Sixteen months before last November’s presidential election, a researcher at Facebook described an alarming development. She was getting content about the conspiracy theory QAnon within a week of opening an experimental account, she wrote in an internal report.

On Nov. 5, two days after the election, another Facebook employee posted a message alerting colleagues that comments with “combustible election misinformation” were visible below many posts.

Four days after that, a company data scientist wrote in a note to his co-workers that 10 percent of all U.S. views of political material — a startlingly high figure — were of posts that alleged the vote was fraudulent.

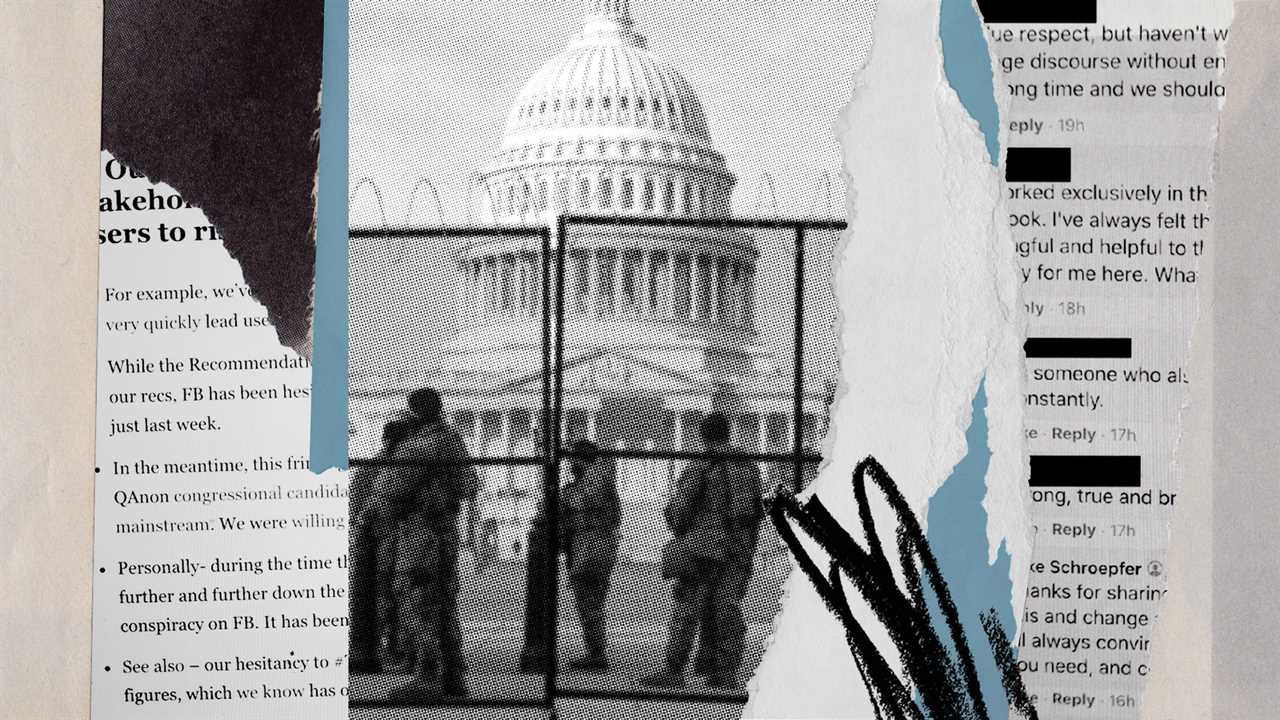

In each case, Facebook’s employees sounded an alarm about misinformation and inflammatory content on the platform and urged action — but the company failed or struggled to address the issues. The internal dispatches were among a set of Facebook documents obtained by The New York Times that give new insight into what happened inside the social network before and after the November election, when the company was caught flat-footed as users weaponized its platform to spread lies about the vote.

Facebook has publicly blamed the proliferation of election falsehoods on former President Donald J. Trump and other social platforms. In mid-January, Sheryl Sandberg, Facebook’s chief operating officer, said the Jan. 6 riot at the Capitol was “largely organized on platforms that don’t have our abilities to stop hate.” Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s chief executive, told lawmakers in March that the company “did our part to secure the integrity of our election.”

But the company documents show the degree to which Facebook knew of extremist movements and groups on its site that were trying to polarize American voters before the election. The documents also give new detail on how aware company researchers were after the election of the flow of misinformation that posited votes had been manipulated against Mr. Trump.

What the documents do not offer is a complete picture of decision making inside Facebook. Some internal studies suggested that the company struggled to exert control over the scale of its network and how quickly information spread, while other reports hinted that Facebook was concerned about losing engagement or damaging its reputation.

Yet what was unmistakable was that Facebook’s own employees believed the social network could have done more, according to the documents.

