For years, Democrats have preached the gospel of changing demographics.

As the country grew more diverse, they argued, the electorate would inevitably tilt in their favor and give their party an unbeatable edge.

Well, the country is more racially diverse than ever before. But exit polls suggest that Joe Biden lost ground among Latino, Black and Asian-American voters in 2020 compared with Hillary Clinton’s performance in 2016.

Demographics, it turns out, are not political destiny. But diplomas just might be.

The clearest way to understand the results of the 2020 election — and, perhaps, the shifting state of our politics — is through the education voting gap. Voters with college degrees flocked to Mr. Biden, emerging as the crucial voting bloc in the suburbs. Those without them continued their flight from the Democratic Party.

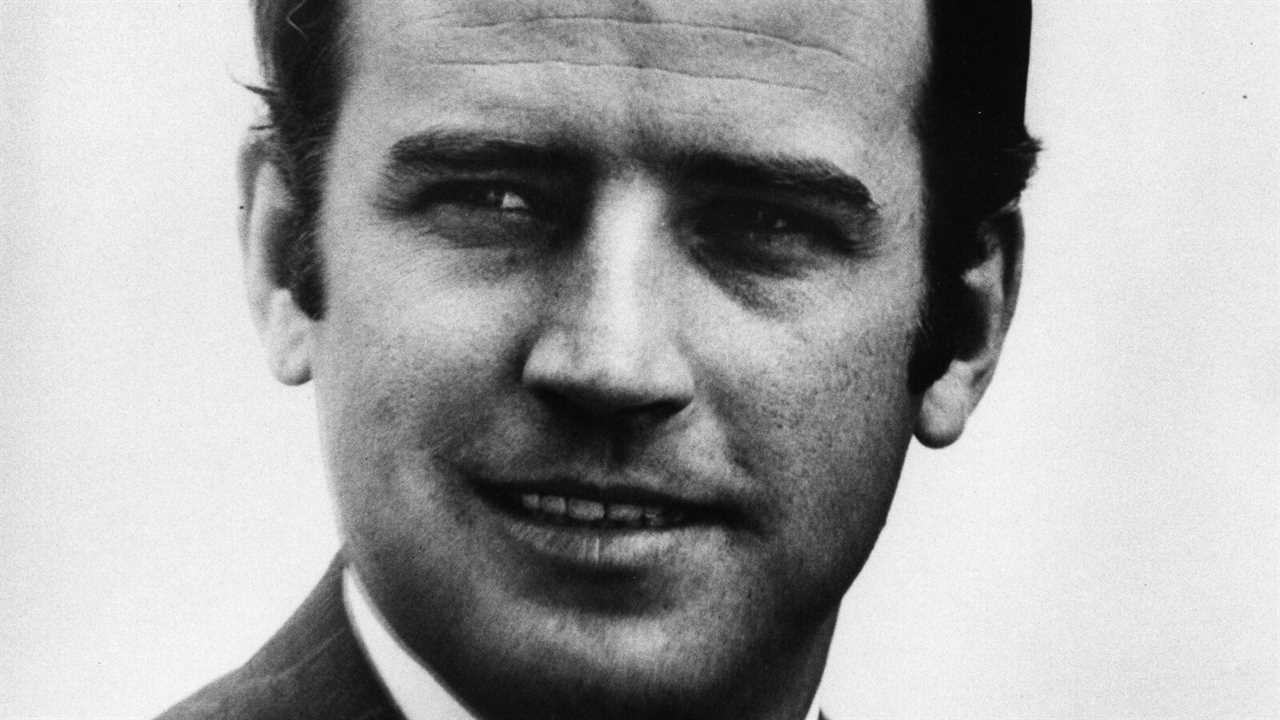

“The big-picture problem is that the Democratic Party is increasingly reflecting the cultural values and political preferences of educated white people,” said David Shor, a data scientist who advises Democratic campaigns and organizations. “Culturally, working-class nonwhite people have more in common with working-class white people.”

The shifts were at the margins: Voters of color still overwhelmingly backed Mr. Biden, sticking with the Democratic candidate as they had for decades. But these small swings hint at the possibility of a broader realignment in American politics. Political parties, after all, are dynamic. Coalitions can and do change.

