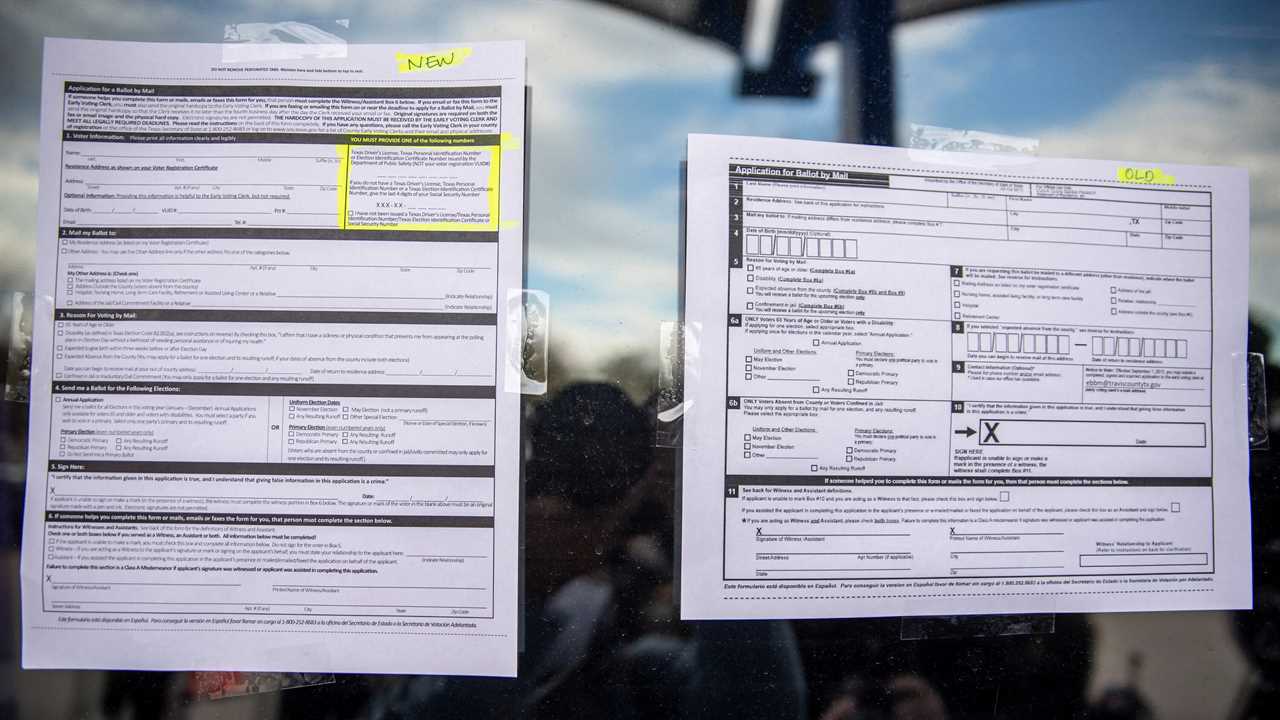

The first time, they inadvertently used an old form posted on the Texas secretary of state’s website (the form was updated in January). Then, they were rejected for overlooking the fields for both their driver’s license numbers and partial Social Security numbers. Finally, Ms. White printed out a new application, and she still did not see the required fields, so she hand-wrote both identification numbers on the side of her application.

That was rejected as well.

“If I hadn’t just been a determined, hardheaded old woman, and my husband just as determined and hardheaded, I think I would have given up after a couple of shots at this,” Ms. White said in an interview.

The new rules require voters to put either their Texas driver’s license number or the last four digits of their Social Security number on ballot applications. If voters omit something, or make an error in another field, they can correct their applications up to 11 days before an election.

Heidi Schoenfeld, a precinct chair in San Antonio who currently serves on the voter protection committee for her county’s Democratic Party, had her application for an absentee ballot rejected twice this year.

“We’ve been voters continuously for 53 years, we’ve been registered that long, and I’ve been following what we’re supposed to do,” said Ms. Schoenfeld. “And if we can’t get it right, there’s just something wrong.”

Some political campaigns and the state parties have stepped in to promote absentee voting, although one prominent candidate was found to be giving out incorrect information.

The re-election campaign of Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick, a Republican, instructed supporters to mail their ballot applications to the secretary of state instead of to county officials, a clear break with the rules that could have resulted in the rejection of every supporter who followed those instructions. The secretary of state said it forwarded the applications to the counties.

The Patrick campaign said the secretary of state was “trusted and respected” and wanted to “give voters an added layer of comfort,” Allen Blakemore, a campaign consultant for Mr. Patrick, wrote in an email to the Texas Tribune, which first reported on the Patrick campaign’s ballot applications.

The office of Gov. Greg Abbott, the Republican governor who made new election legislation a top priority, issued a statement placing some blame for the rise in ballot rejections on local election officials.

“Reports of high rejection rates of mail ballot applications at the county level are the result of election officials erroneously interpreting the law and going to the press instead of the Texas Secretary of State’s office for assistance,” said Nan Tolson, a spokeswoman for Mr. Abbott.

Sam Taylor, a spokesman for the Texas secretary of state, said that the office has been working since December to help educate voters and election officials on the coming changes. But Mr. Taylor allowed that the time crunch — the new law went into effect in December — was causing problems.

“It’s a lot to get used to in a very short amount of time,” he said.

Local election officials said they knew these problems would arise when the new law was passed last year.

“We anticipated this, we expressed it to the Legislature, but it went unheeded,” said Remi Garza, the top election official in Cameron County.

Some rejections stemmed from layering the requirements of the new law atop a byzantine electoral bureaucracy.

Following her first rejected application, Ms. Schoenfeld was told that the county election office did not have her driver’s license number on file, and that she would need to fill out a new voter registration form.

She filled a registration form and a new application and sent them back on the same day. Yet the two forms are handled in two different suites at the county election office, and the registration had not been processed before her ballot application was reviewed. She was rejected again.

“The system is designed for failure,” said Ms. Schoenfeld. “It’s designed to make it very, very difficult for people to vote.”

Did you miss our previous article...

https://trendinginthenews.com/usa-politics/fringe-scheme-to-reverse-2020-election-splits-wisconsin-gop