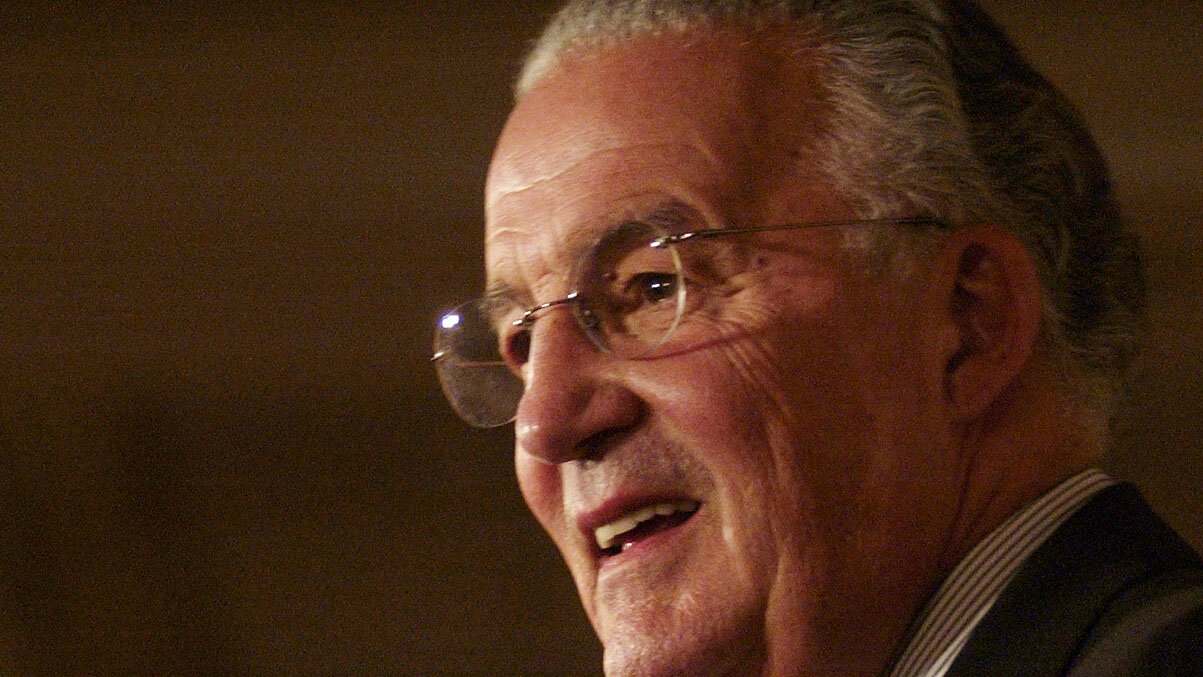

Former Maryland Senator Paul S. Sarbanes, a publicity-shy lawmaker who wrote legislation to curb fraudulent accounting practices that led to huge investor losses and major corporate bankruptcies in 2001 and 2002 and counseled Democratic Party leaders on a variety of issues, died on Sunday. He was 87.

Judy Keenan, a longtime aide, said she did not know the exact cause of death, but that he had heart problems. She said Mr. Sarbanes died while watching the Georgia Senate runoff debate.

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, adopted in response to the scandals involving Enron and other companies, strengthened corporate governance and created a new federal oversight board for the accounting industry. It curbed accounting firms’ consulting work for companies they audited and required them to judge internal fraud controls at those companies. It also required chief executives to certify audits personally, attesting to their accuracy.

But while other members of Congress pursued the Enron scandal with splashy televised hearings and spirited denunciations, Mr. Sarbanes approached it by holding 10 thorough, quiet, even dull hearings to get widespread expert advice on what corrective legislation should include.

Initially opposed by many Republicans and the powerful lobbying of the accounting industry, the measure eventually passed 97 to 0 in the Senate, when the stock market fell sharply after another accounting failure at WorldCom.

The House had originally passed a weaker measure, but agreed to a compromise that was basically the Senate bill. The law’s title included the name of Michael G. Oxley, chairman of the House Financial Services Committee.

Mr. Sarbanes headed the Senate Banking Committee for 18 months in 2001 and 2002. In 2001 he pushed through the committee a measure giving the government more ability to track money laundering involving terrorism, a bill that became part of the Patriot Act.

He also served on the Foreign Relations Committee, where he supported multilateral institutions like the United Nations and the World Bank. He voted against resolutions in 1991 and 2002 authorizing war against Iraq. The first senator of Greek-American heritage, he frequently supported Greece, saying that the United States was unduly friendly to its antagonist Turkey.

Having his name in headlines over the accounting measure was a rare moment in his 30 years in the Senate. He avoided publicity and scoffed at repeated attempt by Maryland Republicans to label him a “stealth senator.”

But, as he said in an interview for this obituary in 2013, “my career sort of has bookends,” closing with the accounting law but beginning in 1974 with his role in the impeachment proceedings against President Richard Nixon.

