As vice president, Joseph R. Biden Jr. led the Obama administration’s “cancer moonshot,” a major public investment in the search for a cure.

On Thursday, President Biden announced another Hail Mary — what Jennifer Granholm, the energy secretary, called “our generation’s moonshot.” This time, the focus is on finding a cure for the entire planet.

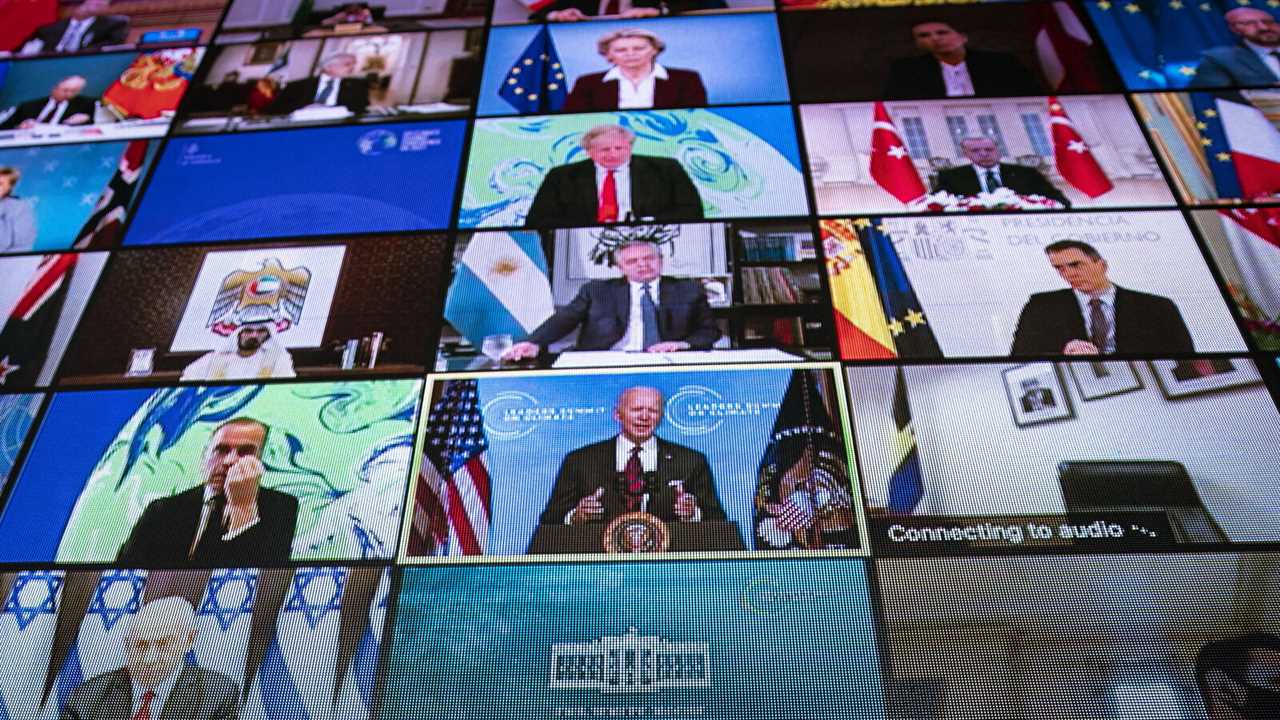

In a speech yesterday kicking off the White House’s virtual climate summit with world leaders, Mr. Biden set a goal of cutting the United States’ carbon emissions to half their 2005 levels by 2030 — the most ambitious target in history from a U.S. president combating the effects of climate change.

Mr. Biden said the effort would touch all sectors of the nation’s economy. And he acknowledged that it would mean working closely with the international community, which was thrown for a loop after President Donald J. Trump reneged on the United States’ commitment to the Paris climate accord.

“Scientists tell us that this is the decisive decade,” Mr. Biden said. “This is the decade we must make decisions that will avoid the worst consequences of a climate crisis.”

While environmental activists mostly welcomed the news, saying the commitment comes at least somewhere close to matching the scale of the problem, experts have cautioned that Mr. Biden’s target is just what Ms. Granholm says it is: a moonshot. That was underscored by a report released just days ago by the International Energy Agency, which found that demand for coal is still on the rise around the world.

To get a handle on how Mr. Biden’s international commitments will need to jibe with his domestic policy agenda, I called Nathaniel Keohane, the economist and former Obama adviser who now serves as senior vice president for climate at the Environmental Defense Fund. The interview has been lightly edited and condensed.

Hi Nathaniel. From the environmental community’s perspective, how expected or unexpected was Biden’s pledge to cut U.S. greenhouse gas emissions to half of their 2005 levels by 2030?

