WASHINGTON — The House voted on Tuesday to remove statues honoring Confederate and other white supremacist leaders from public display at the United States Capitol, renewing an effort to rid the seat of American democracy of symbols of rebellion and racism.

The chamber voted 285 to 120 to approve the legislation, which aims to banish the likenesses of Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, Jefferson Davis and roughly a dozen other figures associated with the Confederacy or white supremacist causes. Sixty-seven Republicans, including the party’s top leader, joined with every Democrat who voted to support the changes, but a majority of the party stood against it.

“We can’t change history, but we can certainly make it clear that which we honor and that which we do not honor,” said Representative Steny H. Hoyer, Democrat of Maryland and the majority leader, who helped write the bill. “Symbols of hate and division have no place in the halls of Congress.”

The legislation will now go to the Senate, where Democrats have vowed to use their new majority to try to advance it but will face off with Republicans opposed to it on ideological and philosophical grounds.

The vote marked the latest round in a yearslong debate on Capitol Hill and across the country over the role of Confederate statuary and symbols in public spaces, and the implications of removing them. Proponents of removing or relocating Confederate monuments and erecting new ones to commemorate the national struggle for equal rights have notched steady progress.

The House and Senate voted overwhelmingly this month to make Juneteenth a federal holiday commemorating the end of slavery. In January, Congress overrode a veto by President Donald J. Trump to enact legislation that would, among other things, direct the military to strip the names of Confederate leaders from bases in the coming years. And inside the Capitol, Speaker Nancy Pelosi ordered portraits of four speakers who served the Confederacy be taken down from the gilded lounge adjacent to the House chamber, where she has control of what artwork is displayed.

The fate of the Capitol statuary has been more complicated, because Congress has no authority over much of it. According to a law that originated during the Civil War, each state may send two statues of deceased citizens who were “illustrious for their historic renown or for distinguished civic or military services,” and whom the state considers “worthy of this national commemoration” to be featured in Statuary Hall, an ornate marble amphitheater-style room just off the House floor, or elsewhere in the Capitol.

The bill passed by the House on Tuesday would direct congressional officials to remove any statue of a Confederate military or government leader, as well as some specific ones, and allow states to send replacements. Many of the statues in question were erected in the early 20th century, when Southern states were romanticizing the “Lost Cause” of the Confederacy and enforcing the segregationist code of Jim Crow.

