PHOENIX — Jade Duran once spent her weekends knocking on doors to campaign for Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, the stubbornly centrist Democrat whose vote could seal the fate of a vast Democratic effort to remake America’s social safety net. But no more.

When Ms. Sinema famously gave a thumbs down to a $15 minimum wage and refused to eliminate the filibuster to pass new voting-rights laws this year, Ms. Duran, a Democrat and biomedical engineer from Phoenix, decided she was fed up. She joined dozens of liberal voters and civil-rights activists in a rolling series of protests outside Ms. Sinema’s Phoenix offices, which have been ongoing since the summer. Nearly 50 people have been arrested.

“It really feels like she does not care about her voters,” said Ms. Duran, 33, who was arrested in July at a protest. “I will never vote for her again.”

Ms. Sinema, a onetime school social worker and Green Party-aligned activist, vaulted through the ranks of Arizona politics by running as a zealous bipartisan willing to break with her fellow Democrats. She counts the late Republican senator John McCain as a hero, and has found support from independent voters and moderate suburban women in a state where Maverick is practically its own party.

But now, Ms. Sinema is facing a growing political revolt at home from the voters who once counted themselves among her most devoted supporters. Many of the state’s most fervent Democrats now see her as an obstructionist whose refusal to sign onto a major social policy and climate change bill has helped imperil the party’s agenda.

As one of two marquee Democratic moderates in an evenly divided Senate, little can proceed without Ms. Sinema’s approval. While she has balked at the $3.5 trillion price tag and some of the tax-raising provisions of the bill, which is opposed by all Republicans in Congress, Democrats in Washington and back home in Arizona have grown exasperated.

While the Senate Democrat’s other high-profile holdout, Joe Manchin III of West Virginia, has publicly outlined his concerns with key elements of the Democratic agenda in statements to swarms of reporters, Ms. Sinema has been far more enigmatic and has largely declined to issue public comments.

Mr. Biden, White House officials and Democrats have beseeched the two senators to publicly issue a price tag and key provisions of the legislation that they could accept. But there is little indication so far that Ms. Sinema has been willing to offer that, even privately to the administration.

