The American jobs machine tottered last month, confounding optimistic forecasts of the labor market’s recovery and sharpening debates over the impact of federal pandemic-related jobless benefits on the nation’s work force.

Employers added 266,000 jobs in April, the government reported Friday, far below the gains registered in March. The jobless rate rose slightly, to 6.1 percent, as the labor force grew faster than the number of jobs.

“It turns out it’s easier to put an economy into a coma than wake it up,” Diane Swonk, chief economist for the accounting firm Grant Thornton, said of the disappointing report. Economists had forecast an addition of about a million jobs.

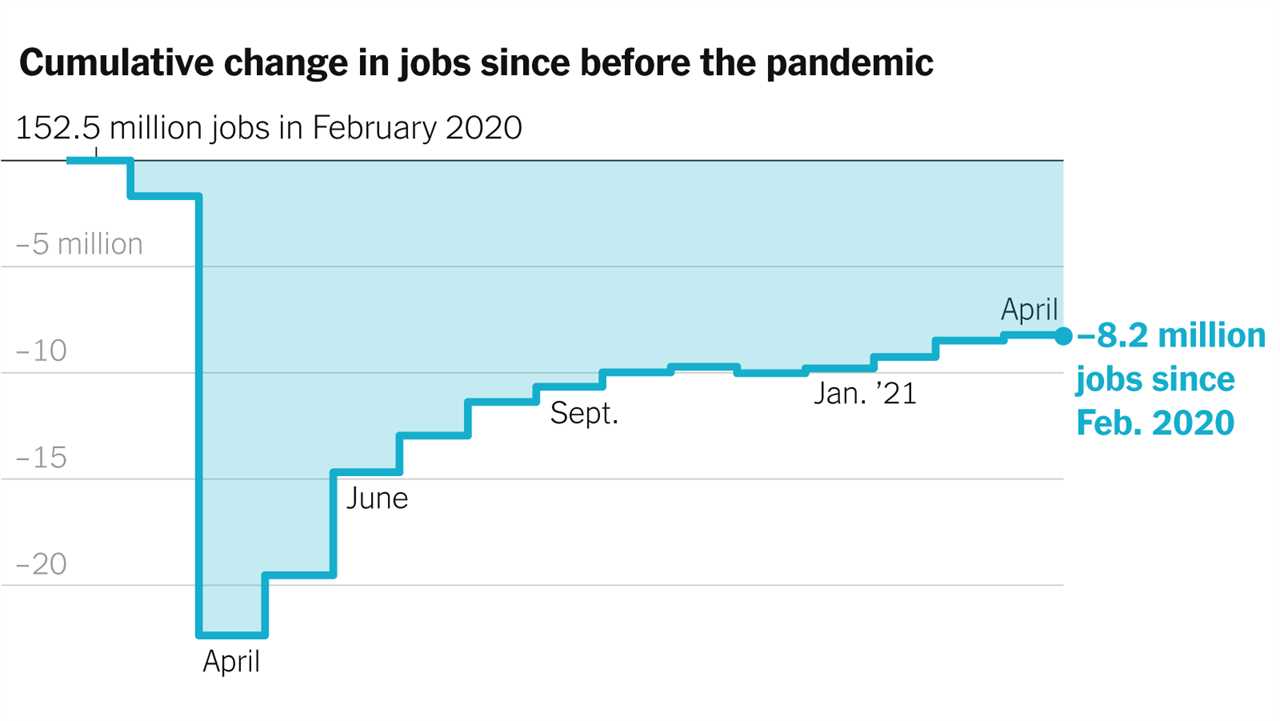

The prolonged uncertainty generated by a virus that killed millions around the world has not yet dissipated, creating skittishness among employers and workers. And there are still 8.2 million fewer jobs than existed before the pandemic.

Despite the modest rate of hiring in April, there are strong signals that the economy is returning to health as infections ebb, vaccinations continue, restrictions lift and businesses reopen. Economists still predict a big expansion in the course of the year.

The largest job gains in April were in leisure and hospitality, two industries that had been particularly hard-hit during the pandemic. But as the number of restaurant workers rose, the number of grocery store clerks and couriers declined.

The manufacturing sector lost 18,000 jobs even though consumer demand for goods has been strong. The Alliance for American Manufacturing blamed supply chain problems, noting that “drops in automotive sector employment are almost entirely due to semiconductor shortages.”

Economists, too, have raised concerns that supply bottlenecks in major industries could hamstring growth at a time when people are eager to buy.

As the economy fitfully recovers, there are divergent accounts of what’s going on in the labor market. Employers, particularly in the restaurant and hotel industries, have reported scant response to help-wanted ads. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce and Republican officials have faulted what they call overly generous government jobless benefits.

This week, the Republican governors of Montana, South Carolina and Arkansas said they planned to cut off federally funded pandemic unemployment assistance at the end of June.

That means jobless workers there will no longer get a $300-a-week federal supplement to state benefits, and the states will abandon a pandemic program that helps freelancers and others who don’t qualify for state unemployment insurance. (Montana will, however, offer a $1,200 bonus for unemployed workers who take jobs.)

“What was intended to be short-term financial assistance for the vulnerable and displaced during the height of the pandemic has turned into a dangerous federal entitlement, incentivizing and paying workers to stay at home,” declared Gov. Henry McMaster of South Carolina.