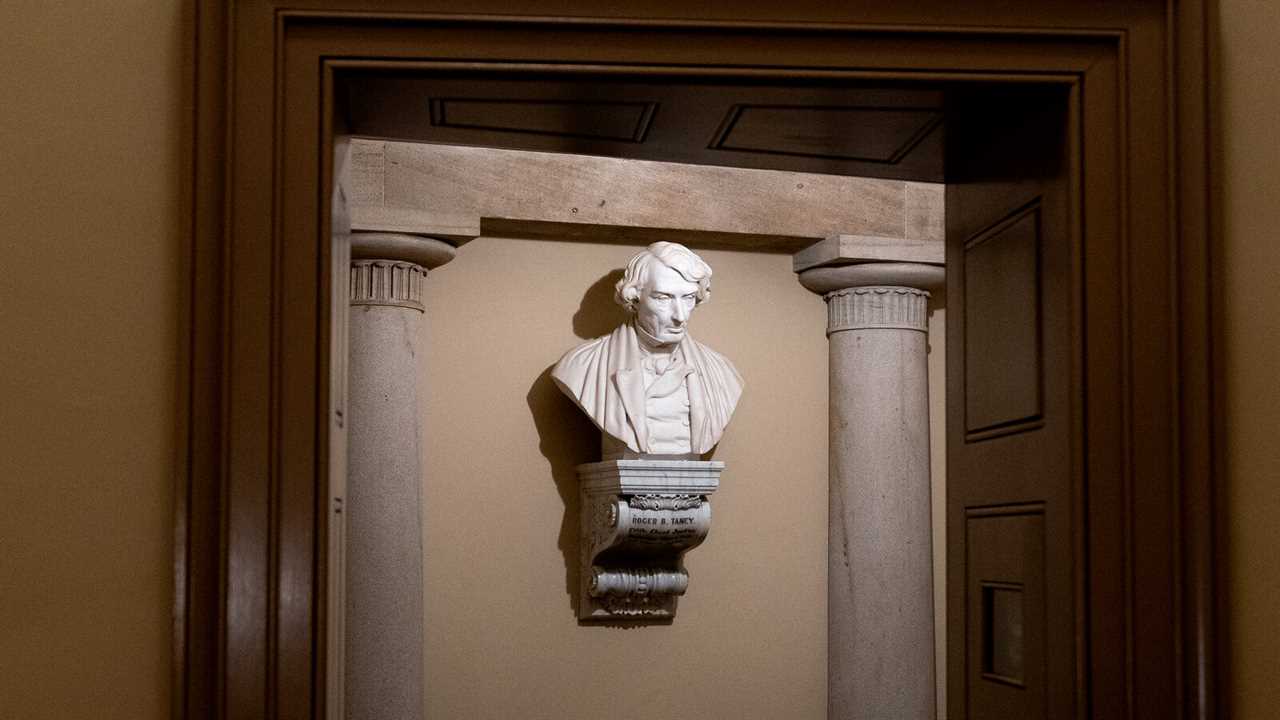

Among them is a bust of Chief Justice Taney, who as the leader of the Supreme Court delivered the landmark Dred Scott v. Sandford decision denying the rights of citizenship to people of African descent. The legislation calls for Taney’s bust to be replaced with one of his fellow Marylander Thurgood Marshall, the first Black Supreme Court justice.

The bill also singles out for removal statues of Jefferson Davis of Mississippi, the president of the Confederate States of America, and John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, the former vice president and leader of the Senate’s pro-slavery faction.

“His contribution to the national discourse was in defense of slavery — that’s why he’s here,” Representative James E. Clyburn of South Carolina, the No. 3 Democrat in the House, said, referring to Calhoun. “Why should we be celebrating a defense of slavery?”

“My message to South Carolina: Come get that statue and put it where it ought to be,” added Mr. Clyburn, the highest-ranking Black lawmaker in Congress. “If you want it here in this Capitol, we’re going to put it in the basement, in a closet somewhere.”

Several states have already voluntarily taken steps to remove and replace some of the statues in question.

Virginia, for example, recalled its statue of Robert E. Lee, the Confederate general, last year and plans to replace it with one of the civil rights leader Barbara Johns. North Carolina leaders have decided to replace the statue of Charles Brantley Aycock, the leader of a violent white supremacist coup in that state, with one of the Rev. Billy Graham. Arkansas and Florida are in the process of making their own replacements.

Conservatives denounced the bill as an attempt to “whitewash” history or deprive states of their ability to choose which figures they want to see honored in the Capitol. Many of the Republican arguments against it on Tuesday, though, focused on complaints about the removal process Democrats had proposed, not their goal.

“It would mean a whole lot more to this body, as well as the American people, if the states who originally put those statues in here were the ones who now ask that they would be removed,” said Representative Barry Loudermilk, Republican of Georgia.

Representative Kevin McCarthy of California, the House Republican leader, voted for removal, but used his comments on the bill to accuse Democrats of promoting racism. He pointed out that many of the statues represented Democrats and had been sent to the Capitol a century before by Democrats, who were then the party most closely associated with Southern segregationists. (The Democratic Party split in the mid-20th century over civil rights, with much of its southern wing decamping to the Republican Party, where it remains, and Black Americans shifting from the G.O.P. to Democrats.)

“They are desperate to pretend their party has progressed from their days of supporting slavery, pushing Jim Crow laws and supporting the KKK,” Mr. McCarthy said. Wielding a what has become one of Republicans’ favorite attack lines, he added that Democrats had replaced “racism of the past” with “the racism of critical race theory,” referring to a framework that explores how the nation’s racist past is still woven into its laws and institutions.

The House overwhelmingly passed the legislation for the first time last summer. But the majority leader in the Senate at the time, Senator Mitch McConnell, Republican of Kentucky, refused to take it up, and Republicans blocked attempts by Democrats to win its approval.

Democrats are hopeful that their control of the Senate may lead to a different outcome. Senator Chuck Schumer of New York, the current majority leader, supports the effort.

Jonathan Weisman contributed reporting.