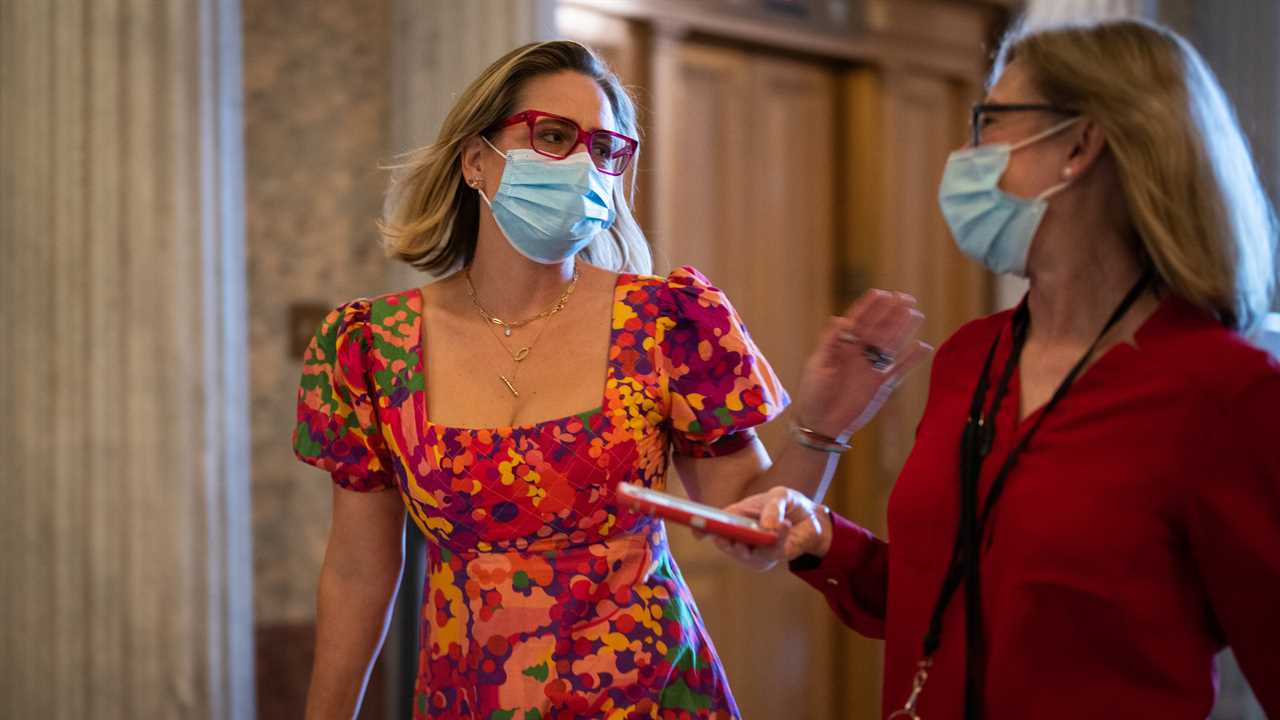

On Wednesday afternoon, she and a team from the White House huddled in her office for more than two hours on another day of what a spokesman for Ms. Sinema called good-faith negotiations.

“Kyrsten has always promised Arizonans she would be an independent voice for the state — not for either political party,” John LaBombard, a spokesman for the senator, wrote in an email responding to questions for the senator about her standing at home. “She’s delivered on that promise and has always been honest about where she stands.”

That posture helped her win election to the Senate in 2018 from a state whose voters are roughly 35 percent Republican, 32 percent Democratic and 33 percent “other.” And for all the passions of the moment, Ms. Sinema is not up for election again until 2024.

A breakthrough on the legislation could quell much of the criticism and burnish Ms. Sinema’s image as a deal-maker who shepherded a related bipartisan infrastructure bill through the Senate. But liberals on Capitol Hill do not trust that she is actually willing to support the broader spending package.

“This discussion has been going on for months — for months,” said Senator Bernie Sanders, the Vermont independent in charge of the Senate Budget Committee, in an interview. He added, “we need some definitive results.”

Democrats familiar with the ongoing discussions with Ms. Sinema and her staff say that she has deep concerns with the current proposals around certain tax increases, which could shape the scope of the package.

In the closely divided Phoenix suburbs that were crucial to Democrats’ recent wins in Arizona, some exhausted voters said they were deliberately tuning out the fractious negotiations in Washington and the threats of a government shutdown.

But others said they had been calling and writing Ms. Sinema for months and now worried that the Democrats’ best chance to advance major policies was slipping away because of their senator.

Over the weekend, the state’s Democratic Party threatened a symbolic vote of no confidence against Ms. Sinema. Dissatisfied Democratic donors and activists are launching a Primary Sinema political action committee to raise money to fund primary challengers in 2024 if she blocks the Democratic agenda in Washington.

At the same time, House Democrats are now threatening to derail the trillion-dollar bipartisan infrastructure bill hammered out by Ms. Sinema that has already passed the Senate.

The turmoil is not just testing Ms. Sinema’s strategy of staying in the middle lane, but also Arizona’s changing political trajectory.

Democratic activists believe Ms. Sinema’s political future — and Arizona’s — lies in the growing number of left-leaning Latino and young voters in Phoenix and the fast-growing cities of surrounding Maricopa County, home to about 60 percent of Arizona’s 7.3 million residents. They point to some surveys showing support for Democratic proposals to expand Medicare, provide more child care or expand tax cuts to working-class people.

But while President Biden did become the first Democrat in 25 years to win Arizona, his margin was a thin 10,500 votes, and Arizona’s governor and state Legislature are still controlled by Republicans.

