GUANTÁNAMO BAY, Cuba — Prosecutors and defense lawyers returned to the United States on Saturday from a first round of plea bargain talks that focused on how the five men who are accused of helping to plot the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, would serve out sentences in U.S. military custody.

No agreement was reached in the talks, which could resume in May after the court’s Ramadan recess. Negotiations could continue for months, some lawyers have predicted.

The case has been mired in pretrial proceedings for nearly a decade, much of them focused on the C.I.A.’s torture of the defendants. The talks are aimed at averting a death penalty trial by having Khalid Shaikh Mohammed and his four co-defendants plead guilty to conspiring in the hijackings that killed nearly 3,000 people in exchange for sentences of up to life in prison.

“All parties worked very hard during these three weeks to advance negotiations,” said Alka Pradhan, a lawyer for Ammar al-Baluchi, Mr. Mohammed’s nephew, who is accused of helping to transfer funds from the United Arab Emirates to some of the Sept. 11 hijackers.

She declined to offer specifics. But several parties to the talks said the sides were focusing on how the men would be held by the military as convicted war criminals.

Participants said the next step was for prosecutors to bring issues that require wider government involvement to the general counsel of the Defense Department, including whether the men could continue to be held in communal confinement and whether the Pentagon would offer civilian-run health care for victims of torture.

The Defense Department declined to comment on the negotiations. A spokesman, J. Todd Breasseale, said more broadly that the Biden administration was “committed to the responsible closure of the detention center at Guantánamo Bay.”

The Continuing Aftermath of the 9/11 Attacks

- 20th Anniversary: Two decades later, this single day continues to shape the U.S. and what it means to “never forget.”

- 9/11 Photographs: We asked Times photographers to reflect on the images they captured from the attacks and their aftermath.

- Effects on Survivors: Hundreds of thousands of people were exposed to toxic material in the attacks. Years later, they are still getting sick.

- One Conspiracy’s Effect: A conspiracy film energized the “9/11 truther” movement. It also supplied the template for the current age of disinformation.

“Resolution of the military commission process through trial or by negotiated settlement contributes to that goal,” he said.

The talks began in earnest on March 10 at the invitation of a lead prosecutor, Clayton G. Trivett Jr. He was authorized to hold them by the overseer of military commissions, Jeffrey D. Wood, who would be responsible for approving any deal.

The trial judge, Col. Matthew N. McCall, had traveled to Guantánamo Bay days earlier for three weeks of hearings but never held them. Instead, he ceded the courtroom to the negotiations, with prison guards shuttling the defendants to court most days.

Defense lawyers consulted the prisoners in the courtroom and in nearby holding cells, then would meet with prosecutors apart from the defendants, according to people with knowledge of the discussions. Just like during court hearings, all activities stopped for designated prayer times, with Mr. Mohammed and the other prisoners worshiping on prayer rugs they brought from prison to court.

On March 17, the judge canceled the entire hearing in an order that quoted prosecutors as saying “significant enough progress” had been made “in exploring possible plea agreements.”

This is not the first time lawyers have discussed a plea bargain in the Sept. 11 case. In 2017, a key demand in failed negotiations sought guarantees that the men would serve their sentences at Guantánamo and not be sent to the supermax prison in Florence, Colo., where federal convicts spend 23 hours a day in solitary confinement.

This time, one participant said, a focus was seeking assurances related to how the men would be held as military prisoners, rather than pressing for a particular venue. The men want guarantees that, even after their convictions, they would be able to eat and pray communally, as they have done in recent years, rather than in solitary confinement, which was how they were held in the C.I.A.’s secret black site prison network from 2002 to 2006, and earlier in their Guantánamo stay.

The detainees are also said to be seeking assurances that the military will commit to providing them with civilian-staffed health care, including psychological and physical rehabilitation from their torture in C.IA. custody.

Their care is currently provided by military medical staff members who serve short tours of duty and are forbidden to ask about what happened to them in C.I.A. custody, constraining the ability of caregivers to treat them.

Independent doctors and testing have found that the defendants suffer from brain injuries, rectal damage, memory loss, sleep and digestion disorders and sensitivity to light. The defendant Ramzi bin al-Shibh believes that his captors are remotely inflicting pinprick pain to parts of his body, according to his lawyers, and for years accused the United States of intentionally vibrating his bed in an orchestrated campaign of sleep deprivation.

Another unresolved issue is whether some of the men could serve their sentences in the custody of another country.

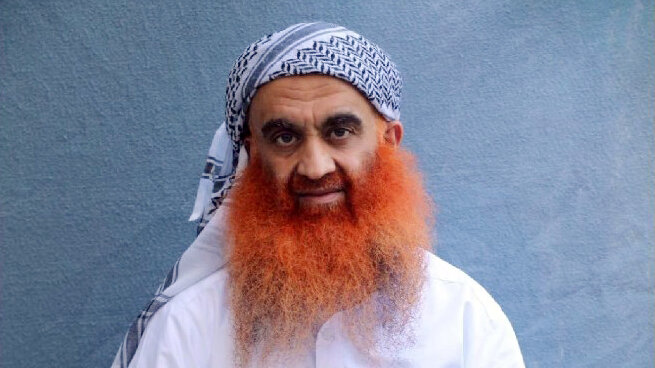

The defendant Mustafa al-Hawsawi, 53, a citizen of Saudi Arabia, could be a candidate for that. His lawyer has described him — a slight, malnourished-looking man — as the sickest of the five. He has painful damage to his rectum from a tear he experienced in C.I.A. custody, chronic high blood pressure, cervical disc disease, frequent migraines and ringing in his ears.

Such a transfer would not be unprecedented for a military commission convict. David Hicks, an Australian man who fought alongside the Taliban, served the remainder of his sentence in Australia under a deal arranged during the George W. Bush administration. Omar Khadr, a confessed “child soldier,” was sent to his native Canada to complete his sentence during the Obama administration. And the Trump administration repatriated a Saudi man, Ahmed Muhammed Haza al-Darbi, to serve the last nine years of a 13-year sentence.

Some participants said prosecutors and defense lawyers might continue discussions in the Washington area in April, which this year coincides with Islam’s holy month of Ramadan.

But none of the discussions are likely to involve the men at Guantánamo. Military judges in the Sept. 11 case have traditionally recessed for Ramadan, and the prisoners’ lawyers have typically voluntarily suspended meetings at the prison, where commanders shift operations to allow inmates to conduct more activities at night in consideration of the daylight fasting holiday.

The next hearing is scheduled to be held from May 9 to May 27.

But it may have to be postponed as well. The judge this week permitted Cheryl Bormann, who has served as the capital defense lawyer for the defendant Walid bin Attash for a decade, to quit the case. The chief defense counsel, Brig. Gen. Jackie L. Thompson Jr. of the Army, was scrambling to hire a replacement before the court goes back into session.