“Enforcement was piecemeal,” read one internal review in March of Facebook’s response to Stop the Steal groups, which contended that the election was rigged against Mr. Trump. The report’s authors said they hoped the post-mortem could be a guide for how Facebook could “do this better next time.”

Many of the dozens of Facebook documents reviewed by The Times have not been previously reported.Some of the internal reports were initially obtained by Frances Haugen, a former Facebook product manager turned whistle-blower.

Ms. Haugen’s documents, some of which The Wall Street Journal has published, have created an outcry among lawmakers and regulators, plunging Facebook into one of its worst public relations crises in years. The disclosures from Ms. Haugen, who plans to appear at a hearing in Britain’s Parliament on Monday, have resurfaced questions about what role Facebook played in the events leading up to the Jan. 6 Capitol riot.

Yaël Eisenstat, a former Facebook employee who oversaw safety and security on global elections ads, said the company’s research showed it had tried examining its responsibilities around the 2020 election. But “if none of this effects changes,” she said, it was a waste.

“They should be trying to understand if the way they designed the product is the problem,” Ms. Eisenstat said of her former employer.

Andy Stone, a Facebook spokesman, said the company was “proud” of the work it did to protect the 2020 election. He said Facebook worked with law enforcement, rolled out safety measures and closely monitored what was on its platform.

“The measures we did need remained in place well into February, and some, like not recommending new, civic or political groups remain in place to this day,” he said. “The responsibility for the violence that occurred on Jan. 6 lies with those who attacked our Capitol and those who encouraged them.”

A QAnon Journey

For years, Facebook employees warned of the social network’s potential to radicalize users, according to the documents.

In July 2019, a company researcher studying polarization made a startling discovery: A test account she had made for a “conservative mom” in North Carolina received conspiracy theory content recommendations within a week of joining the social network.

The internal research, titled “Carol’s Journey to QAnon,” detailed how the Facebook account for an imaginary woman named Carol Smith had followed pages for Fox News and Sinclair Broadcasting. Within days, Facebook had recommended pages and groups related to QAnon, the conspiracy theory that falsely claimed Mr. Trump was facing down a shadowy cabal of Democratic pedophiles.

By the end of three weeks, Carol Smith’s Facebook account feed had devolved further. It “became a constant flow of misleading, polarizing and low-quality content,” the researcher wrote.

Facebook’s Mr. Stone said of the work: “While this was a study of one hypothetical user, it is a perfect example of research the company does to improve our systems and helped inform our decision to remove QAnon from the platform.”

The researcher, who later ran polarization experiments on a left-leaning test account, left Facebook in August 2020, the same month that the company cracked down on QAnon pages and groups.

In her exit note, which was reviewed by The Times and was previously reported by BuzzFeed News, she said Facebook was “knowingly exposing users to risks of integrity harms” and cited the company’s slowness in acting on QAnon as a reason for her departure.

“We’ve known for over a year now that our recommendation systems can very quickly lead users down the path to conspiracy theories and groups,” the researcher wrote. “In the meantime, the fringe group/set of beliefs has grown to national prominence with QAnon congressional candidates and QAnon hashtags and groups trending in the mainstream.”

Into Election Day

Facebook tried leaving little to chance with the 2020 election.

For months, the company refined emergency measures known as “break glass” plans — such as slowing down the formation of new Facebook groups — in case of a contested result. Facebook also hired tens of thousands of employees to secure the site for the election, consulted with legal and policy experts and expanded partnerships with fact-checking organizations.

In a September 2020 public post, Mr. Zuckerberg wrote that his company had “a responsibility to protect our democracy.” He highlighted a voter registration campaign that Facebook had funded and laid out steps the company had taken — such as removing voter misinformation and blocking political ads — to “reduce the chances of violence and unrest.”

Many measures appeared to help. Election Day came and went without major hitches at Facebook.

But after the vote counts showed a tight race between Mr. Trump and Joseph R. Biden Jr., then the Democratic presidential candidate, Mr. Trump posted in the early hours of Nov. 4 on Facebook and Twitter: “They are trying to STEAL the Election.”

The internal documents show that users had found ways on Facebook to undermine confidence in the vote.

On Nov. 5, one Facebook employee posted a message to an internal online group called “News Feed Feedback.” In his note, he told colleagues that voting misinformation was conspicuous in the comments section of posts. Even worse, the employee said, comments with the most incendiary election misinformation were being amplified to appear at the top of comment threads, spreading inaccurate information.

Then on Nov. 9, a Facebook data scientist told several colleagues in an internal post that the amount of content on the social network casting doubt on the election’s results had spiked. As much as one out of every 50 views on Facebook in the United States, or 10 percent of all views of political material, was of content declaring the vote fraudulent, the researcher wrote.