Think about how Democrats have won over the past four years. In 2018, they flipped affluent, diversifying inner-ring suburbs and ran up their margins in cities to gain control of the House of Representatives. Mr. Biden followed that same path to the presidency: A New York Times analysis found that he improved on Mrs. Clinton’s performance in suburban counties by an average of about five percentage points.

What else do these areas have in common? They are more likely to be dominated by highly educated voters.

One way to examine this trend county by county is to look at the number of voters who have white- or blue-collar jobs. (I know, your buddy never graduated from college and now makes a killing as a real estate broker. It’s not a perfect metric but a pretty good proxy for education, given the economic data available.)

The results were striking. Of the 265 counties most dominated by blue-collar workers — areas where at least 40 percent of employed adults have jobs in construction, the service industry or other nonprofessional fields — Mr. Biden won just 15, according to data from researchers at the Economic Innovation Group, a bipartisan policy research group.

On average, the work force in counties won by Mr. Biden was about 23 percent blue collar. In counties won by President Trump, blue-collar workers made up an average of 31 percent of the work force.

This isn’t a new trend. For decades, Democrats have been trading the support of union members for broader backing from the professional classes. And the G.O.P., once the party of white college-educated voters, has increasingly found support among white working-class voters.

Many Democratic primary voters saw Mr. Biden as uniquely positioned to cut into the Republican advantage with the working class. For decades, he’s built his political brand on being a scrappy kid from Scranton, Pa., who became just another guy riding the train to work. The rallying cry of his campaign in the final weeks was: “This election is Scranton versus Park Avenue.”

But Mr. Biden fared worse than Mrs. Clinton in 2016 and Barack Obama in 2012 and 2008 in counties dominated by blue-collar workers.

That outcome should scare Democratic strategists about their party’s future, Mr. Shor said, because of structural dynamics like the Electoral College that give rural areas political influence far beyond the size of their population.

If Democrats can’t win blue-collar workers in less-populated areas — or at least cut some of their losses — winning control of the Senate or the White House will become very difficult. And with Republicans maintaining their hold on state legislatures, Democrats may find themselves cut out of some of those friendlier suburban House seats when districts are redrawn after the census.

“It’s very hard for us to imagine us taking the Senate between now and the end of the decade,” Mr. Shor said. “And it would be very hard just to win the presidency. Our institutions are very biased specifically against this coalition we are putting together.”

What is happening with Georgia Republicans?

Georgia is on my mind this week. (Yes, I know, low-hanging cliché.)

With control of the Senate hinging on the two runoff elections there, the political world is pouring money and resources into the state. But as we reported this week, things are getting a little … complicated.

Unsurprisingly, the cause of the political chaos is President Trump. As he continues to push baseless allegations about the presidential election results in Georgia — a state he lost — Republicans are getting nervous that his attacks could depress their turnout in the Jan. 5 runoffs.

Some Trump allies in the state have urged conservatives to boycott the election or write in Mr. Trump’s name — an option that’s not even provided on the runoff ballot. Though Mr. Trump and his campaign have tried to distance themselves from that effort, they’ve continued their drumbeat of attacks on Gov. Brian Kemp, a Republican, and other G.O.P. election officials. Some Republican strategists were worried that rhetoric could further alienate suburban voters, who helped deal Mr. Trump his loss in Georgia but might be more receptive to the Republican runoff candidates, the incumbent Senators Kelly Loeffler and David Perdue.

Mr. Trump is scheduled to campaign with them in Valdosta, Ga., on Saturday. Republicans are uncertain whether his remarks could do more harm than help, particularly if he remains unable to put aside some of his personal pique about his own loss.

The situation offers a preview of the kind of political dynamics that Republicans could face even after Mr. Trump leaves office as they try to navigate his continuing ambitions. With the president considering another run for the White House in 2024, his political aspirations may not align with Republicans’ goals in a divided Washington.

By the numbers: $908 billion

… That’s the new starting point in negotiations for another pandemic relief bill.

With coronavirus cases spiking and the economy showing signs of weakening, Democrats made a big concession — they had been demanding at least $2 trillion — to prod Republicans and the Trump administration into compromise legislation.

Along with ending a monthslong congressional stalemate, passage of stimulus legislation could help the new Biden administration enter office on slightly stronger economic footing.

… Seriously

I did not think anything could outdo Rudy Giuliani’s dripping face.

I was wrong.