NEVADA CITY, Calif. — In the Gold Rush, Northern California attracted prospectors looking for financial independence. Now, this area is at the vanguard of a new movement — people seeking to use only the energy they produce themselves.

Angry over blackouts, wildfires caused by utilities and rising electricity bills, a small but growing number of Californians in rural areas and in the suburbs of San Francisco are going off the grid. They can do so because of a stunning drop in the cost of solar panels and batteries over the last decade. Some homeowners who have built new, off-grid homes say they have even saved money because their systems were cheaper than securing a new utility connection.

There have long been free spirits and survivalists who have lived off the grid. But the decline in solar and battery costs and growing frustrations with utilities appear to be laying the groundwork for more people to consider doing so.

Nobody is quite sure how many off-grid homes there are but local officials and real estate agents said there were dozens here in Nevada County, a picturesque part of the Sierra Nevada range between Sacramento and Lake Tahoe. Some energy experts say that millions of people could eventually go off the grid as costs drop. A fully off-grid system in California can run from $35,000 to $100,000, according to installers. At the low end, such systems cost roughly as much as an entry-level Chevrolet Silverado pickup truck.

“It’s not just the doomsayers or the eco-hippies,” said Diane Vukovic, who has researched the laws and regulations about going off the grid for Primal Survivor, an organization that helps consumers with disaster preparedness. “People want to have that self-reliance. It’s become so much cheaper and easier that at this point, there’s very little reason not to do it if you have the means to make the investment now.”

People going off the grid argue that utilities are not moving fast enough to address climate change and are causing other problems. In Northern California, Pacific Gas & Electric’s safety record has alienated many residents. The company’s equipment caused the 2018 Camp Fire, which killed dozens and destroyed the town of Paradise, about 70 miles north of Nevada City. The utility’s effort to prevent fires by cutting off power to homes and businesses has also angered people.

One of those residents is Alan Savage, a real estate agent in Grass Valley, who bought an off-grid home six years ago and has sold hundreds of such properties. He said he never loses power, unlike PG&E customers. “I don’t think I’ll ever go back to being on the grid,” Mr. Savage said.

For people like him, it is not enough to take the approach favored by most homeowners with solar panels and batteries. Those homeowners use their systems to supplement the electricity they get from the grid, provide emergency backup power and sell excess energy to the grid.

auto=webp&

auto=webp&

auto=webp&

auto=webp&

auto=webp&

auto=webp&

The appeal of off-grid homes has grown in part because utilities have become less reliable. As natural disasters linked to climate change have increased, there have been more extended blackouts in California, Texas, Louisiana and other states.

A Critical Year for Electric Vehicles

The popularity of battery-powered cars is soaring worldwide, even as the overall auto market stagnates.

- Going Mainstream: In December, Europeans for the first time bought more electric cars than diesels, once the most popular option.

- Turning Point: Electric vehicles account for a small slice of the market, but in 2022, their march could become unstoppable. Here is why.

- Tesla’s Success: A superior command of technology and its own supply chain allowed the company to bypass an industrywide crisis.

- Rivian’s Troubles: As the electric vehicle maker pares down its delivery targets for 2022, investors worry the company may not live up to its promise.

- Green Fleet: Amazon wants electric vans to make its deliveries. The problem? The auto industry barely produces any of the vehicles yet.

Californians are also upset that electricity rates keep rising and state policymakers have proposed reducing incentives for installing solar panels on homes connected to the grid. Installing off-grid solar and battery systems is expensive, but once the systems are up and running, they typically require modest maintenance and homeowners no longer have an electric bill.

RMI, a research organization formerly known as the Rocky Mountain Institute, has projected that by 2031 most California homeowners will save money by going off the grid as solar and battery costs fall and utility rates increase. That phenomenon will increasingly play out in less sunny regions like the Northeast over the following decades, the group forecasts.

David Hochschild, chairman of the California Energy Commission, a regulatory agency, said the state’s residents tend to be early adopters, noting that even a former governor, Jerry Brown, lives in an off-grid home. But Mr. Hochschild added that he was not convinced that such an approach made sense for most people. “We build 100,000 new homes a year in California, and I would guess 99.99 percent of them are connected to the grid,” he said.