“She is a Democratic senator elected in a center-right state,” said Kirk Adams, a former Republican speaker of the Arizona House. “She is purposefully tapping into that independent streak that a large section of Arizona voters have always had.”

Ms. Sinema’s standing with Democrats has suffered as she takes fire for defending the Senate filibuster as a guardrail of democracy. About 56 percent of Democrats in the state viewed Ms. Sinema favorably, compared with 80 percent for her fellow Democrat Sen. Mark Kelly, according to a September poll from OH Predictive Insights, a Phoenix political research firm.

In the sprawling valley east of Phoenix, Augie Gastélum, an independent voter who once considered Ms. Sinema too liberal, said he believed in her positions on bipartisan cooperation. He worried that scrapping the filibuster would provoke an arms race of increasingly extreme laws and further tear apart a divided country.

But Mr. Gastélum, 40, who is from Mexico, became a citizen last year after decades of living undocumented. His support for incremental change is now being strained because he longs to see immigration reform.

“There’s part of me that says, blow it up and get it taken care of,” he said. “But the long-term consequences could be so devastating.”

While left-wing Democrats may be frustrated with Mr. Manchin, he has not faced nearly the same level of backlash at home in his Trump-supporting state of West Virginia, where he served as governor and has been a political fixture for decades.

But in Phoenix, Ms. Sinema’s office building overlooking the crags of Piestewa Peak in the affluent Biltmore neighborhood has become a new magnet for her frustrated supporters.

On some days, people crowd the building pushing Ms. Sinema to support voter-rights laws and immigration reform. Other days, student-led groups arrive with banners telling her to do more to curb fossil fuel emissions and climate change.

They criticized her for holding a fund-raiser with business lobbying groups that oppose tax hikes in the Democrats’ main spending bill.

Many of the youngest activists now agitating the loudest against Ms. Sinema said they felt betrayed because she seemed so much like them. At 45, she is practically a teenager by the Senate’s octogenarian standards. She is an Ironman triathlete, the first openly bisexual member of Congress and, as someone who claims no religion, was sworn in on the Constitution rather than a Bible.

“I believed in what it would mean to have a queer representative who believed in the climate crisis,” said Casey Clowes, 29, who has demonstrated outside Ms. Sinema’s offices with the Sunrise Movement, a youth-led group focused on climate change. “I knocked on doors for her. I was an intern for her campaign. I really believed.”

Mary Kay Yearin, a lifelong Democrat who lives in Scottsdale, said she and her wife were both frustrated that Ms. Sinema had not embraced proposals to address abortion rights, voter rights and, above all, climate change.

Ms. Yearin worried that a fast-warming climate could soon dry up the Lake Powell and Lake Mead reservoirs that water the West, which would make the state nearly uninhabitable in the summers to come. She said the environmental catastrophes facing the country were too dire for a cautious, incremental approach.

“Her vote matters so much,” Ms. Yearin said. “She seems like a Republican in Democrat’s clothing.”

While most conservatives broadly disapprove of both of Arizona’s Democratic senators, Ms. Sinema’s stubborn centrism has bought her some Republican support. Older voters, rural Arizonans and voters who watch Fox News approved of Ms. Sinema in a recent public poll while also saying they did not favor her Democratic colleague, Senator Kelly.

Ms. Sinema’s defense of the filibuster brought grumbles of approval one recent afternoon from the conservative members of the Rusty Nuts classic car club who were gathered around a table at the American Legion hall in Chandler, a Phoenix suburb where many voters split their ballots in 2018 to vote for Ms. Sinema for Senate and Doug Ducey, a conservative Republican, for governor.

“I appreciate that she’s not way left-leaning like the rest of them,” said Pat Odell, a retired court clerk and conservative. Ms. Odell said she wanted to see a total closure of the Southern border and wanted Ms. Sinema to reject the $3.5 trillion Democratic social-spending bill outright.

But even if that happened, would Ms. Odell actually vote for Ms. Sinema or anyone with a D beside their name?

Probably not, she said.