The statement announcing the latest raft of presidential pardons was officially attributed to the White House press secretary, but it bristled with President Trump’s own deep-seated grievances.

His friend and longtime adviser Roger J. Stone Jr., the statement said, “was treated very unfairly” by prosecutors. His former campaign chairman Paul Manafort “is one of the most prominent victims of what has been revealed to be perhaps the greatest witch hunt in American history.”

In complaining about “prosecutorial misconduct,” though, Mr. Trump seemed to be talking as much about himself as his allies. In the flurry of 46 pardons and commutations issued this week, he granted clemency to a host of convicted liars, crooked politicians and child-killing war criminals, but the through line was a president who considers himself a victim of law enforcement and was using his power to strike back.

Never mind that Mr. Trump presents himself as a champion of “law and order.” He has been at war with the criminal justice system, at least when it has come to himself and his friends. And so in these final days in office, he is using the one all-but-absolute power vested in the presidency to rewrite the reality of his tenure by trying to discredit investigations into him and his compatriots and even absolving others he seems to identify with because of his own encounters with the authorities.

In some ways, of course, this is the concession that Mr. Trump has otherwise refused to issue, an unspoken acknowledgment that he really did lose the Nov. 3 election. These are the kinds of clemency actions a president would take only shortly before leaving office.

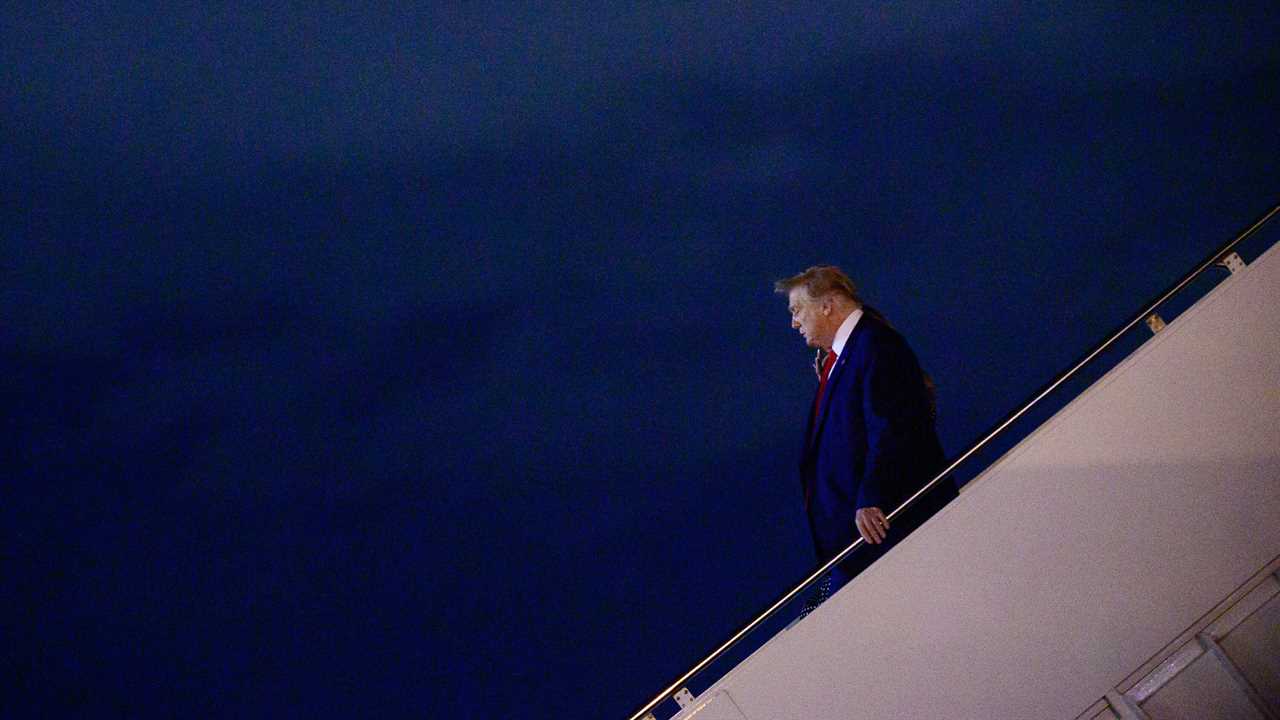

But it also represents a final, angry exertion of power by a president who is losing his ability to shape events with each passing day, a statement of relevance even as Mr. Trump confronts the end of his dominance over the nation’s capital.