Some energy experts worry that people who are going off the grid could unwittingly hurt efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. That is because the excess electricity that rooftop solar panels produce will no longer reach the grid, where it can replace power from coal or natural gas plants. “We don’t need everybody to cut the cord and go it alone,” said Mark Dyson, senior principal with the carbon-free electricity unit of RMI.

Solar Panels and a View

Pepe Cancino moved from Santa Monica to Nevada County in 2020 after he and his wife, Diane, lost their jobs during the pandemic. They bought five acres with spectacular views of snow-capped mountains. Mr. Cancino, 42, a former home health care worker, picked up a chain saw and an ax and began learning how to build a house and generate his own power.

When they finish their two-bedroom, two-and-a-half-bathroom home this fall, the family, including their 15-year-old daughter, will generate electricity and use a well for water.

“There were a lot of moments,” Mr. Cancino said, “where we were like, ‘This is a lot of work.’” But they are pleased with the results.

Their energy system includes solar panels on two shipping containers, one of which doubles as an office and possible future guesthouse. Another set of panels will sit atop their 2,100-square-foot home. They also have backup propane generators for snowy days.

The Cancinos went off the grid because hooking up to PG&E would have cost more than the $50,000 they spent on solar panels, batteries and generators.

Nevada County was founded in 1851 and stretches almost a thousand square miles with peaks as high as 5,000 feet above sea level. Black bears roam freely and a single snowfall can blanket the ground with three feet of powder.

Though the county leans liberal, interest in off-grid living bridges the partisan divide. Solar and batteries offer the self-reliance conservatives crave and the environmental benefits progressives seek.

But Scott Aaronson, a senior vice president for security and preparedness at the Edison Electric Institute, a utility industry trade group, said that while off-grid living might appeal to some, it was “like having a computer not connected to the internet.”

“You’re getting some value but you’re not part of a greater whole,” he said. “When something goes wrong, that’s wholly on you.”

Some homeowners have lived without a grid connection for years but interest in cutting the cord surged after PG&E began to frequently use power shut-offs as a fire prevention tool in 2019, said Craig Griesbach, director of the Nevada County building department.

The county last year published a document to help homeowners go off the grid while complying with building codes. Mr. Griesbach said officials from as far as Los Angeles had contacted his office for advice on off-grid rules.

“Fifteen or 20 years ago, you wouldn’t have been able to do this,” he said.

PG&E said homeowners in rural areas like Nevada County had always been more likely to go off the grid because extending power lines over long distances simply costs more.

Falling Costs and Better Technology

A decade or two back, off-grid homes included a patchwork of solar panels, diesel or propane generators and lead acid batteries. A system that could run a furnace, a refrigerator and washer and dryer could cost well over $100,000.