In the second of three terms in the House and a member of the Judiciary Committee, Mr. Sarbanes was given the assignment of introducing and defending, on national television, the critical first article of impeachment charging Mr. Nixon with obstruction of justice.

It was a surprise assignment. The chairman, Peter W. Rodino Jr., called Mr. Sarbanes to his office shortly before the committee met and gave him the task. Mr. Rodino had been impressed with the 41-year-old lawmaker’s “intellectual honesty” and legal mind, Francis O’Brien, a key committee aide at the time, said years later. The article was approved on a bipartisan 27 to 11 vote. The committee approved two other articles, but Mr. Nixon resigned before the full House could vote on them.

Mr. Sarbanes played a similar role on another highly emotional issue four years later. As a freshman senator in 1978, he was on the Senate floor almost constantly, explaining and defending the treaties turning the Panama Canal over to Panama.

Approving the pacts, he told the Senate, “will make these treaties a historic achievement for the American people, and for the protection of American interests. It will show a great power bringing might and right into harmony.”

But for most of this Senate career, Mr. Sarbanes operated quietly. He said in 2013, “I was doing a lot. I just didn’t make a lot of noise about it.” Or, as George J. Mitchell, Democratic majority leader from 1987 to 1994, observed: “Paul was effective because he didn’t seek credit, which endeared him to his colleagues.”

Mr. Mitchell, like his predecessor as leader, Robert C. Byrd, sought Mr. Sarbanes’ help and advice on difficult issues over a wide range of subjects, especially those relating to the economy. Mr. Sarbanes served two two-year terms as the chairman of Congress’ Joint Economic Committee.

Thomas A. Daschle, the Democratic leader from 1995 to 2006, said in 2013 that when he was “trying to persuade the caucus to do something difficult, I would use Paul to bring it home, to close the argument.”

In the tense days of President Bill Clinton’s impeachment trial in 1999, Mr. Daschle said: “My whole goal was to keep the caucus as unified as possible, and I would ask Paul to summarize in a compelling way what the issue was. He had such a great legal mind.”

While Mr. Sarbanes compiled a 95 percent liberal voting record, according to Americans for Democratic Action, a progressive group, some of his liberal allies grumbled that he often stayed away from partisan fights when they saw Republican vulnerabilities.

Paul Spyros Sarbanes was born in February 1933, in Salisbury, on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. He was the son of two Greek immigrants, Spyros P. Sarbanes and Matina Tsigounis Sarbanes, who ran the Mayflower restaurant in Salisbury. The family lived upstairs.

A star student and athlete at Wicomico High School, Mr. Sarbanes had local college ambitions until a Princeton alumnus visited the school and met him. A full scholarship made him the first student from Wicomico to go to Princeton.

Mr. Sarbanes graduated in 1954 and won a Rhodes Scholarship, attending Balliol College at Oxford and taking a second bachelor’s degree in 1957. He earned a law degree at Harvard in 1960.

He clerked for a federal judge, worked as an aide to Chairman Walter W. Heller of President Kennedy’s Council of Economic Advisers, practiced law in Baltimore and was executive director of a commission writing a new City Charter for Baltimore.

In 1966 he ran for a seat in Maryland’s House of Delegates and won, and in 1970 he challenged a 13-term House veteran, George H. Fallon, who was chairman of the pork-barrel-rich House Committee on Public Works. Campaigning door to door with his wife, the former Christine Dunbar, whom he met at Oxford, Mr. Sarbanes stressed the issues of Vietnam and the environment. He won with 52 percent of the vote to the incumbent’s 45 percent.

Redistricting after the 1970 census pushed Mr. Sarbanes into another potential race against a House committee chairman, Edward A. Garmatz, who headed the Committee on Merchant Marine and Fisheries, which was very important to the port of Baltimore. But Mr. Garmatz retired, and Mr. Sarbanes won re-election easily.

He was then elected to the Senate in 1976, defeating Senator J. Glenn Beall Jr., a Republican. He was attacked in 1982 by the National Conservative Political Action Committee, which had used the Panama Canal issue in 1980 to help defeat several Democratic senators. But Mr. Sarbanes won comfortably then and again in 1986, 1992 and 1998 before announcing in 2005 that he would not run again in 2006.

He is survived by a brother, Anthony Sarbanes; a sister, Zoe Pappas; two sons, Representative John P. Sarbanes, who holds his father’s old seat in the House, and Michael Sarbanes; a daughter, Janet Sarbanes; and several grandchildren. His wife, Christine, died in 2009 after 48 years of marriage.

Mr. Sarbanes was always attentive to local issues, leading the effort to clean up the Chesapeake Bay after another Maryland senator, Charles McC. Mathias, retired in 1984. He also pushed for federal support of mass transit, and a transit center in Silver Spring, Md., is named for him.

Unlike many senators, after retiring he rejected the idea of taking a position at a Washington law firm. If he had, he told friends, sooner or later he would be asked to take on the distasteful chose of lobbying a former colleague.

Adam Clymer, a reporter and editor at The Times from 1977 to 2003, died in 2018. Jenny Gross contributed reporting.