Well, this matched the level of ambition that we’ve been calling for, and that the business community has been calling for: at least 50 percent. We’re seeing an administration that is willing to go bold when the moment demands it. We’ve seen this across the board in other areas of policy, and we’re seeing it in climate change now. The president clearly meant it when he said that the climate crisis is one of the four crises he is going to be focused on in his presidency. There’s obviously huge amounts of work to be done to implement that target, but in terms of the level of ambition, that’s what we needed. It’s in line with the president’s target of net zero emissions by 2050, which is what the science demands.

And it’s also at least in the top tier of ambition globally — not quite as ambitious, of course, as the E.U.; not nearly as ambitious as the U.K. But it compares favorably with the rest of the world, and it puts the U.S. in the top tier, which is where it should be as the largest historical emitter over time and as the second-largest emitter today.

How much trouble is Biden going to have in taking a leadership role with the international community after Trump withdrew the United States from the Paris climate accord?

It is a real issue. There’s a credibility deficit that the United States faces. I think President Biden and his team understand that, and they’re conscious of doing what they can to address it. This kind of ambitious target is a good first step. But I think some of that skepticism and wariness will persist until this administration can put in place some real concrete policies that will help achieve that 50 percent reduction.

Live Updates: Global Climate Summit

- California’s governor seeks to ban new fracking and halt oil production, but not immediately.

- An Arizona judge temporarily halts a G.O.P. effort to recount 2020 ballots.

- Biden meets virtually with the Pentagon’s senior military and civilian leaders.

You heard Xi Jinping, the president of China, in his speech yesterday making a thinly veiled allusion to this, talking about the importance of countries continuing in a straight path and being consistent rather than going back and forth. I think everybody knew he was talking about the U.S. Certainly, as I’ve heard in conversations with folks in Europe, there is concern about what will make this durable and credible.

Yesterday, the climate activist Bill McKibben wrote in a New Yorker article about Biden’s commitment: “It’s big enough, and a hard enough target, that meeting it would likely occupy the attention of his entire presidency.” That suggests that all of Biden’s major proposals would need to take climate sustainability seriously into account. Looking at his next big priority — a landmark infrastructure package — to what degree could that legislation help to set the United States on a new course?

The infrastructure bill is crucial. It’s going to be the first big test of whether he does what Bill talked about — which is making climate central to the focus of his presidency. The other way of saying it is that you need a whole-of-government approach.

It is vital that the infrastructure bill include a massive investment in low-carbon and clean-energy technologies and infrastructure; supporting the deployment of electric vehicles and electric-vehicle infrastructure; supporting a cleaner grid, more transmission; supporting supply chains to make sure that electric vehicles and batteries are produced here at home. It is really going to be necessary for the administration to lean in.

If the bill is split into two parts, then the administration is going to need to be willing to make sure that one of those is something that reflects the urgency of the moment, in terms of investment in low-carbon and clean-energy infrastructure — as well as in climate resilience, because this is an issue that affects the entire economy.

The other reason the infrastructure bill is so important is that for the Biden administration to succeed in this effort — for it to become durable politically, so it doesn’t flip-flop back and forth in the way we were just talking about — the administration needs to show that investments in clean energy are also investments that create jobs, that drive the economy, that lead to cleaner air and healthier communities, especially in frontline disadvantaged communities that have borne the brunt of pollution historically. The Biden administration needs to show that a low-carbon agenda is also one that brings better outcomes for people in their everyday lives. And that’s what infrastructure spending, in some ways, can do most of all.

I think if they do that, and you see the economy rebounding in the coming years and you see that in the context of real investment in clean energy and low-carbon transition, that will help build the political will and the popular support to keep pushing on climate and clean energy over the coming decade.

Put more simply, you don’t get the 50 percent cut by 2030 without putting climate and clean energy at the center of this infrastructure bill this year.

What about the fact that some states have been doing a much stronger job than the federal government at leading the way on clean-energy policy? To what degree have states been modeling policies that the federal government can adopt, and how much does Biden’s team still need to innovate its own solutions?

The states are going to play a critical role — they played a critical role. Not just states, but cities and companies. The last four years, when Washington, D.C., was out of the picture, cities and states and companies carried the load. And states in particular, as you say, have really led the way on innovative policies to drive down emissions and carry their economies forward: California and New York, but also Colorado — which has the toughest economy-wide statutory target on emissions in the country. You’ve got Hawaii pioneering the way in renewable energy. This is happening across New England, it’s happening in the Midwest.

But the states can’t do it alone. They can be models for policy: What California has done on tailpipe emissions and electric vehicles can be a model for the rest of the country. That can be a model for doing it at a federal level. So the policy models are there, and states can lead the way in that sense. But it’s going to require federal action if we’re going to get to that 50 percent cut by 2030. This needs to be an all-of-government approach that employs all the levers we have.