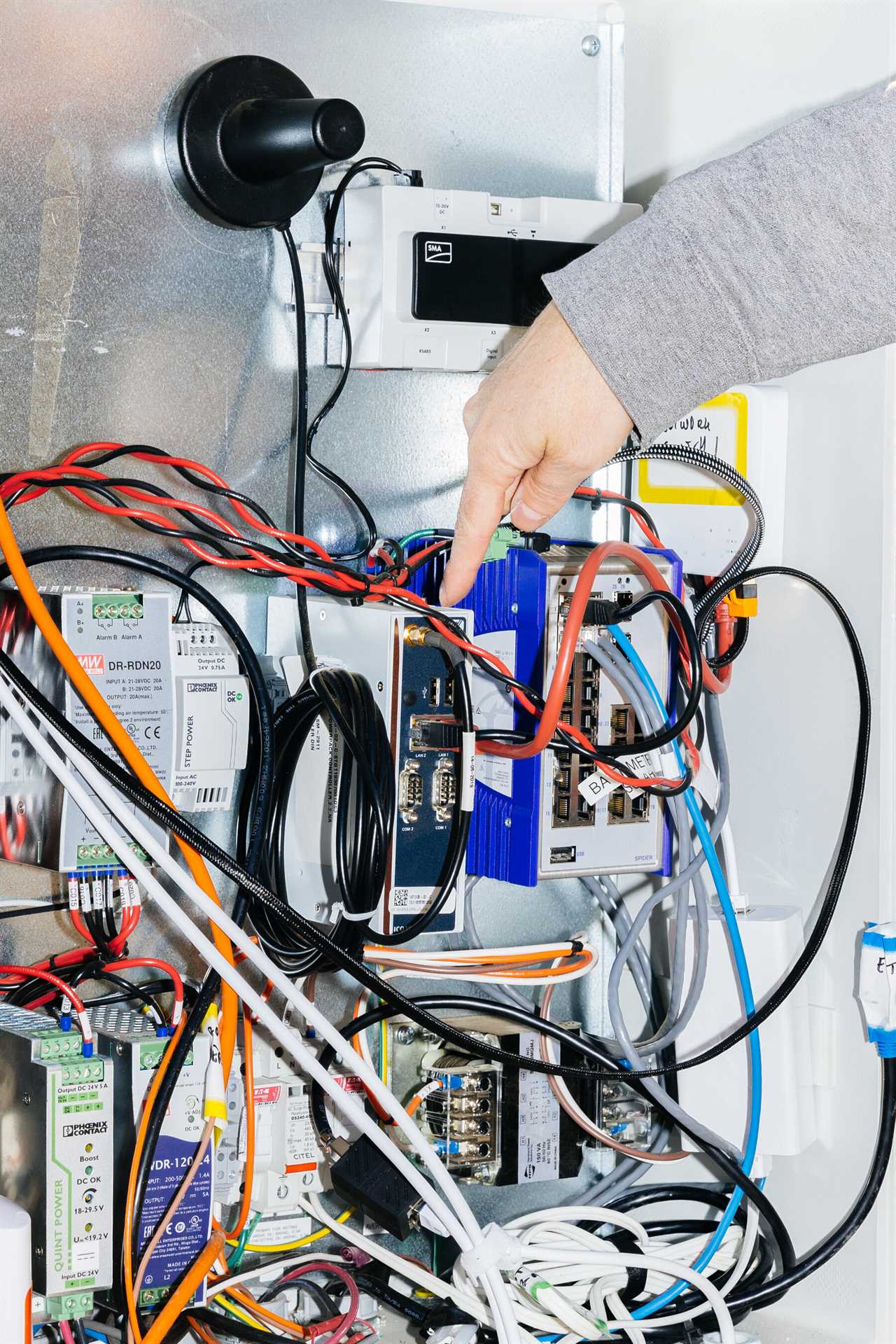

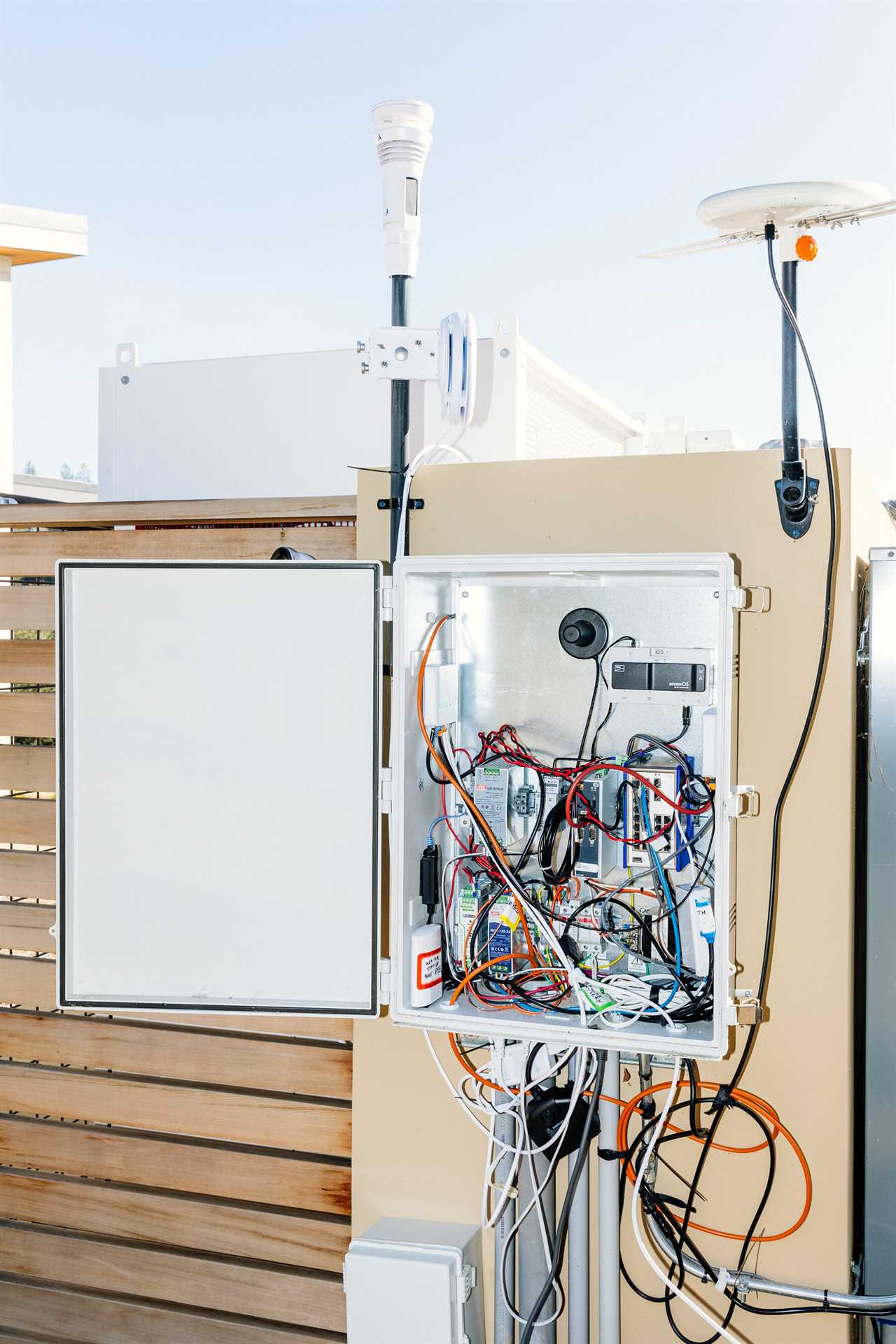

Most current off-grid systems rely heavily on solar panels because their cost has fallen to less than 4 cents a watt from about 11.4 cents a watt in 2000, not including state and federal incentives, according the California Solar and Storage Association. Lithium-ion batteries weighing as little as 30 pounds, requiring minimal maintenance and costing $10,000 to $20,000 have replaced banks of lead acid batteries that used to cost tens of thousands of dollars, could weigh thousands of pounds and needed regular upkeep. Generators are often used but serve mostly as an emergency backup, as they do for homes connected to the grid, said Aaron Schroeder, who installed the systems used by the Cancinos.

Off-grid systems are particularly attractive to people building new homes. That’s because installing a 125- to 300-foot overhead power line to a new home costs about $20,000, according to the California Public Utilities Commission. In places where lines have to be buried, installation runs about $78,000 for 100 feet.

That’s why Wim Coekaerts went off the grid in his 2,800-square-foot home in Woodside, near Stanford University.

His plot sits just across the street from homes that are connected to PG&E. But the utility told him it would cost $100,000 for new electric service, and building a trench for the line, based on regulatory estimates, could add $300,000 or more. So he spent $300,000 after federal tax credits on solar panels and a large battery.

After a year of living in the house, Mr. Coekaerts, an executive at Oracle, is happy with his choice. While his neighbors on PG&E have lost power three times, he said, he hasn’t gone without it “even for a nanosecond.”

auto=webp&

auto=webp&

auto=webp&

auto=webp&

auto=webp&

auto=webp&

“When it was really bad weather the first time, I was nervous,” said Mr. Coekaerts, a native of Belgium who moved to the United States in 1997. “Now I feel comfortable.”

He has never had to ration his use of appliances and has had no problems charging two Teslas. He has been producing so much electricity that he started mining Bitcoin.

His system cost a lot because he bought a very large battery to soak up energy from solar panels for use when the sun isn’t shining. But electric cars may soon play that role, making it cheaper to go off the grid.

Electric cars available now aren’t designed to send power to homes. But newer models like the Ford F-150 Lightning and the Hyundai Ioniq 5 will have that ability, said Bill Powers, a San Diego engineer who plans to go off the grid with the help of an electric car. “The Holy Grail to me now is in electric vehicles.”

Did you miss our previous article...

https://trendinginthenews.com/usa-politics/finding-a-way-out-of-the-war-in-ukraine-proves-elusive