In the seven weeks since the election, he has screamed over and over that he actually won only to be dismissed by essentially every court and election authority that has considered his false assertions, which were also rejected by his own attorney general.

He demanded that Congress rewrite the annual military spending bill to preserve the names of bases honoring Confederate generals only to have both parties ignore him and pass the measure overwhelmingly, setting up the first veto override of his presidency.

He likewise is trying to belatedly make himself a player in the coronavirus relief package he all but ignored until after it had already passed both houses on large bipartisan votes with the support of his own administration and Republican leaders. In doing so, he demonstrated that he could still cause chaos in the last stretch of his tenure at the expense of Americans who may now go without aid this Christmas season, even if it was unclear that he would be able to impose his will on the final outcome.

As power inexorably slips from his grasp, the defeated president finds his pardon authority to be the one weapon he can deploy without any checks. It is the most kingly of powers conferred on a president by the Constitution, one that is entirely up to his discretion, requires no confirmation by Congress or the courts and cannot be overturned.

Other presidents have been criticized for using it for political allies, particularly George Bush, who spared a half-dozen colleagues in the Iran-contra investigation, and Bill Clinton, who granted clemency to his own half brother, a former business partner and the former husband of a major donor.

But few if any have used their pardon power to attack the system in quite the way Mr. Trump has.

Under Justice Department guidelines, pardons are normally not even considered until five years after an applicant completes a sentence and are “granted in recognition of the applicant’s acceptance of responsibility for the crime and established good conduct.”

But a president does not have to follow those guidelines, and Mr. Trump, famously dismissive or ignorant of norms, has largely dispensed with the Justice Department process for vetting clemency requests, treating them in many cases not as acts of forgiveness but assertions of vindication.

In addition to Mr. Stone and Mr. Manafort, the president this week pardoned three other figures convicted of lying in the Russia investigation led by the special counsel Robert S. Mueller III. They came on top of a similar pardon last month for Michael T. Flynn, Mr. Trump’s national security adviser, and were all part of a broader effort to erase what he has called a “hoax” inquiry.

Critics accused Mr. Trump of using his power to obstruct justice by rewarding allies who impeded the investigation against him. “The pardons from this President are what you would expect to get if you gave the pardon power to a mob boss,” Andrew Weissmann, a top lieutenant to Mr. Mueller, wrote on Twitter.

Some framers of the Constitution worried about just such a scenario. George Mason argued that a president “ought not to have the power of pardoning, because he may frequently pardon crimes which were advised by himself.”

Mr. Trump’s critics have suggested his pardons could be tantamount to obstruction of justice, noting that Mr. Trump regularly dangled the prospect of pardons at the same time Mr. Manafort, for example, was being pressured to cooperate with investigators.

At the confirmation hearing in 2019 for William P. Barr, whose last day as attorney general was Wednesday, Senator Patrick J. Leahy, Democrat of Vermont, quizzed him about that. “Do you believe a president could lawfully issue a pardon in exchange for the recipient’s promise to not incriminate him?” Mr. Leahy asked.

“No,” Mr. Barr replied. “That would be a crime.”

Some Democrats have sought to restrain Mr. Trump’s pardon power. Representative Steve Cohen of Tennessee introduced legislation last year to prohibit the president from pardoning himself, his family, members of his administration or campaign employees. Senator Christopher S. Murphy of Connecticut even called for removing the pardon power from the Constitution.

In a new book, Robert F. Bauer, a former White House counsel to President Barack Obama and a top adviser to President-elect Joseph R. Biden Jr., and Jack L. Goldsmith, a former senior Justice Department lawyer in President George W. Bush’s administration, proposed amending the bribery statute to make it illegal to use pardons to bribe witnesses or obstruct justice.