But federal regulations prohibit people from continuing to collect unemployment insurance if they turn down suitable work. And economists have found little evidence to indicate that unemployment benefits are discouraging people from working. At the same time, there are other potent forces constraining the return to work.

Less than half of adults are fully vaccinated, leaving most of the population at continuing risk of infection. Millions of Americans have said health concerns and child care responsibilities — with many schools and day care centers not back to normal operations — have kept them from taking a job.

Millions of others are considered temporarily laid off and say they are not actively job hunting because they expect to be hired back once businesses reopen fully.

A broader measure of unemployment is estimated to be about 8.9 percent, accounting for those who have stopped looking for work since the onset of the pandemic or who may be misclassified in the Labor Department data. The methodology used to arrive at that figure closely mirrors one Federal Reserve officials often cite.

“I do think it is a temporary issue,” Ben Herzon, executive director of U.S. economics at the financial services company IHS Markit, said of the impediments to hiring. By the fall, the risk of infection should drop further as vaccination rates climb. More schools will return to full-time instruction, and extended jobless benefits will expire. “I don’t think there’s anything that will prevent labor force participation and job growth,” Mr. Herzon said.

Workers say the real problems are poorly paid jobs with shifting schedules, few benefits and insufficient safety protocols. “The shortage of restaurant workers we are seeing across the country is not a labor-shortage problem; it’s a wage-shortage problem,” said Saru Jayaraman, president of One Fair Wage, a minimum-wage advocacy group.

Former food service workers and others may also be migrating to warehousing jobs with wages as high as $23 an hour and to customer service jobs that are done from home, said Amy Glaser, senior vice president at the staffing firm Adecco.

The most solid evidence of a real shortage of workers, economists say, would be a sustained rise in wages. The Labor Department report showed that hourly wages grew by 0.7 percent last month while the average number of hours worked per week increased slightly. But economists were cautious about interpreting the wage figure, which reflects a hodgepodge of factors. Wages could also be up because more higher-earning workers are joining the work force.

The broader debate about the availability of jobs as well as the costs and benefits of returning to work is playing out in cities all over the country.

Home Chef, a meal-kit delivery service owned by the supermarket giant Kroger that has seen business explode during the pandemic, has been hiring rapidly. The company employs about 2,000 hourly and salaried workers and expects to hire an additional 2,000 by the end of the year, said Patrick Vihtelic, the founder and chief executive.

“In recent weeks, we’ve seen a sharp decline in terms of the number of new job applicants at our plants, despite permanently increasing wages across each of our production facilities in recent months,” Mr. Vihtelic said of hiring at his three plants in San Bernardino, Calif.; Lithonia, Ga.; and Bedford Park, Ill.

He said the company had instituted more employee appreciation programs like paying for celebratory lunches, bringing in food trucks and offering morning coffee and doughnuts.

Despite the falloff in applicants, he is confident the company will get the workers it needs. “Our funnel hasn’t been filling as fast but there’s been no major service disruptions,” he said.

Gail Myer, whose family owns six hotels in Branson, Mo., has been having more trouble. “I talk to people all over the country on a regular basis in the hospitality industry, and the No. 1 topic of discussion is shortage of labor,” he said.

Before the pandemic, Mr. Myer said, there were about 150 full-time employees at his six hotels, but now staffing is down about 15 percent. Jobs at Myer Hospitality for housekeepers, breakfast attendants and receptionists are advertised as paying $12.75 to $14 an hour, plus benefits and a $500 signing bonus.

Returning to work is not yet an option for Lauren Fine, an education consultant in Denver. Ms. Fine, who is single and has a toddler, lost her job early in the pandemic. She initially collected unemployment benefits, but for the last nine months she has cobbled together jobs like tutoring and contract work.

She said she has been making less than half of her previous salary, creating something of an inescapable cycle: She cannot afford to send her son to day care for more than two days a week, and her child-care responsibilities are preventing her from taking a full-time job. In addition, she said, she has an autoimmune illness, making the possibility of contracting Covid-19 in the workplace especially harrowing.

“I like to say it’s just like spinning plates,” she said. Ms. Fine is considering giving up looking for a full-time job for the next year, until her son is old enough to attend school five days a week.

Jillian Melton worked for six years at a restaurant in Memphis before the pandemic, but she said the danger of infection coupled with low pay and babysitter costs make working not worth the risk right now. She is at home caring for her five children, including one with asthma, and her 93-year-old grandmother.

“I’ve attempted to go back to work twice, and it just doesn’t make sense,” she said. She interviewed for a job at a cigar bar, but said: “People weren’t wearing masks and weren’t staying separated and there was no hand sanitizer.”

Economists say it is natural for the transition from closure to reopening to be bumpy for a mammoth economy. Employers are wary, wanting to maintain flexibility over hours, pay and long-term commitments. Workers have demands at home and health concerns. Supplies have been redirected or have run out.

“It’s understandable — it’s going to take some time,” said Diane Lim, an economist who has worked at the White House and in Congress and now writes the blog EconomistMom.com. “You’re not just going to snap your fingers and get everyone back to work.”

Jeanna Smialek and Sydney Ember contributed reporting.

Did you miss our previous article...

https://trendinginthenews.com/usa-politics/marooned-at-maralago-trump-still-has-iron-grip-on-republicans